Who Carved the First Briar Pipe?

Jean-Christophe BIENFAIT

When we look at the history of the briar pipe, there is one question we inevitably ask ourselves: who first had the idea of using briar for pipes, and when?

As is often the case, there are several candidates for invention, and several stories have been told over time. And it seemed interesting to me to study how these variants came about, and at what period. So I took the documentation at my disposal and I tried to list these different variants and their appearance. Of course, if anyone has older data to complete this, I'm interested.

But let's start: The first person to offer a history of this discovery was Alfred Dunhill, in a book written in 1924, The Pipe Book, the earliest work on the pipe that I have (and one of the most famous).

So, what does Alfred tell us? He suggests what could be called the "Corsican Hypothesis":

"... The discovery of the ideal pipe material, the so-called briar root, was quite accidental, as such discoveries so often are.

It was incidental to the revival of the cult of the great Napoleon, in the second decade following his death in 1821, when the disasters of 1814 were forgotten. Those who wished to honor their late Emperor were not content to visit the tomb at the Invalides, whither his ashes had been brought from St Helena, but made a pilgrimage also to the birthplace of the Little Corporal in Corsica.

Among these pilgrims was a French pipe maker, who during his stay had the misfortune to break or lose his meershaum pipe. He commisionned a Corsican peasant to carve him another, and this was done, the pipe proving such a success that its possessor secured a specimen of the wood from which it was made and brought it home with him. This wood, noted locally for its hardness and fine grain, was the root of the tree-heath, or bruyère, to give it its French name, and from this date, somewhere in the early fifties, it was destined to supersede all other pipe materials. The specimen roots which the French pipe maker brought away from Corsica were sent by him to a factory at St Claude from which he accustomed to buy wooden pipe-stems, where i t was turned into bowls and thus one more was added to the already far-famed articles de St Claude ..." [1]

Then, in 1927, a French geographer, botanist and explorer, Auguste Chevalier, founder in 1921 of the Revue de Botanique Appliquée et d'Agriculture Coloniale, published in this same journal an article entitled: "Note sur l'Erica Arborea et sur l'emploi de ses souches dans la fabrication des pipes" (Note on Erica Arborea and the use of its strains in the manufacture of pipes).

Very interesting article in which he declares among other things: "... According to Mr. V. Davin, honorary sub-director of the Botanical Garden of Marseille, the industry of the pipe in root of Bruyère took birth around 1850 in Saint-Paul-de-Fenouillet in the Eastern Pyrenees ..." [2] (note that he does not take this information to his account).

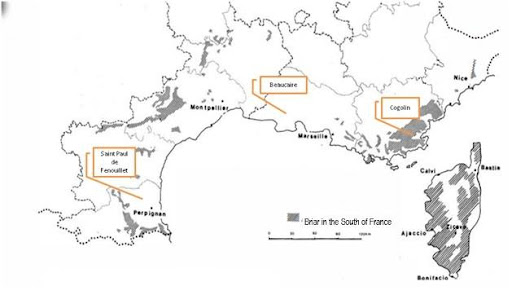

Saint Paul de Fenouillet is close to Perpignan to locate it (see below in the article the map of the implantation of the heather in the south of France). This village had many wood turners in the 19th century.

At about the same time, in 1929, another French geographer, André Mathieu, published an article in the Annales de Géographie entitled "Les Petites Industries de la Montagne dans le Jura Français" (Small Mountain Industries in the French Jura). He said that "A turner, returning from the Beaucaire fair in 1854, had the idea of using the briar root for the manufacture of the pipe. The new material, very hard, gave all satisfaction, and the industry took a remarkable rise ..." [3]

Almost ten years later, in 1937, another French geographer (and long live the geographers!) Thérèse Colin published an article entitled "Les industries de Saint-Claude" (Saint-Claude's industries) in the journal Géocarrefour (founded in 1926, Géocarrefour - formerly Etudes Rhodaniennes and Revue de Géographie de Lyon - is one of the oldest French-speaking geography magazines).

She says in particular that "... A happy chance brought the ideal material: a San Claudian (inhabitant of Saint-Claude) met in 1854 in Beaucaire, where he had gone to sell his products, a merchant of the South who advised him to try the heather. This shrub Arborica Scoparia (NB it is an error of T. Colin, who had confused the Erica Arborea or pipe heather, with the Arborica Scoparia or broom heather - This error will be pointed out to the magazine a little later by the Director of the Ecole des Eaux et Forêts of Nancy, whose letter the magazine will publish) is special to the Mediterranean flora and should not be confused with the Brittany heather. It has a height of 3 to 4 meters and forms a stump at ground level, a kind of onion of 60 to 80 centimeters in diameter weighing up to 50 kilos. These are the stumps that are used for the pipe's hearth. They must be at least thirty years old. The beautiful pipes come from hundred-year-old briars. The countries producing briar are Provence, Corsica, Sardinia, Algeria, Morocco, Spain, Italy, Albania, Greece ...". [4]

After the War, a Frenchman, Georges Herment, published in 1952 the Treaty of the Pipe. He wrote:

