The Man Who Carved Clay

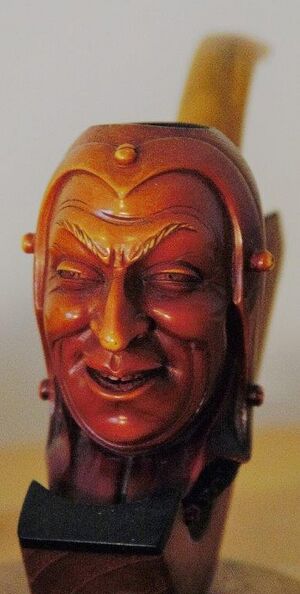

The actors in this story are gone for many years, except for one, and he never drew breath- Gaius Julius Caesar, carved in meerschaum, 9 1/2 inches long, 3 inches tall in a case secured by silver clasps, nestled in a pillow. He comes out to be cradled, prized and smoked.

As men will pass, caretakers have changed over the years. They died mostly unable to say goodbye. One was holding the pipe and it slipped slowly to the rug beside the chair. There was no fire. The keepers have always been concerned about his well-being. They cleaned and kept him dry, looked into his face, wreathed with garlands that never wilt. He was given the best tobacco.

The pipe was smoked in the evening, lifted gently from his carriage, a slow and private pleasure. Then the packing of the bowl, lighting and rising smoke. The wooden match's flash, euphoria and a clear perception of forever.

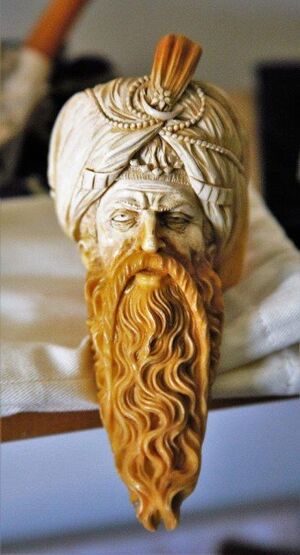

Life for Caesar started underground near Eskisehir in Central Turkey. What we call meerschaum slept one million years, growing stronger and waiting. Then men came, knowing the place, how to work the pit and what to do with the clay. Mined with shovel and pick, it came away hard, torn to light from the silence and dark it was accustomed to. It was deep, down 100 meters, pulled from the earth by hand, a chunk the size of a large fruit held with cupped hands, washed in a stream of clear water, brushed and left to dry on grass. It was graded for purity and to decide which workman would receive it from the plain where it was drawn.

Taken to the harbor of Izmir by cart, it was graded once more and sewn in a bag of brown Indian jute, put into lots for France, England, Italy, Austria and America. The sac was marked for weight, city of delivery; the name of the buyer attached by a tag was marked with a code. A prison, but release and the future were coming. The Arab ship with the lateen sail departed the port, the sea was calm and the voyage uneventful.

Discharge was at Ancona in the Marche region of Italy, a single bag taken by wagon to the town of the carver. Other goods as well --- spices, women's items and coffee. The clay heard a new language. The trip took days; the block was patient.

When young, a boy was apprenticed to an artisan for seven years in a large town where men moved to the side on the streets during market days. The master saw in the young man's hands an ability to find souls and not waste. To bring life and make pipes, turning warmth in the bowl to comfort the mind. The young man did well and his skills increased. Knowledge was shared; he stayed past the obligation. Then, it was time to go. More than a decade from youth, he packed his tools and walked to a quiet part of the country. He needed a village where the world came with the settimanale, time and events filtered by distance and the pace of walking horses.

He lived in a hill town between mountain and sky. The houses were small and low, had good light and the wind was free. The sun could not be blocked by order, written in the Civil Statuti, first edition, 1543. He entered the town through the gate where vegetables were delivered. Men worked the fields beyond the thick walls. He was a converso and no one knew. On holidays he kissed a fragment of the Torah hidden in the pages of a book. Home and work were the same. He lived alone, coming to the town without a woman. He needed only a table, high sun, tools, patience, water to soften

the clay, and time to find his subject in the white pieces stolen from the earth.

The blocks in the jute bag were separated and laid out, resting while the carver considered. A man, woman, couples making love, a pair of horses, a parrot and monkey. Figures of mythology or simple pure design, battle scene, a fantasy. The family remembered from childhood, neighbors at the market and collectors of excrement.

