Eells

Note: Sadly, John Eells has passed away. Linwood Hines, longtime friend of John and fellow member of the Conclave of Richmond Pipe Smokers (CORPS) wrote a beautiful tribute in the August edition of the The Pipe Collector, as did Rich Esserman. John will be greatly missed by his family and friends, and all of us who knew him. Thankfully he leaves a tremendous legacy in the pipes he made, helping and inspiring other pipemakers, and in the pipe community over all--he lives on through all of us.

John Eells is cited as an early mentor in the vast majority of American pipe maker bios. His pipes are excellent, and his passion and dedication to pipe making have served as the inspiration for the many amazing pipe makers he has helped to train and inspire!

The following article originally appeared in the Profiles of American Pipes Makers series in the Februray 2004 issue of The Pipe Collector, the official newsletter of the American Society of Pipe Collectors (NASPC), and is used by permission. It's a great organization--consider joining.

Profiles of American Pipe Makers: John H. Eells

John Eells' childhood home was Walton, NY, a small town in Delaware County. When John was a young boy in the 40s and 50s, most of his adult relatives were pipe smokers. His father, a tool and die maker by trade, had a nice collection that included a couple of Barlings and a few very fine Patent Dunhills. His grandfathers, a great uncle, and an uncle also enjoyed pipe smoking. On the street and in local factories, John often saw men with pipes dangling from their lips. Many respected actors, singers, and public figures of that period smoked a pipe. So it is understandable how, during these impressionable years, John came to believe that the gentile art of pipe smoking distinguished a man of high intellect and respectability.

From very early on, John had a strong fascination with mechanical devices. Working with his hands, and tinkering with anything mechanical was almost an obsession. Anything that was broken or didn't work was taken apart if John could get his hands on it. Eventually he was able to analyze what was wrong and to make simple repairs. By the are of 12, he was capable of disassembling, cleaning and reassembling watches as well as making minor repairs. During this time, he developed his patience and the rudiments of his hand dexterity.

In 1958, John's family relocated to Charlottesville, VA. At age 16, John found part-time work after school, on weekends, and during the summers repairing watches at a local jewelry store. He continued with his watch repairs while studying at UVA from 1961 to 1963 before entering military service.

During those fist few years in Charlottesville, John discovered Mincer's Pipe Shop on "The Corner" across from the UVA Campus. While attending UVA, he was fortunate to enjoy an occasional pleasant and informative conversation with Robert Mincer, found and proprietor of the shop. Mincer was a master pipe maker and, although it is not commonly know, he was also the brother ot Tracy Mincer, founder of Custom-Bilt pipes. Robert was a key player in the Custom-Bilt story in the years before the name was sold to Rogers. In the mid 1940s, Robert Mincer moved to Charlottesville and opened his own shop. In 1961, at age 18, John purchased his first good-quality pipe from Mincer--a small full-bent Comoy Tradition that Mincer personally chose for him. Thus began a pipe-smoking hobby that has been "a lifelong source of enjoyment" for John.

After two years in college, John took a leave of absence from school and enlisted in the Army of three years. "Yes, I took my pipes." After completing his tour of duty in October, 1966, John returned to Charlottesville and worked a couple of years in the Engineering Dept. of Sperry Marine Systems as an engineering assistant while he attended classes at UVA on a part-time basis. In the experimental shop at Sperry, he picked up some of his machinist's skills. In 1968, John decided to return to UVA and complete the requirements for a S.S.M.E. degree. Continuing to work full-time at Sperry was impractical, and, since Robert Mincer's shop was practically on campus, John approached him for a part-time job clerking in the shop. Mincer was well known for lending a helping hand to students in need of work. Jon says that Mincer, who no longer involved himself in the repair end of the business, asked if John would like to try his hand at pipe repairing, and of course, the answer was yes. After checking John out for an hour or so, Mincer offered him the job. John elates that Mincer actually trusted him with a key to the shop so that he could work whenever he was free, day or night. All he had to do was stay caught up with the work.

During the next several years, under Mincer's careful guidance, John acquired experience repairing and carving pipes. John also began to establish a modest collection of pipes because, as well as offering a store discount, Mincer allowed him to purchase any unclaimed pipes for the repair cost. Many opportunities to acquire fine pipes occurred because, whenever someone left his pipe for repair and left school or otherwise failed to pick it up, John had first right of refusal to purchase it for the repair cost. John points out that this system showed the wisdom and business sense of the old master, who subtly incorporated an effective quality control incentive. " You are going to take good care of something that could be yours someday." So now pipe making, repairing and collecting were added to John's pipe-smoking hobby.