"... It is in the Eastern Pyrenees that the best roots and the most voluminous ebauchons are found. But - although there is also an industry in Paris - it is Saint-Claude, in the Jura, which holds the speciality of the manufacture of the pipes in root of heather ...". [5]

He adds later in an note:

"In truth, it is Cogolin, in the Var, which is the "ethnological" capital of the briar root pipe. Cogolin, in its two factories, groups almost all the roots of the Mediterranean basin. During the war, the root being subject to quotas, like all other products, Saint-Claude exchanged ebonite, which Cogolin lacked for its pipes, for ebauchons or cubes. One can only say that the manufacture of Saint-Claude is more careful, more meticulous - and the presentation more luxurious. Saint-Claude remains, despite Cogolin, the official capital of LA PIPE ..." [5]

In 1954, Alfred Henry Dunhill, the son of the company's founder, published a book entitled "The Gentle Art of Smoking". Here, he states, among other things, that:

"... We may well guess what pipes we might have to-day were it not from the french pipe manufacturer who, on a visit to Napoleon birthplace, is alleged to have broken his meerschaum and to have ordered a Corsican paesant to copy it in the local briar. Doubtless someone else would have discovered this valuable material. As it was, the first specimen of briar were sent to St Claude, a remote village high in the Jura mountains, where the villagers, following the example of the monks, had established a thriving wood-carving industry. From that day they turn their attention from work in the local box-wood to the manufacture of "La Pipe" ...". [6]

In these lines he takes up the theory of the Corsican peasant proposed by his father. For him, in any case, and according to this text, whatever the author of the discovery, it is well in Saint-Claude that it was worked in first.

In 1963, another French geographer, Michel Chevalier, professor at the University of Besançon, published an article in the Cahiers de Géographie de Besançon (which he directed) entitled "Tableau industriel de la Franche-Comté 1960-1961". One finds there in particular this: The manufacture of pipes took its modern aspect and became one of the great specialities of St Claude only when, around 1855, the root of the tree heather, native of the Mediterranean countries, was used ...". [7]

Just before that, in 1962, the American pipemaker Carl B. Weber, founder of Weber Pipe Co., wrote The Weber's Guide to pipe in which he took up A. Dunhill's hypothesis, although simplifying it a little:

"... The introduction of briarwood as pipe material was quite accidental. It was linked to the cult of hero worship which sprang up shortly after the death in 1821 of the French emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte. One of those who glorified the emperor's memory was a French pipe maker, who decided to honor his hero by making a pilgrimage to the Mediterranean island of Corsica, Napoleon's birthplace.

Being a passionate smoker, the pipe maker took one of his most beautiful meershaum pipes with him. In a unlucky moment, however, he broke the bowl of his pipe, and was left without mean of smoking. Fortunately, in that same Corsican village there lived a farmer known for his skill in carving. The Frenchman promptly commissionned the farmer to carve a new pipe for him out of any suitable wood.

The farmer soon presented the pipe maker with an attractive pipe, made of a hard, close-grained, pale golden wood. The pipe had so many fine qualities that its owner brought back to France several specimens of the wood from which it was made, the burl of the tree-heath, or bruyere, as it is called in French. Eventually the name Bruyere was anglicized, first into "bruyer", then "brier" and later, "briar"."

"Enthusiastic over his discovery, the pipe maker brought his briar samples to St Claude, a small French town from whose factory he usually bought his wooden pipe stems. This town, located in a remote valley of the Jura mountains, had a remarkable history as a center of wood carving ..." [8]

In 1973 André Paul Bastien published a reference work, entitled The Pipe. He takes up several hypotheses (but not the Corsican hypothesis), but above all he introduces a new testimony (that of Jules Ligier) for the first time to my knowledge. What does A.P. Bastien say?

"... This root of the plant of heather (only part employed for the manufacture of the pipe) comes mainly from the Mediterranean basin. One collects it in France in the Var and Corsica, in Albania, in Spain, in North Africa and in Greece, (Nb He forgot Italy) from where come the most beautiful varieties ...

