Satirical Sketches of Pipe Smokers

By Ben Rapaport (April 2022)

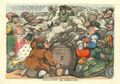

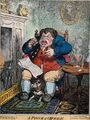

Depictions of tobacco in art date back at least to the pre-Columbian Maya civilization where smoking had religious significance. Since the birth of the medium, prints have been used to disseminate political and social commentary. Seventeenth-century Dutch painters, in particular David Teniers and Adriaen Brouwer, portrayed staid-looking clay pipe smokers in tavern scenes. In the next century, the Georgian era’s Golden Age of British Caricature, also known as the Golden Age of British Satire, the most prolific graphic artists, comic illustrators, and political satirists were three geniuses: George Cruikshank (1792–1878), James Gillray (1756–1815), and Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827). William Hogarth (1697–1764), painter, print maker, and engraver—considered the grandfather of political cartoons—probably influenced these three to focus much of their talent on illustrating pipe smokers and smoking clubs, demonstrating their respective understanding of tobacco as an intoxicant in British life. Some described their work as biting wit and brazen folly.

“Evils from a Prize in the Lottery” (The Monthly Magazine, 1798) noted: “Smoaking was a vulgar, beastly, unfashionable, vile thing” and “would not be suffered in any genteel part of the world.” “One scent that appeared in the diaries, letters, magazines, and literature of 18th-century England, however, was tobacco smoke. The 18 [sic] century saw the rise of new anxieties about personal space. A preoccupation with politeness in public places would prove a problem for pipe smokers” (“The Past Stinks: A Brief History of Smells and Social Spaces,” the conversation.com). I’ll add that It was in the same century that tobacco smoke enemas were popular, a reminder of the familiar phrase—pardon my French—“to blow smoke up one’s arse.”

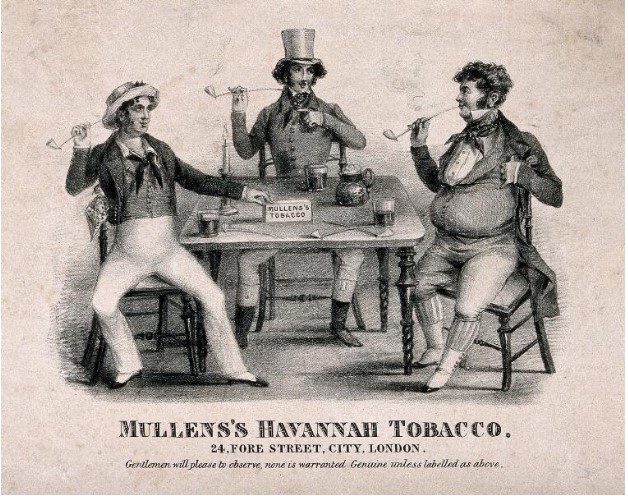

Gentlemen’s clubs functioned with rules and spaces for pipe-smoking, the first opening in London in 1693. Smoking was relegated to alehouses, smoking clubs and private masculine spaces. There are several descriptions of that smoking club of yore. It was that special place where a pipe smoker can mingle with fellow pipers and “blow his cloud,” some called it a pipe room where members “burned their tobacco,” a club where a man could enjoy his pipe as much as he did in his home. It was a special place as a distinguished bishop defined it … a place where “…women cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.”

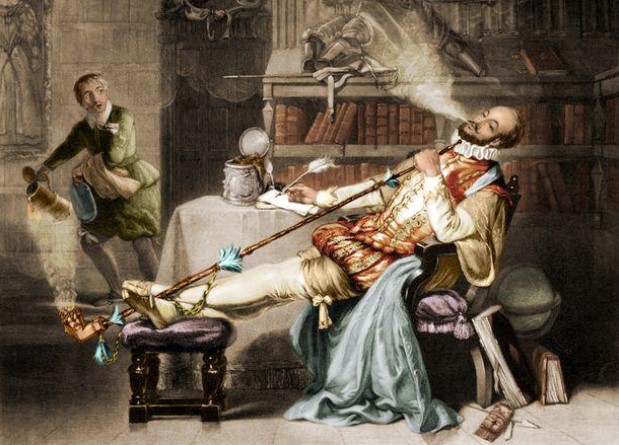

There are many versions of what I consider the most popularized print in tobacco literature, Sir Walter Raleigh being doused by his man-servant.

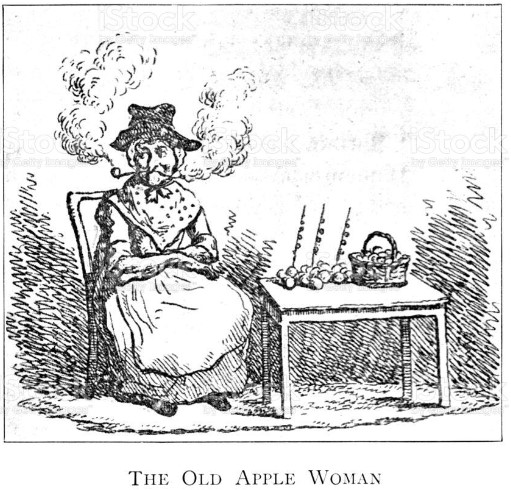

It’s not just men that were portrayed. Here’s one of a woman smoker!