The carver had a preference for men 's faces in his pipes. He found anger, pity, compassion, the lines of age, strength of chin, the stubble of a new grown beard, gentleness. With delicate tools he could display vision, passion and hypocrisy, the sadness of love. The face could have a hat or scarf, locks of gold or thin, the disfigurements of disease. He read history and wanted to carve different races and working men, damaged or restored. The real, not smooth countenances of privilege that hid cruelty and indifference. He valued the men with battles etched on their bodies and scars within. If you could bring it out, they spoke of conquest and exhausting defeat. He carved the people of his village, prosperous and impoverished, the woman who lost her husband, the cripple, a priest at the door of his church with a supplicant, a blind man walking, imprinted by a lifetime on the same paths, the young beautiful girl.

He had a patron in the south who would buy his pipes and be thankful. The man had purchased a Nubian, an American Indian, an Irishman. The carver had seen none of these but there were books.

The clay that came in the sack from Turkey had substance. The workman saw the face of Caesar and decided he was a worthy subject in middle age, when the certainty of death at the hands of friends was known, but not which friends. As his hair receded, before the damaged body and his walk faltered. With eyes that commanded armies and would go flaccid on marble in a crowd of hate, fear and jealousy.

The work began in the midday sun, the block on the table. There were knives and scrapers, smoothing and other tools, fine abrasives. The art and wonder were not in the tools. It was feeling that guided the knife. The shape began to come out, details of the nose, cheeks, severe lips. Slow work to make the face whole, time to find the man's core. He had seen it before. The carver offered himself through the blade and from Caesar something was returned in fair exchange.

The bowl and the airway were drilled, the stem of amber attached, a coating of wax applied, case made of dried paper and cotton, covered with leather and the carver's name engraved. Caesar lay in velvet, embraced in silk. The pipe was put on a shelf in the sleeping room.

One autumn rain afternoon the pipe went to Rome, offered, examined and approved in the store on the good street with a silver sign above the door. The pipe sold and the account settled. The carver continued to work. He did not follow his creations and knew they went to all manner of men, professionals, laborers, an ignorant man who desired a fine smoking pipe and took advice, those who appreciated the art. Sometimes a person felt the carver. The pipes changed hands, there was no archive, and so became lost. He labored for many years and the pipes went into the world. They were smoked, touched and enjoyed, sometimes broken and sent for repair. People admired the craft, looked for meaning and saw themselves.

Toward the end of his life, he decided to carve himself in a massive piece of meerschaum. It took months of afternoons when he shut out the world. Complete, he put it aside. A friend who was present said it grew in the hand and struggled. The carver said, non c'è passato, tutto è dentro di noi ora.

The date and cause of the carver's death are unknown. A request on parchment was found in his house. A cemetery in a nearby village held the few graves of Jews from centuries before. He wanted to be with them. The wish was granted because the village had affection for the man who worked at a table in the sun. The service was short and Christian. His tools were given away, furniture went for taxes. Over time, the lettering on the headstone eroded, the marker fell and was covered in brush. The comune has the records if you ask.

It is 160 years since Caesar's birth at the hand of the carver. The pipe spent years in a drawer or cabinet. The country saw war, times of peace and the cycle of seasons, of plenty and drought. The owners became wealthy and died in debt. Title and property passed to children and the barren wife. One man was given Caesar as a boy, a present from parents who saw the past and estimated the future. They shared five decades. The pipe was treasured, safe from cold and never mistreated. When the case was opened, the boy believed the pipe was aware. Strangers assumed it could not see or hear.

Once the pipe was sold through a second hand shop. Young people looked and imagined far voyages and travels. They asked if it smoked well, was the face accurate. The salesman, who stood above the cracked and taped glass case, had no answers and preferred to describe discounted furniture and cheap jewelry. One man thought it was an accessory and attractive to his wife.

A single foglio was found when the pipe was offered for sale in the middle of the last century. No signature appears but the hand in old script is from a father. The paper was pressed into the case, following the form, beneath the pipe. It said, “ Son, enjoy the pipe. Learn the lessons of the man you hold in your hand.” This is the only evidence of provenance, other than the etched name of the maker.

In the early part of our new century, the pipe has been in the showroom of an antique boutique in Milan. It sits near an old globe with a parrot standing on Africa. There are trays of butterflies and a wooden medical model of a man's body with stethoscope. Few ask to see the pipe. You can buy a new briar pipe in a cardboard box for fifty euros at the tobacco store. Somewhere along the years and the high speed superstrada, the pipe is overlooked. In time it will be sold. It is on the internet and millions can find it on their screens. Someone is looking for Gaius Julius Caesar. The clay can wait and the secrets will keep.

David Gerstel

Sarnano, Italy

dgerstel@securenet.net