... From then on, a question immediately comes to mind: how, from the shores of the Mediterranean, did the heather arrive in St Claude? Several hypotheses have been put forward on this subject. Some historians claim that a turner from the area around St Claude, named David, met a local merchant at the Beaucaire fair (near Marseille in the south of France), where he had gone to sell his goods, who suggested that he use this famous root to make pipes. Others state that at the same time and still in Beaucaire, two Sanclaudian delegates, Messrs. Regad and Buat, noticed on an inn table a hardwood container that they were told was briar. They asked permission to work with it, considering it more porous, less fragile and less combustible than cherry wood. But it is probably the thesis of Mr. Jules Ligier, collaborator of a merchant-shipper of the time, which deserves our attention the most. Let us listen to him: "-It was in the first days of October 1858. A traveler, with a somewhat exuberant manner and a very pronounced southern accent, came one morning to the Gay Aîné stores, Place de l'Abbaye, Maison Mallet, on the first floor (in St Claude). He came to make his offers of boxwood stumps, commonly called "broussins", that this merchant bought in rather large quantities for the manufacture of snuffboxes. After having ordered ten thousand kilos of these stumps to be delivered in the course of November, chatting and talking about the grape harvest in the South, Mr. Taffanel, that was him, mysteriously took out of his pocket a small piece of wood, cut to six sides by means of a saw, in the shape of a candle snuffer, the large side pierced roughly with a wick, the small side with a drill and provided with a bamboo stem forming a mouthpiece. Here, he said, is a pipe in which a friend of mine, a shepherd in my village, certified that he had smoked tobacco for more than a year and which, as you can see, is neither burned nor damaged. It was taken from a stump of heather, similar to the stumps of boxwood that you have just asked me about, and which are found in abundance in our region. Mr. Gay, who was very interested in everything that concerned the articles of Saint Claude, questioned him at length. He was given five other pieces of similar heather that Mr. Taffanel had in his pocket and ordered two bags, about ten"grosses"( a "grosse" meant twelve dozens), of the same ebauchons, to be sent in great speed before the end of the month. He had the Saintoyant-Burdet company make horn stems with a flat curved branch and set off on his journey with these samples. The ten "grosses" ordered arrived regularly before the end of October. The company had them finished and assembled in its factory at Plan du Moulin under the suspension bridge, and in the last week of October they left for Paris, northern France and Belgium.

This is exactly when and how the first briar pipes were made in Saint-Claude…" [9]

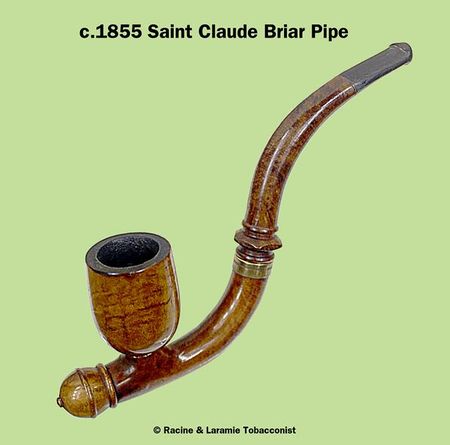

In this regard, let us point out that Racine & Laramie, rather famous merchants of pipes and tobacco in San Diego (USA) (http://www.racineandlaramie.com/index.html), show in Pipedia one of the first briar pipes made in Saint-Claude around 1855.

Here's what they might have looked like:

Saint-Claude briar pipe c.1855, courtesy Racine & Laramie Tobacconist

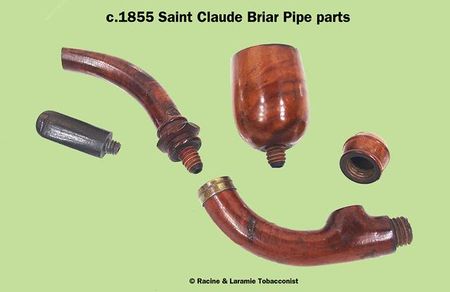

Saint-Claude briar pipe parts c.1855, courtesy Racine & Laramie Tobacconist

"According to local legend a Saint-Claude turner named David is credited with the making the first briar pipe…" (Saint-Claude). [10]

In 1975, a collective work was published in France, l’Encyclopédie du tabac et des fumeurs (the Encyclopedia of tobacco and smokers). We find the Jules Ligier hypothesis and the Regad and Buat hypothesis. In another article, we also find the Corsican hypothesis:

"... Since the day when a French pipe maker, who came to collect himself in Napoleon's birthplace, having broken his meerschaum pipe, asked a Corsican peasant to copy it in a briar root taken from the scrubland, the vast majority of pipes smoked today throughout the world are made from this unique material...". [11]

In 1976, J.W. Cole, in his book The GBD St Claude story, speaking about the founders of the company, states that:

"... Clearsighted as well, they realised the great possibilities of a new matérial, racine de bruyère (erica arborea) which was already being used with success in St Claude in the Jura, and by 1855 Briar GBD pipes were sold ..." [12]

In 1981, Eppe Ramazzotti and Bernard Many published a book entitled Pipes et Fumeurs de Pipes (Pipes and Pipe Smokers), in which the author declares that

"...the first to use the briar for the manufacture of pipes were, it seems, the peasants of the Pyrenees. They cut them roughly in briar logs with a knife. They had a very elongated pyramid shape, with rounded corners; on one of the faces, near the base, the bowl was hollowed out..." [13]

In 1984 a French pipemaker, Gilbert Guyot, wrote a book entitled "Le Pipier de Paris". He discusses the discovery of the heather.

He takes up the Jules Ligier (Taffanel) hypothesis, and introduces another one which would have it that pieces of heather were mixed by chance with pieces of boxwood sent to Saint-Claude to be turned there:

"...Around 1854, heather was discovered by chance: the story goes that a man named Taffanel, a supplier of boxwood stumps and who worked at the Beaucaire fair (the first and oldest of the fairs in France and Navarre), came to take an order for boxwood. Then he took out of his pocket a kind of burner, the large side pierced as a candle snuffer, the other hollowed out with a drill and fitted with a bamboo mouthpiece. According to him, it was the pipe of a Pyrenean shepherd who had been using it for some time without it being burned. Another version commonly accepted in the trade is that Saint-Claude, who received the Mediterranean boxwood, discovered pieces of pink-colored wood of remarkable hardness while exploiting it. The difference was obvious and, as we were informed, it was heather. No one dares to say who holds the exact truth, but it is true that at that time a variety of wood was discovered that had never been exploited before, offering great resources with enormous stumps, old and mature, allowing for unhoped-for yields that have become impossible to find nowadays..." [14]

In 1986, a famous American pipe collector, Richard C. Hacker, published a book entitled "The Ultimate Pipe Book". He is more anecdotal than precise:

"…It is the French who can, in all probability, lay claim for bringing the briar pipe to fruition.

