The Native-American Peace Pipe (or Pipe of Peace). Two Terms Often Used as Symbol, Idiom, and Metaphor

Exclusive to pipedia.org [1]

Introduction

What is a peace pipe? When asked this question, some may conjure mental images of Indigenous people from cartoons, old Western movies, and books about who smoked these pipes with European settlers to seal a treaty. However, many of these depictions are fraught with inaccuracies and stereotypes. Fundamentally, as Edward P. Morris (On Principles and Methods in Latin Syntax) explains: “The general meaning of the word pipe is very simple, and its range of application is wide, but it has many special meanings which belong to it only in certain connections.” This is especially true for the stereotypical phrase peace pipe.”

The peace pipe, also known as the pipe of peace and, less often, the sacred pipe or Calumet, is something that most readers should be familiar with. It’s the term that refers to a ceremonial pipe smoked by our First Americans. Joseph D. McGuire (Pipes and Smoking Customs of the American Aborigines) asserts that the French adopted the pipe as an emblem of peace about 1673. “The name ‘Calumet’ is considered a French corruption of the original Indian name for the river whose precise meaning is uncertain. Geologist and historian Kenneth Schoon suggests it may have alternately referred to the river’s deep still waters or to the river’s native reeds that were used as peace pipes” (Gavin Van Horn and Dave Aftandilian, eds., City Creatures, 2015).

The peace pipe was used to commune with the animate powers of the universe, embodying the honor and the source of the power who possessed them. It was used in prayer offerings, ceremonial commitments, sealing a treaty or covenant, rites of passage, and soul-keeping. Quoting a Sioux Medicine Man: “The Pipe is us! The stem is our backbone, the bowl our head, the stone our blood. …The opening in the bowl is our mouth, and the smoke rising from it, is our breath, the visible breath of our people.” The Lenapé people of Delaware believed that “as the smoke from the pipe rises to the sky, your thoughts and prayers will be heard by the Creator. Peace and order, and good thinking will be restored among the people.”

The National Park Service (“The Power of the Pipe,” nps.gov) offers a different viewpoint: “Although many people associate Native American pipes with the term ‘peace pipe,’ this is a misnomer. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, “The term ’Peace Pipe’ came into being as a result of whites encountering them at treaty signings,” which is a much narrower definition. In Covenant-Making. The Fabric of Relationship, the authors Charles J. Conniry and Laura K. Simmons write: “In fact, the use of the pipe for most tribes is much more sacred than assumed by the White Men who made treaties with Native Americans. A more accurate description would be to call it a ‘Covenant Pipe.’”

As a ceremonial pipe, its construct varied, but executed most often in pipestone—Catlinite (considered to be the blood and bones of buffalo)—from the quarries of Minnesota, with a wood stem covered with rawhide or buckskin, often adorned with feathers, horse hair, quills, ribbons, and beads, and a deer or elkhorn bowl and mouthpiece. John Stands had this view: “After white man came, the Sioux made their pipes out of this stone [pipestone], and seen white man with corn cob pipes setting up on top, and that’s how they came to make peace pipes the way they are now” (John Stands in Timber and Margot Liberty, A Cheyenne Voice. The Complete John Stands in Timber Interview, 2013).

“George A. West [Tobacco Pipes and Smoking Customs of the North American Indian] called it [the peace pipe] the circular or chief’s pipe. He noted, without a citation, that this pipe can have up to fourteen stems. …One such ancient peace pipe was reportedly found in Pike County, Illinois. It is three inches in diameter, does not have legs, and has five holes for the inserting of legs and stems” (Thomas John Blumer, Catawba Indian Pottery, 2004). Suffice to say that different tribes have different pipes for different uses.

“The smoke in the peace pipe means many things. It may be the smoke given off by the fires of passion or the intoxicating scent of love itself. Most importantly it is the breath of words, spoken from the heart, seeking true understanding and union” (Teresa Moorey, The Fairy Bible, 2008). (Smoking the peace pipe is frequently mentioned in The Book of Phil, His Life Amongst the Lamanites [The Book of Zelph. Another Testament of the Book of Mormon, 2018]. In The Book of Mormon, the Indians are called Lamanites.) According to Evan T. Pritchard: “The term ‘peace pipe’ is something of a stereotype (along with the phrase ‘smokum peace-pipe’ and other insulting doggerel”) (Native American Stories of the Sacred Annotated & Explained, 2005).