Had this narrative included a similar discussion about period caricatures of cigar smokers, I’d have no trouble finding as many illustrations.

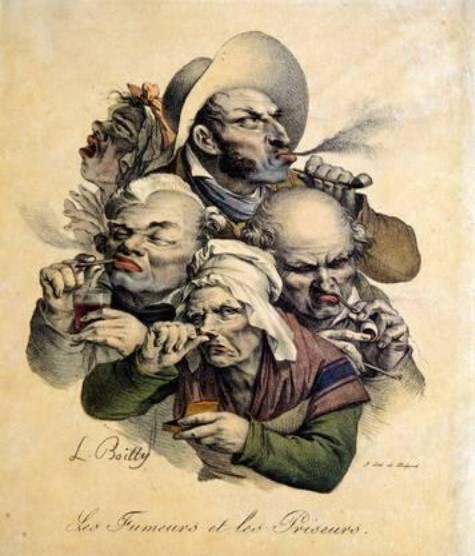

A century later, Cezanne, Daumier, Renoir, Manet, Monet, van Gogh, and lesser-known artists, such as Carl Bloch, Michael Ancher, Albert Anker, and others portrayed pipe smokers in a more realistic, life-like, human format. But the best tobacco-theme caricaturist of the 1800s is, in my opinion, the prolific French artist, Louis-Léopold Boilly who documented French social life. This is an example of his style, “Les Fumeurs et Les Priseurs “(Smokers and Snuffers).

None of these Georgian-era caricatures are very complimentary, and there’s a certain similarity in their disheveled appearance, in their grotesque-looking features. (Caricature is, after all, the distorted presentation of a person, type, or action.) Does it occur to you that these images were meant to convey a specific message: to discourage or dissuade people from taking up the habit? It’s evident to me that this ridicule of pipe smokers was a powerful weapon. The marriage between text and image in Eighteenth–century British prints was certainly “à la mode.” In that age of caricature, the two did not exist independently, but formed part of a dynamic continuum in the way of cutting political and social satire and laughter.

There’s plenty in print, if you desire to learn more about that colorfully graphic era. As you might expect, most of the authors are British and, as this list suggests, and the topic continues to be studied in a variety of university theses and books. Ronald Paulson, “The Tradition of Comic Illustration from Hogarth to Cruikshank” (1973, JSTOR); Hope C. Saska, “Staging the Page: Graphic Caricature in Eighteenth-Century England” (repository.library.brown.edu, 1997); Diana Donald, The Age of Caricature. Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III (1998); Mark Hallett, The Spectacle of Difference. Graphic Satire in the Age of Hogarth (1999); Helen Pierce, “Unseemly Pictures: Political Graphic Satire in England, c. 1600–c. 1650 (etheses.whiterose.ac.uk, 2004); Mark Bills and Ian Hislop, The Art of Satire London in Caricature (2006); Helen Pierce, Unseemly Pictures. Graphic Satire and Politics in Early Modern England (2009); Emily Bastien et al., “Bawdy Brits & West End Wit: Satirical Prints of the Georgian Era” (The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, 2011); James Baker, The Business of Satirical Prints in Late-Georgian England (2017); David Francis Taylor, “The practice of caricature in 18th-century Britain” (compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com), and The Politics of Parody. A Literary History of Caricature, 1760–1830 (2018); Nancy Siegel, “Curious Taste: The Transatlantic Appeal of Satire” (blog.oleahc.wm.edu, March 5, 2020); “The rise and fall of the smoking room, from essential feature to long-gone relic” (Country Life, September 1, 2020); Cynthia Roman, “Smoking Clubs in Graphic Satire and the Anglicizing of Tobacco in Eighteenth-Century Britain” (The Historical Journal, Vol. 65, February 2022); “Intoxicating Spaces. The Impact of New Intoxicants on Urban Spaces in Europe, 1600–1850” (intoxicatingspaces.org); and Stephen J. Bury and Andrew W. Mellon, “British Visual Satire, 18th–20th Centuries” (oxfordartonline.com). Last, the best online source is “British Eighteenth-Century Studies Electronic Resources: Primary Resources: Images” (guides.library.yale.edu) that will link you to several digital collections.

There are many books about the life and times of these three famous British artists, too many to list here, but you could start with a brief introduction to each: “Comic Art in Eighteenth-Century England” (websites.umich.edu). Finally, for the student of tobacco and pipe art—and for the book lovers among us—there are only three books that capture the portraiture of smokers in every century: Luigi Salerno, Tabacco e Fuma Nella Pittura (1954); Enrico D’Anna, Tabacco Storia Arte (1983); and Henk Egbers, Tabak in de Kunst (1987).