For years, in the small, valley-enclosed village of St. Claude, pipe makers have been practicing their trade and as early as 1800 were experimenting with pipes made out of beechwood and boxwood. Most of these finely carved pipes were created for French nobility, including the elite officer's corps of Napoleon's army, an ironic fact, inasmuch as the emperor himself did not approve of pipe smoking, a prejudice derived from an liquor-laced evening which was climaxed by Napoleon gagging gagging on a bad lot of ragweed. Perhaps inspired by this, the Prussian general Gebhard Von Blücher insisted on raising his pipein the air as he led his troops into battle… which included Waterloo.

Nonetheless, it was around 1840 when a pipemaker named François Comoy (who, in 1825, started the first full-time pipe factory in St Claude) began carving pipes out of France's native bruyere (which has subsquently been called brier and finally briar). [15]

In 1992 Gilbert Guyot came back with a much more complete book : " Les Pipiers Français ". Much more complete, because he obviously knows the testimony of Jules Ligier quoted by A.P. Bastien, since he quotes other elements in his book. Then he completes the Regad and Buat hypothesis already cited by A.P. Bastien:

"...The year cited by Jules Ligier, 1857, brings us precisely to the time of the introduction of briar into the Saint-Claudian pipe industry.

"The story goes that a man named Taffanel, a supplier of boxwood stumps and who worked at the Beaucaire fair (the first and oldest of the fairs in France), came to take an order for broussins.

Then he took out of his pocket a kind of burner, the large side pierced as a candle snuffer, the other hollowed out with a drill and fitted with a bamboo mouthpiece. According to him, it was the pipe of a Pyrenean shepherd who had been using it for some time without it being burned. Another version commonly accepted in the trade is that Saint-Claude, who received the Mediterranean boxwood, discovered pieces of pink-colored wood of remarkable hardness while exploiting it. The difference was obvious and, as we were informed, it was heather. No one dares to say who holds the exact truth, but it is true that at that time a variety of wood was discovered that had never been exploited before and which offered great resources with enormous stumps, old and mature, allowing for unhoped-for yields that have become impossible to find today." [16]

"Jules Ligier still tells as a witness the launching of the briar pipe.

...It was in the first days of October 1858...Gilbert Guyot then takes up the testimony of Jules Ligier quoted above, but he also returns to the REGAD-BUAT hypothesis:

... It is also necessary to hear Mrs PACAUD -FATON, descendant of the old FATON-BUAT families.

The delegates of the Consultative Chamber of Arts and Manufactures REGAD and BUAT went in 1854 to the fair of Beaucaire. At the inn-hostel where they were having their meal, they noticed on the table a container in which there was salt. Curious and interested in this hard wood that they felt between their hands, they had the happy idea to ask for this container whose wood was called heather, to try to work it, in order to replace the birch too easily combustible. This simple and ingenious idea established the heather as early as 1855-1856, which was to supplant all the other types of wood known to this day..." [16]

A little further, another testimony, dating him of 1956 is also quoted by Gilbert Guyot: under the title "text of Mister Henri Vuillard, manufacturer of pipes domiciled in La Coupe, Saint-Claude (Handwritten notes given to Mister Pierre GRAPPIN, then president of the Union Chamber of the Manufacturers of Saint-Claude on the occasion of the Centenary of the Bruyère Pipe -1956):

"...It is said that this material was first brought to Saint-Claude by a southern turner coming from the Beaucaire Wood Fair. An article published in the newspaper La Croix de Saint-Claude announced that it is a woodturner from Chaumont near Saint-Claude, named David, who would have brought to Saint-Claude, coming from the wood fair of Beaucaire, the first specimens of the briar root, the fact is very probable, since it is in the village of Chaumont that the first wooden pipes of the country were made, my father who made wooden pipes around 1860 had confirmed it to me.

It is said that he had even shaped a pipe in a certainly rudimentary way with this wood. What is certain, it is that it took several years to note the shaping of the briar root in Saint-Claude.

It is necessary to consider that to be usable, the root of heather must undergo a rather long preparation. First of all to extract the stump which is at the foot of a shrub that has about 10 to 20 cm in diameter.

In order to be workable, one thousand heads of raw root are needed to obtain about 100 Kg of root that can be cut into a shape that looks like a pipe, which is called the "ébauchon" - a special bath is then needed to avoid some very expensive splinters, which is called " la fente" (the split).