In 1972, after graduating, John went to work for Phillip Morris in Richmond, VA., where he was fortunate to learn a good deal about pipe tobaccos from the master blenders at the 17th and Dock Street location. At that time, Phillip Morris was one of the nation's largest pipe tobacco manufacturers. Not only did PM manufacture their own labels and ship bulk tobaccos to tobacconists all over the country, but it also blended and packaged for many other companies, Dunhill included. At Phillp Morris, John was able to continue developing shop skills because most of his career was spent working closely with maintenance personnel. He had the good fortune to have access to the machine shops and permission to sue the equipment. John was even lucky enough to supervise the machine shope at one location for several years.

During the 26 years John worked for Phillip Morris, he continued to pursue those activities that could be defined more accurately as hobbies, except that they provided additional income.. At one point, he owned a gift/card shop that provided watch and clock repair services. During the same period, he was repairing watches for three retail jewelers and five pawnbrokers. At times, when John's schedule wasn't so intense, he found time for building his pipe collection, refurbishing pipes, and even making a few pipes.

Over the past 30 years in Richmond, John's interest in making pipes has grown. He freely admits that he probably would not have continued working in the craft if it hadn't been for the support and encouragement of many pipe-loving friends and associates and the establishment of the internationally recognized Conclave of Richmond Pipe Smokers. John believes that the lion's hare of credit goes to Linwood Hines. "The C.O.R.P.S. was Linwood's dream first. He was the catalyst that brought us all together in the beginning. The establishment of the anual C.O.R.P.S. Pipe Expo has led to friendships with pipe collectors and carvers. Over the years, many other pipe clubs have formed, some of which are also sponsoring events. Attending these events has further increased the number of great pipe enthusiasts on my list of cherished friends. Thanks, Linwood."

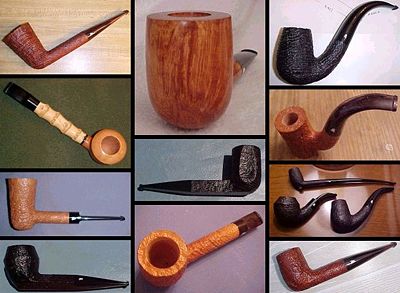

Since the Mincer years, John has continued making and restoring pipes. Now retired, he is endeavoring to spend even more time making hem. According to John, "My pipes are typically made in the Standard English shapes; however, I do invite custom work. A lot of my pipes are larger than the norm, but I also make smaller sizes, including pipes for the ladies." All of John's pipes, including moutpieces, are constructed of the highest quality materials and are entirely (every inch) hand made.

Nomenclature

John uses a combination of stamping and machine engraving on his pipes. On his first-quality pipes, the John H. Eells line, "EELLS U.S.A." and "JH Eells" (a script signature) are stamped on the shanks of the pipes. Engraved on the shanks with a Hermes pantographic engraver are the size, date, and shape information that I discuss below. On the stems of these pipes, John engraves his "J H Eells" signature and fills it in with white enamel. Because the signature is actually engraved into the stem approximately 1/32 of an inch, using a cutter that tapers to a point, it will not "pop out", as occasionally happens with stems that are stamped with a heated die. For this reason, subsequent buffing will make the signature become sharper. On John's Poplar Ridge line (which is described later), John engraves "Poplar Ridge" and stamps his "JH Eells" signature into the shank. On the stem, he engraves the letters "PRSP" (which stand for Poplar Ridge Smoking Pipes), using he same process as on his regular John H. Eells line. The Poplar Ridges line includes no shape, date, or size information, nor does it include the "EELLS" U.S.A. stamp. John also stamps his first-line pipes with a number, followed by a space, followed by three letters, followed by a spcae, followed by another letter and an optional asterisk, such as "2 DCU H*."

The number indicates the size of the pipe and signifies nothing abut grade. John's group 1 pipes can range up to about a group3 size of other makers. His group 2 pipes range from a group 4 to a group 6 of other makers. A group 3 starts at group 6 size and ranges up to a group 4 to a group 6 of other makers. A group 3 starts at group 6 and ranges up to a larger than ODA but still smaller than a magnum. A group 4runs in the range starting a bit smaller than a Magnum. The larges pipe John has made thus far is a group 14, which was over a foot long and had a bowl over 4 inches tall.

The first letter stand for the year, starting in 1998 with "A," so "F" would 2003.

The next two letters designate the pipe and stem shapes. "CU" indicates a standard billiard with a tapered stem. At this time, John has over 80 shapes, and the number is growing constantly.

The final letter indicates the pipe's finish. "H" designates a black sandblast with red highlights similar to the older Dunhill Shells. he letters John uses to indicate his finishes will also appear on his web site when it is finished.

On some Eells' pipes, there is an asterisk (*) or other symbol following the finish code. This symble indicates that the pipe was originally fitted with a stem made of material different than black vulcanite. Typically, all standard Eells' pipes come with a black vulcanite stem. Therefore, there is no additional designation following the finish code on these standard pipes having black vulcanite stems. If you should come across a pipe with stampings not consistent with the finish or stem material, then the pipe has been modified in some way from the original. An example would be a pipe with a Cumberland or Brindle stem having no stem designation. his would man that the pipe originally had a black vulcanite stem but that the stem has been replaced with the different material.