“Unlike the majority of smoking pipes, the peace pipe carries positive connotations even in Soviet children’s literature. It acquires political, anti-racist overtones, since Soviet writers associate it with the extermination of Indians by their white oppressors. In a poem by Agnia Barto, a curious shift occurs: smoking a peace pipe is a Soviet game unknown to American children. When an American boy, a tourist ‘playing Indians’ with Russian Young Pioneers, behaves violently, oppressing the ‘Indians,’ the Pioneers teach him to smoke a peace pipe” (Milla Fedorova, Yankees in Petrograd, Bolsheviks in New York, 2013).

Incidentally, there are at least two analogous events. “The ‘Pipe of Peace’ undoubtedly has the same significance as the ‘Communal Feast’ among the Arabs and other races” (A. A. Brill, “Tobacco and the Individual,” in The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Volume III, 1922). And a different interpretation on the Continent. “When in Europe a person presents his snuff-box to the friend who sits beside him, the act has precisely the same meaning as when the pipe of peace goes round in the wigwam of the savage” (Johann Georg Kohl, Travels in Ireland, 1844).

Assorted Pipes and Their Uses

“War and Peace Pipes. Commemoration and Remembrance” (Pipes & Tobaccos magazine, Spring 2008) was my report about pipes of another era. In this story, I examine the history of the peace pipe and pipe of peace beyond the colloquial “Put that in your peace-pipe and smoke it.” This essay is the whole what’s what about these two terms.

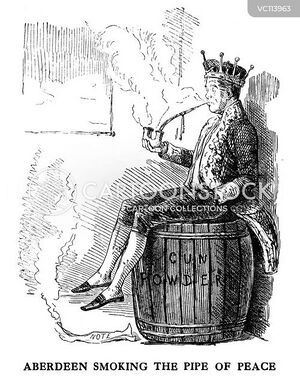

As you might expect, the interpretations are many and varied. This cartoon of Lord Aberdeen appeared in Mr. Punch’s History of Modern England (1921). (see at right)

Lord Aberdeen is not smoking a typical peace pipe and neither is this woman (on the left). The caption is “A Dutch Pipe of Peace” of the late 17th century.” It’s not Dutch and it’s not from the 17th or even the 18th century. It’s a 19th-century German wood Gesteckpfeife, and probably made as a trade sign for a tobacco shop.

According to David Steel, this World War One, London-made clay pipe depicting Lord Kitchener, found on Scotland’s May National Nature Reserve in May 2022, is a peace pipe! Unlikely! (see bellow)

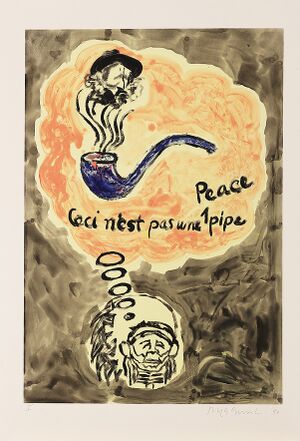

This 19th-century, walrus-ivory pipe in the Allen Memorial Art Museum (Oberlin College), attributed to the Iñupiat of Alaska, is catalogued as a peace pipe. Borrowing the title of René Magritte’s 1929 surrealist painting, “Cec i n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”), I say: Ceci n’est pas une calumet de la paix!

The caption of this graphic is “Seneca Chief Cornplanter and his peace pipe tomahawk.” President George Washington gifted this pipe to him in 1792 during negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Canandaigua. It is now in the Seneca Iroquois National Museum and Cultural Center, Salamanca, New York. I prefer a more precise description: “tomahawk peace pipe axe.” I always considered that a tomahawk, with or without a pipe bowl, was a weapon of war. It’s a uniquely oxymoronic North-American tool where the threat of war and the hope of peace frequently coexisted.