I cannot imagine that briar root pipes were made before 1856 or 1857. In any case, my father, who was a skilled turner living with his parents, farmers in the vicinity of Saint-Claude, often told me that around 1860 he worked with a foot lathe and made pipes from French wood: boxwood, cherry, beech, etc.. My father used to say that he could earn about twenty francs a day, which seemed to me to be a lot of money at a time when potatoes were sold for two or three francs a hundred kilos. A whole calf cost hardly more than thirty francs..." [16]

Gilbert Guyot adds a last hypothesis, which I have not found anywhere else before (except on the site of the Maison Courrieu, and more or less mentioned by Georges Herment; it will appear later in the book of Liebaert and Maya in 1993).

"It is necessary to all these attempts of paternity of discovery of the heather, to retain the thesis which always raises in the trade many controversies and to listen to Mr. René Courrieu, pipe maker in Cogolin in the Var in the south of France). "We find traces of the existence of the Courrieu company in Napoleonic archives. The firm started in 1801, founded by my grandfather Jean-Baptiste.

We are now in the twelfth generation. The heather of the Maures was exploited at the very beginning. Other writings give an account of this fact by which a stump puller from Bormes-les-mimosas, Mr. CHIEZA, undertook to sell to the COURRIEU company all the roots that he would pull out. The descendants of the forester CHIEZA have always attested to the fact that this commercial act was offered to the commune of Bormes-les-mimosas. During an exhibition, it was stolen. In spite of the complaint lodged by Mr. AUVET, great-nephew of the woodcutter, no trace of it was found.

We also have archives (1835) on the proof of exploitation of the heather on the island of Levant. It was then decided to make the convicts of the island's penitentiary work on the pipe. The extraction and the flow were done on the spot, the boiling and the drying of the stumps in Cogolin. After the material was returned to the prison, the final manufacturing was carried out by the inmates. All these pipes were marketed on behalf of the Courrieu company in addition to its own production. The commercial transactions were subject to regulations with the Ministry of Justice, the Prefecture of the Var and the Ministry of the Armed Forces. The island was indeed bought by the French Army at the beginning of the 20th century. The old chimney, the oven, and the ruins of the fort could still be seen more than twenty years ago. Classified as a military site, practically everything on the island has been razed...". [16]

Gilbert Guyot wisely adds:

" So there is no trial, but the debate remains open as to who was the first "discoverer" of the heather, and I would be careful not to decide". [16]

In 1993 A. Liebaert and A Maya make appear The Great History of the Pipe, work in which they recapitulate a good part of the theses quoted previously, by admitting a preference for that brought by Jules Ligier:

... One suspects it, "the inventor" of the ideal wood for the pipe did not deposit a patent and was never identified in a formal way. The mystery of the origin of the briar pipe has thus given rise to several hypotheses, more or less likely, and whose only common point is undeniable: the discovery took place in southern France and developed in the town of Saint-Claude, in the heart of the Jura". The most amusing of these hypotheses is of course the least plausible: a French pipe maker, who was not consoled by the disappearance of Napoleon, went on a pilgrimage to Corsica the same year as the Emperor's death in 1821. After having broken his pipe during a walk, he met a shepherd who made him a pipe, of course in the effigy of Napoleon, in a stump of briar; amazed by the quality of the wood and the taste of the smoke, he brought back to his native Jura a large quantity of stumps and began to treat his smoking contemporaries. Other hypotheses are more serious, such as the one that attributes the discovery to a certain David, a woodturner from Chaumont-les-Saint-Claude, who was informed about the qualities of heather by a merchant he met at the Beaucaire fair around 1855. In his very beautiful book, La Pipe, André Paul Bastien quotes the thesis of a merchant of the time, Jules Ligier, whose precision encourages us to prefer it to the others:

"...It was in the first ... [they reproduce the testimony of Jules Ligier as quoted by A.P.Bastien]."

And they still quote the Courrieu hypothesis:

"...Let us quote again the thesis which grants to the ancestor of a pipe maker of Cogolin, in the Var, the origin of the production in number of the first briar pipes: Ulysse Courrieu, farmer, would have made as early as 1802 some of these miraculous pipes, after having been initiated by a shepherd of the surroundings. His reputation quickly crossed the limits of the canton, inciting the farmer to become a pipe maker..." [17]

Finally another version, would attribute the discovery of the heather to a very big name of the pipe: Comoy.

This version is reported in a document published in the magazine The Tobacco Leaf on November 22, 1952 (of which I unfortunately have not found any trace). The only version I have is a French translation provided by Gervais Pomerleau. Since I only had the French translation, I had to translate it back into English. So these are not quite the original words, but the meaning is there. It says this:

"The story of Comoy began in the Jura mountains :

"François Comoy, a lumberman, noticed the beautiful grain of the heather in 1825.

The history of Comoy's of London is told in a catalog that is currently distributed and in which you can also find the description of all the pipes made by this company..

Throughout the catalog, the leitmotiv "The Oldest Name in Pipes" is repeated. The history of COMOY begins in the town of Saint-Claude, located in the Jura Mountains in France, in the year 1825. François Comoy, a lumberman, observes the beautiful grain of the heather wood, a bold shrub that grows in large quantities in Corsica. We know it today as "briar". With the help of his brothers and his son Louis, he began to make briar pipes and to experiment with the best methods for treating and softening the wood. By 1848, the name Comoy had spread and meant beautiful briar pipes all over the continent. Henri Comoy, Louis' son, soon took over the reins of the growing firm and moved his headquarters to London, which was then the headquarters of the pipe industry.