Philosophy

John's pipe-making philosophy is pretty. 1) Use the finest materials available. 2) Eahcn pipe must be designed to function properly. 3) A pipe should be pleasing to the eye and touch. 4) Never rush the process.

Materials

Substandard materials are unlikely to yield a quality pipe, so John uses the finest briar available. This doesn't guarantee a flawless grain or a sweet smoke, but it improves the odds. "With occasional exceptions, we generally get what we pay for," John believes. Stems can be made from many different materials, but John's focus is that it be tough, lightweight, attractive, and not give off any dangerous or unpleasant fumes when heated. However, as John says, "I am somewhat old-fashioned and traditional and prefer the look and feel of vulcanite."

Making The Pipe Work

According to John, a pipe must be designed and constructed to function properly. It should provide a dry, comfortable, unencumbered smoke. The draft hole must allow for an easy draw, and it should meet the tobacco chamber correctly at the bottom. The tobacco chamber should not be too large or too small, and it should be designed so that it will be right when a cake of 1/16 to 1/8 inches has built up on the wall. The feel of the mouthpiece should be comfortable and adequate for the pipe's size and weight. The bowl should be thick enough that it won't be a candidate for overheating and burnout or distortion and cracking due to exposure to combined heat and moisture. "Pay attention to those little details that may not seem too important," John says, "because they really are. Getting the plumbing right is very important. It doesn't matter how beautiful a pipe is if it burns out or cracks or if your customer gets a hernia trying to puff on it. Remember that a draft hole that hits the tobacco chamber 1/8" off to one side or 1/4" too high can cause big problems in the future."

Aesthetics

According to John, once a pipe maker is able to successfully accomplish the tasks critical to the proper function of a pipe, he or she should focus on incorporating them by constructing the pipe's exterior so that it will be pleasing to the eye and touch. Study the wood and decide what shape to make, carefully considering the orientation of the grain and where to locate the tobacco chamber and draft hole. "It's the process of combining the engineering with the art." Because there are so many beautiful freehand pipes and innovative shapes appearing every day, it is difficult to know what shape or style will be pleasing to one person and not to another. However, according to John, "It is a fact that bad quality is never esthetically pleasing and can be maddening for the customer who discovers it after laying down a sizable chunk of change."

Many features will reveal quality workmanship or the lack thereof. Examples include the following. If the bowl is round, the tobacco hole should be concentric with the outside of the bowl. If the bowl is intentionally irregular, then the tobacco chamber should be located such that there aren't any spots where the wall is too thin. The mortise should be in the center of the shank so that there are no weak or thin areas that might crack or split under the pressure of a tightly-fitted tenon. On pipes with round or symmetrical shanks, such as oval, diamond, or square, one should be able to rotate or "flip" the stem 180 degrees with little evidence of misalignment. This is a clear measure of the degree of care the pipe maker used in this critical area. (Obviously, sandblasts can be off a little bit, but usually a person can tell if the pipe was correct before blasting.) The outside finish of a smooth pipe should not be irregular, with little humps or flattened-out areas. If there are flaws in the work such that trying to work around them would cause the surface to become irregular, perhaps the pipe should be rusticated or blasted. If the pipe design is symmetrical, then the pipe should be so. If the pipe's finish is smooth or textured in some way, it should still show quality and careful workmanship in the finishing process. Be aware that your customers are going to live with the pipe you made for years, John emphasizes. "Eventually they will look at every little detail. Make sure that, in the years of close scrutiny, nothing will disappoint them."

John says it would be easy to go on and on with more examples of what to look for in a quality hand-made pipe, but he'll stop here with some general advice for pipe smokers. "Educate yourselves very carefully. Learn what is good and what is bad because it isn't necessarily true that a beautiful pipe will yield a great smoke and not have hidden flaws. Always remember that poor quality can be hidden or disguised." John says that he really wants to emphasize this point: "Don't be fooled by a great-looking pipe without very careful examination because there are people out there who are very talented at disguising/hiding imperfections. And they are selling those pipes at very high prices."

Don't Hurry The Process

John believes that the amount of time you spend making an individual pipe shouldn't enter into your thinking. It should not be in an artist's nature to rush the process. "If we hurry, we lose focus on quality. This can lead to cutting corners and producing substandard products. In the end, our reputation will suffer, and our work will not be in demand."