I subscribe to the studied opinion of George Catlin’s Letters and Notes on the North American Indians: “Two of the tomahawks that I have named, marked e, are what are denominated ‘pipe-tomahawks,’ as the heads of them are formed into bowls like a pipe, in which tobacco is put, and they smoke through the handle. These are the most valued of an Indian’s weapons…deadly weapons of war.” “Although the pipe is frequently called a Peace Pipe, there is also a War Pipe used to organize and lead war parties. A Tomahawk Pipe was also used both in connection with peace and war” (Paul B. Steinmetz, The Sacred Pipe, 1998). At one end of the tomahawk pipe is the lip for the pipe; at the other end is the ax blade and a pipe bowl, indicating the warrior’s willingness to use the one side that allows him to offer the other.

“The war is over. The lawyers are being paid and the pipe of peace actually has been smoked. It was smoked at the annual dinner of the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers, which occurred in the Hotel Astor, New York, on Thursday last, 12th inst. …The sentiment was well received and loudly applauded, and then to cement the newly formed friendship the pipe of peace was smoked. It was a long church-warden pipe at which President Clifton took the first pull” (“Pipe of Peace Smoked at A.L.A.M. Banquet,” The Motor World, Vol. XXVI, No. 1, January 5, 1911).

Ray I. Hoffman, reflecting on World War One, expressed it this way in “The Pipe of Peace” (The United Shield, April, 1916):

“Oh! Pass around the pipe of peace and let this doggoned warfare cease—enough, I say, enough! Be it a corncob or a briar—just fill that blackened bowl with fire—let each one take a puff. Bring forth the clay or calabash and charge it with tobacco hash and take an awful whiff. It’s time they cut this broadsword play—just pass the pipe around to-day and end that foolish tiff. A little pipe of cocoawood will serve the purpose just as good. A meerschaum, too, would do, but, anyhow, just fill the bowl and smoke to reach the peaceful goal, and blow forth smoke clouds blue.”

This pipe was used at Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, in the early 1900s during Class Day ceremonies. Seniors would take a puff from this clay pipe, identified as a peace pipe. Unfortunately, the ceremony was deeply problematic, because it stereotyped and appropriated Native peoples.

Beginning in 1905, the junior and senior classes at Indiana University would put their feuds to rest by smoking a pipe together at a peace pipe ceremony. On Commencement Day, students from each class would gather on Jordan Field—what is now the Indiana Memorial Union’s parking lot—to retell stories of their disputes, and then pass around the peace pipe to settle their rivalries. The peace pipe was donated by the Class of 1905, and it became one of the most distinctive Commencement traditions. Today, the pipe is housed in the University Archives.

Close inspection of this 1943 photo reveals that this pipe is purely symbolic; it couldn’t be smoked. The photo exhibits only the stem work of a German Reservisten (regimental) porcelain pipe from the time of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871).

There was a Pipe of Peace ceremony for the class of 1921 to 1922 and 1922 to 1923 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where members of the senior class would pass down words of wisdom and guidance to the juniors and then engage in the ritual smoking of the peace pipe as an act of togetherness, while typically wearing historic Native American attire. This photo depicts nine Wisconsin University juniors and seniors, dressed as Native Americans, going through the motions of smoking the peace pipe on the Mendota lakeshore, Madison, Wisconsin, in June 1931.

The ritual seems to have spread to other American universities. This photo of Yale graduates is dated June 17, 1935. They’re not participating in a sit-in cum peace-pipe ceremony; they’re puffing clay churchwardens, not Calumets, to celebrate their passage from college.

Pomona and Claremont McKenna College in eastern Los Angeles County had exchanged a Native-American peace pipe at every football game since 1959, but this tradition ended in 2013, when both schools recognized the inappropriate use of a peace pipe as a trophy.

Gayle Worland, “’Sifting and Reckoning’: UW-Madison exhibit puts past discrimination on display” (Wisconsin State Journal, September 10, 2022) writes: “Visitors to ‘Sifting and Reckoning’ can see historical objects such as the ‘Pipe of Peace’ used in campus rituals to parody Native American ceremonies until around 1940.”

Artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith titled her 1993 monotype, “Ceci N’est Pas Une Peace Pipe I.”