In 1879, in London, surrounded by a team of French technicians, Henri opened the first pipe factory and began building tools and machines to make better briar pipes. In the 20th century, a new generation of Comoy joined the family business and expanded its market to America. In 1913 the business was moved to Rosberry Avenue, London, and seven years later an addition was built to form the huge building that is now the Comoy's headquarters. Other annexes were opened in the following years. With the outbreak of war, Comoy's was converted to wartime use. The cessation of hostilities saw Comoy's return to making the pipes that are well known throughout the world today."

So what?

To make it simple, we have : the Corsican hypothesis, the Saint-Paul-de-Fenouillet hypothesis, the Cogolin hypothesis, for the place of discovery ; the David hypothesis, the Berrod-Regad hypothesis, those of the turner or the anonymous trader that can be brought closer to the two previous ones, the Comoy hypothesis and finally the Ligier (Taffanel) hypothesis for the discoverer.

Among all these assumptions, there are several constants:

1) The place first

The unanimity seems to be done, even among our English or American cousins, to attribute the paternity of the discovery to the French pipe makers.

The Beaucaire Wood Fair is mentioned on several occasions. This is not surprising. The Beaucaire fair (Beaucaire is a small town near Marseille) was historically very popular, and even though it had lost some of its importance in 1850 compared to the early years of the 19th century, it still attracted a considerable number of people. And then the Erica Arborea was a species from Provence, like the boxwood that had long supplied the turners of Saint-Claude.

On this subject, let us find the testimony of Jules Ligier, quoted several times in the work of Gilbert Guyot: "...Mr. Gay is a member of the consultative chamber of Arts and Manufactures. In 1857 I entered his house to learn the trade. I took part during two years in the preparation of the important stock that this merchant took each year to the fair of Beaucaire. It consisted of all the articles that were made at that time in the region: wooden objects, tonellerie, boissellerie, osserie, toys, wooden and horn snuffboxes, wooden pipes known as MARSEILLAISES and especially wooden or horn pipe stems, BOUQUINS (NB the bits of horn or amber that were adapted to the pipe stem - for example at the end of the albatross bone on the Butz-Choquin Origine), mouthpieces of all kinds intended to be used on clay pipes which were manufactured in fairly large quantities in the Drôme and Marseille, as well as in the whole of the Midi region.

I pay tribute to the ingenuity of the Chaumontier workers (NB de Chaumont, a village that has now become a district of Saint-Claude), because I have seen them at work: the DAVIDs, the REYMONDETS, the GAUTHIERs, the DELAVENNAs, the BRUNETS, the GRILLETS, the GRUETS. They excelled in the manufacture of these charming Marseilles pipes made of hornbeam or cherry wood (the plane or the duret as they called it), whose top of the bowl remained white as sea foam, the bottom and the stem dyed with a special mixture which gave them the appearance of a royally assorted pipe. These pipes were very pretty, very graceful, but the wood was so thin and so combustible that it was necessary to guarantee them with tin, and to protect the top with a circle-shaped metal trim, because in the North of France and in Belgium where they were mainly sold, the tobacco was lit by presenting the pipes on a coal stove. It is with full basket that the Chaumontiers delivered each Saturday, each Sunday morning their work of the week to the house Gay Aîné... ". [16]

We can make a quick estimate here: if this Mr. Ligier entered, let's say at the age of fifteen, in the Gay house, in 1857, he was born in 1842. If he transcribed his memories between his seventieth and his eightieth year (in my opinion, this is a maximum), this testimony can be dated between 1910 and 1920.

One learns there, but one knew it already, that the articles of Saint-Claude included many wooden pipe stems but also wooden pipes, but not yet much in briar, wooden pipes which were manufactured in Saint-Claude since at least the beginning of the XIXth century probably.

Incidentally, I would like to see one of these "MARSEILLAISES" which had nothing to do with Marseille and nothing with the clay pipes that Hippolyte Bonnaud made there. But I am not sure that even one of them has been preserved.

Henri Vuillard, in his testimony quoted above, reminds us that pipes were turned in all sorts of wood at the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, before the exploitation of briar: "In any case my father, who was a skilled pipe turner living with his parents, farmers in the vicinity of Saint-Claude, often told me that around 1860 he worked with a foot lathe and made pipes in French wood: boxwood, cherry, cherry, beech, etc..." [16]

On the precise location in France, there are several hypotheses:

Corsica, first, near Napoleon's birthplace (Napoleon was born at the Villa Bozzi in Ajaccio and it is true that there is heather around Ajaccio). For Corsica, the Comoy hypothesis supports it. It should be noted that it is not known whether Comoy sourced heather from Corsica, the Maures or the Pyrénées Orientales, or even a little of all three (in my opinion, the cost of transport must have had an influence). The Pyrenees Orientales then (Saint-Paul de Fenouillet), there is Erica Arborea in the area and there were indeed wood turners in Saint Paul de Fenouillet, who undoubtedly turned wooden pipes, like a little everywhere at the time.