Many people have asked John how long it takes him to make a pipe. He is retired now and out of the rat race, where success is based on how many units are produced per hour and what the production cost per unit is. In his present situation, time doesn't really matter that much. What does matter is that each pipe he makes is the best it can be and that no act on his part should limit its potential. "If it takes a little longer to get it there, it just means a few more pleasant hours of relaxation in the shop." It does matter that each pipe is fairly priced based on its own merit and that whoever purchases it is confident that they got good value for their money. It matters that each pipe finds its way into the hands of someone to whom it will bring as much pleasure smoking it as John had making it. It matters that it will be more than just a tool to burn tobacco. John's hope is that every owner of one of his pipes will testify that it is the sweetest pipe they ever owned. "Maybe they will pause from time to time to savor the look and feel of it and send an occasional pleasant thought my way."

Poplar Ridge Pipes

John notes that, in fairness to himself and other pipe makers, it is important to make the point that sometimes, even though they strive to make perfect pipes, things happen that cause some of them to be less than a first-quality piece. If such flaws or mistakes will not adversely affect a pipe's smoking or usable life, destroying it would be a shame. Examples can include fissures, sand pits, poor grain, small hairline cracks, or minor misalignment in the drilling and boring. These things will happen and, for the most part, are outside the pipe maker's control due to the fact that briar is a naturally grown substance that will often have flaws. Sometimes a soft spot in the work will guide a flexible drill bit a tiny bit "off."

For this reason, from time to time, John will be making some of these pipes available under the name "Poplar Ridge" Pipes by J.H. Eells." Some of these pipes will have hand-cut stems, while others will have molded stems, the choice being determined by how far along john is in the process when he makes his decision. These pipes are made of the same quality brier that he uses to make all his pipes and will have the same smoking characteristics as his first line. John intends to offer these pipes at reduced prices in natural finishes so that potential buyers will be able to see exactly what they are paying for and will acquire good value relative to the cost. If a buyer wants one of these pipes finished out, John will be happy to do so. That is, John's intention is to make Poplar Ridge pipes available "au naturel," with no stain or finish. However, he does honor requests to stain and polish them.

The John Eells Giant by Ardor

The idea that we had to do a John Eels profile actually hit me when I saw the Monjure international ad in Pipes & Tobaccos that introduced "The John Eells Giant." As Steve Monjure wrote, "We are very proud to honor this great man and master [pipe makers who is responsible for the creation of the Ardor Giant Series. This wonderful shape, designed by John, is a special pipe' named after a 'special man'. Here's how John explains how this all came about. [Ed] Here is how this thing got started. About six years ago at a show, I saw some of the Ardor pipes in the light Meteora finish on Steve's table. This new finish really caught my eye. After some discussion, I purchased one and was very pleasantly surprised by the feel and incredibly sweet taste and aroma of the pipe. (I add that it was a surprise because I had a disappointing experience with a three-pipe Detective set made by Ardor I had purchased back in the 80s. In no way are my remarks directed at the fine craftsmanship in the creation of these pieces. All three pipes were beautiful, and they were splendid examples of the pipe-maker's craft. Unfortunately, however, they all were quite bitter and bit the heck out of my tongue. I worked hard with them, but in the end they just didn't make the grade.)

Because the experience of this new-found pie was so pleasurable, I made a special request of Steve to have one made for me in the same shape, only larger. Well, when I got it, it was another pipe the likes of which dreams are made. The I got carried away and requested an even larger one of the same shape, and it too was fantastic. Since then, I have kept these pipes close, and , although they are not for sale, I have made a special point to have them visible on my tables at shows. When inquiries were made about them, I always sent or escorted the people to Steve's display.

Somewhere in this whole sequence of events, Steve and I had a discussion about pipe size. I like a big pipe. That's not to say I want them to be as large as what "Esserman, Robinson and Morrison" are accustomed to, but I do like them a little larger than the norm. Anyway, somewhere in this dialog (which is probably better described as a mingling of words and thoughts over time) between Steve and myself, he decided to request his carvers to send him some larger pieces in some of the already "tried and true" shapes as well as some new designs to see how thy would sell. From what I've seen and heard, it turned out to be very successful. I was delighted to see it happening because I like Steve and the support he gives the industry. He is truly one of the "Good Guys." Now, somewhere in the midst of all these goings on, Steve asked me if they could make a shape similar to a large billiard that is one of the most requested shapes I make and if they could put my name on it. I should make it clear that my rendition (of a shape that has been around for many years before I was born) is certainly not a design I can take credit for. Anyway, I agreed.

Honestly, I am flattered to have been given so much credit for pushing Steve into the "Big Pipe" arena, and I am grateful that he had such nice things to say in the Ardor ad. Also, I must confess that I really like the way he tells it a lot better than my recollection of events, but I must truthfully say that I really don't deserve that much. Everyone who knows Steve will agree that this kind of thing is in his nature. I am proud and honored that he considers me a friend.

Contact information

John Eells 11513 Poplar Ridge Rd. Richmond, VA 23236-2423, USA +1 804-794-3173 E-mail: mailto:johneells1@comcast.net