Moreover, in the Revue des deux Mondes of 1864, an article entitled "Le Travail et les Mœurs dans les Montagnes du Jura - Saint-Claude et Morez" (Work and customs in the Jura Mountains - Saint-Claude and Morez) tells us that "...Today, among the raw materials that are taken from the Jura, we must rank boxwood, whose former stock has been exhausted. This shrub, which grows so slowly, comes almost exclusively from the Pyrenees. The part most sought after by industry is not, as is generally supposed, the root, but an intermediate part called the burl, placed above the roots before the branches and still buried between the stones that cover the ground. The burl provides these veined and flamed articles whose surface can receive the polish of marble and has almost the hardness of it. Just as boxwood, a plant material that is very much in use today, heather root, is collected in the Pyrenees...". [18]

However, this hypothesis appeared only once, mentioned by the honorary deputy director of the Marseille Botanical Garden (the Borély Park of Marcel Pagnol's readers) in 1927. It never came up again afterwards. It does not reappear afterwards, except to be mentioned incidentally by Eppe Ramazzotti. [12]

Les Maures and Cogolin next, a hypothesis claimed by René Courrieu in the 90s. Cogolin was indeed in the heart of the Maures heath, and there have been a number of pipiers in Cogolin, but the oldest and only one that remains is the Maison Courrieu.

Below is a 1981 map [19] showing the location of Erica Arborea in France :

The Jura then. On this subject, concerning the place, it is necessary however to distinguish the place of birth of the heather (the Mediterranean basin inevitably) and the place of birth of the pipe in heather. Indeed if the Erica Arborea does not grow in the Jura, most of the sources agree to say that it is with heather brought back from Beaucaire that the Sanclaudians made the first pipes. It is not known, however, whether it was briar from the Maures, or from the Pyrénées Orientales (both hypotheses are possible).

2) Then the date

Almost all the authors quoted here, French, English, American, and the testimonies of the time, agree on a period between 1850 and 1860.

Alfred Dunhill, who launches the Corsican hypothesis, specifies that the pipe maker's visit to Corsica took place "...in the second decade following his death in 1821...", that is to say from 1841. Dunhill also states that "...and from that date, somewhere in the early fifties, it was destined to supersede all other pipe materials...". Even the hypothesis of the birth of the briar pipe in Saint Paul de Fenouillet dates it to 1850.

In the French Revue des deux Mondes of 1864, an article entitled "Le Travail et les Mœurs dans les Montagnes du Jura - Saint-Claude et Morez" (Work and customs in the Jura Mountains - Saint-Claude and Morez) tells us that "...Today in Saint-Claude it is the pipe, the pipe made of briar root, which provides the work with its principal food. The vogue enjoyed by the rosary before 1790 and the snuffbox before 1830 has passed entirely, for the last five or six years, to these pipes of the simplest work, of a reddish color, that the city and the countryside have also adopted...". [18] .That is to say the first productions between 1850 and 1860.

In The Gentleman's Magazine, July-December 1895, it is stated that "...the old clay pipes and skimmers once famous have been supersede by the elegant and inexpensive "briar pipes" or more correctly "bruyère pipes". For thirty years this semi-mineral has been steadily rising in favour, until to-day..." [20] That is to say again circa 1865.

But on the site of the French company Courrieu, of Cogolin, in the South of France, it is written in particular: As early as 1802, Ulysse Courrieu, a farmer in the region, is said to have made the first heather bouffard and then created the Courrieu factory.

So?

René Courrieu, (according to Gilbert Guyot in 1992) says that "...We find traces of the existence of the Courrieu company in Napoleonic archives. The firm started in 1801, founded by my grandfather Jean-Baptiste. We are now in the twelfth generation. The heather of the Maures was exploited at the very beginning... We also have archives (1835) on the proof of exploitation of the heather on the island of Levant. It was then decided to make the convicts of the penitentiary of the island work on the pipe. The extraction and cutting were done on site, the boiling and drying of the stumps in Cogolin. After the material was returned to the prison, the final manufacturing was carried out by the inmates. All these pipes were marketed on behalf of the Courrieu company in addition to its own production..." What to think of it ?

It is very possible that Ulysse Courrieu turned wooden pipes quite early in the XIXth century, as did the wood turners of the Pyrénées Orientales and the Jura.

Concerning the exploitation of briar on the Ile du Levant, it is true that a prison for children (That was hard times!) was installed on this island opposite Porquerolles where the little convicts, among other tasks, and in sordid conditions that Dickens or Hugo would have been able to describe, were employed to pull out the stumps of briar and then to make pipes. But this prison only opened in 1861.[21] So there is no marked precedence for the manufacture in quantity of briar pipes in Cogolin rather than in Saint-Claude.

It is possible that Ulysse Courrieu started to supply the Grande Armée with pipes as early as 1802. But clay pipes probably, as Basse-Provence (where the Maures massif is located) was at the time not only rich in briar but also in pipe clay, which it supplied to Marseille factories (Hippolyte Bonnaud's factory f.ex.) at the beginning of the 19th century. Wooden pipes too, why not, but probably not in briar. If two or three pipes of briar were made at that time, why not also, it is not outlier that the region of the Maures incited a local pipe maker to use an abundant raw material (at that period).

Also François Comoy would have discovered the Corsican heather in 1825.

3) The circumstances finally

Concerning the fortuitous discovery of the heather by a shepherd, I can't imagine an idle shepherd, finding an Erica Arborea, unstripping it, splitting the burl and saying to himself "Here, I'm making a pipe in it". But why not?

According to Jules Ligier, Taffanel brought a pipe smoked by a shepherd of his region, which according to him "... was taken from a stump of heather, similar to the stumps of boxwood... which are found in abundance in our region ". [16] If heather was regularly used in Provence at that time, the shepherd, like others, could have made a pipe from a piece of heather picked up here or there. The practice could be quite common, but remain confined to the region.

I believe more in the hypothesis of the Beaucaire Wood Fair where wood professionals met, who knew the different species and tested them, and who may well have discovered the briar burl while looking for a substitute for boxwood, and this, perhaps quite early.

That pipiers or turners from St Claude went to Beaucaire to buy wood, and came back with briar burls or blanks, or even simple samples, is in my opinion much more likely. Whether they were Regad and Buat, David or Taffanel, or someone else.

I am a bit divided on the Comoy hypothesis : François Comoy knew wood by his job, wood pipes were already being turned in his region, but the "study trip" of a Jura lumberman to Corsica in 1825 leaves me dubitous (unless he found a sample - at the Beaucaire fair, for example - but probably not in 1825).

Conclusion

To conclude, I believe not only that one should not take one side or the other, but especially that it is impossible.

- That the first briar pipe was first cut in the place where the pipe briar was growing is a very probable fact, but one that can never be proved. And at what date, we will never know either.

- That the briar pipe knew its rise and its fame thanks to the pipe makers of Saint-Claude, it is the most probable hypothesis, the main part of the consulted sources mentioning this city as the manufacturing cradle of the briar pipe. It is thus that the GBD firm produced its first briar pipes in Paris in the last quarter of the XIXth century, from briar coming from Saint-Claude. But also that when Henri Comoy settled in London in 1879 to manufacture briar pipes, it was from the briar of Saint-Claude.

As for who was responsible for this discovery, that's another history. And what does it matter? In my opinion at least....Each of these stories has its charm, and for me they allowed me to discover things that I did not suspect.

References

[1] Dunhill Alfred The Pipe Book, London. First published by A & C Black Ltd, London 1924, and by the Mac Millan Company New York, 1924. The Lyons Press edition 1999, 2002 with preface by Richard Dunhill.

[2] Auguste Chevalier Note sur l'Erica arborea et sur l'emploi de ses souches dans la fabrication des pipes. Revue de botanique appliquée et d'agriculture coloniale, 7ᵉ année, bulletin n°74, octobre 1927

[3] André Mathieu Les petites industries de la montagne dans le Jura français, Annales de Géographie, t. 38, n°215, 1929

[4]Thérèse Colin, Les industries de Saint-Claude. Géocarrefour Année 1937 13-3 pp. 189-206

[5]Georges Herment Traité de la pipe 1965 Denoël Paris

[6] Alfred Henry Dunhill The Gentle Art of Smoking 1954 Max Reinhardt London

[7] Michel Chevalier Tableau industriel de la Franche-Comté 1960-1961 Cahiers de Géographie de Besançon n° 9

[8] Weber Carl. The Weber’s Guide to pipe, 1962, Cornerstone Library Publications, New York

[9] André Paul Bastien La Pipe 1973, Payot Lausanne

[10] Pipedia St Claude

[11] Encyclopédie du tabac et des fumeurs 1975 Le Temps, Paris

[12] J.W. Cole The GBD ST Claude Story 1976 Cadogan Investments Ltd London

[13] Eppe Ramazzotti – Bernard Many Pipes et Fumeurs de pipes 1981 Editions Sous le Vent Paris

[14] Gilbert Guyot Le pipier de Paris, 1984, Club d'Entraide littéraire et artistique, éditions de l'Amateur Paris

[15] Richard Carleton Hacker The Ultimate Pipe Book 1986 Autumn Gold Publishing

[16] Gilbert Guyot Les pipiers français. Histoire et tradition 1992, éditions de l'Amateur Paris

[17] Alexis Libaert & Alain Maya La Grande Histoire de la Pipe 1993, Flammarion Paris

[18] Le Travail et les Mœurs dans les Montagnes du Jura - Saint-Claude et Morez Revue des Deux Mondes, tome 51, 1864 (p. 882-905).

[19] Daniel Alexandrian La bruyère arborescente pour la fabrication des pipes. Revue forestière française (XXXIII . 2 .1 981)

[20] A Chapter on Pipes, The Gentleman’s Magazine, Volume CCLXXIX, July to December 1895, 23

[21] R. Hubsch "La colonie agricole et pénitentiaire de Saint Anne - Ile du Levant - 1861-1878", - B.A.V.T. 1972-94-99.