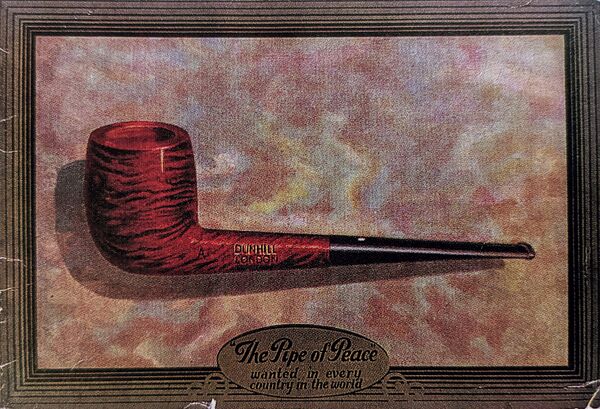

This is the opening line of the Introduction to “Dunhill, The Pipe of Peace” at pipedia.org: “For the everyday smoke what more is there to say than this, that it is, in its essence the Pipe of Peace?” I may not agree with the appellation, but I agree with the sentiment.

The Sterncrest ad exhibits its interpretation of the Pipe of Peace.

A gallery of interesting examples

In 2009, Canadian Cree artist Dwayne Frost crafted a peace pipe as a hybrid of American clay and German wood for the annual celebration of Karl May Days in Radebeul, Germany.

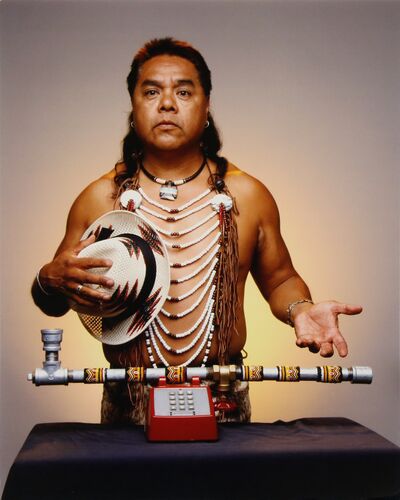

What about this high-tech, conceptual-art, futuristic peace pipe from the late James Luna? (see left). His view is: “A high-tech peace pipe is very possible, but, at the same time unrealistic. It’s a play on words—people think all Indians have peace pipes, so I took this literally and constructed a peace pipe out of [metal] pipes” (“High-Tech Peace Pipe. An Interview with James Luna,” News From Native California, Spring, 2001).

This modern peace pipe made of laminated wood is designed smoke you know what.

Richard Krueger enlightens the reader about all the new technologies that have been adapted to today’s cool smoking devices in “The High Tech Evolution of the Peace Pipe” (cannabismagazine.com). Timberado gives peace pipes a new life with this ensemble, an American revival of the Chinese opium pipe of a century ago!

There are many contemporary meerschaum pipes that are peace pipes in symbol only. This peace sign was designed by Gerald Holtom for the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1958.

This bizarre-looking creation is advertised as a “Native American Peace Pipe.”

And here’s another interpretation. “Our Native American Peace Pipe is handcrafted from wood and ideal for display. These quality, historically accurate wooden pipes come with ceramic bowls and are fully functional. …Era: American Revolutionary War.”

More bizarre is to watch the Harald Baldr YouTube video, “Vietnam Peace Pipe Fail,” in which he smokes a bamboo pipe that he calls a peace pipe.

Talk about truth in advertising, in April 2023, this “Vintage Tomahawk Tobacco Smoking Pipe” was for sale on Etsy.

Mr. Bróg (Poland) has produced a series of Mediterranean briar and pearwood pipes. Here’s an example of what he calls a “Lakota Indian Peace Pear Wood Tobacco Pipe.”

The Peace Pipe in Various Contexts

Now to the substance of this essay. I hope that what follows is enlightening, entertaining, and educational. You might even be surprised. Its scope is a salmagundi of odds and ends, but what is common throughout are the many references to peace pipe/pipe of peace that have been used to identify different things, places, and activities. Some have taken liberties with these words for brand imagery. Both terms have become figures of speech and used in surprising ways; I include lots of assorted and unexpected things named peace pipe and pipe of peace.

The columnist Chris Holguin posted “Americans need to stop abusing the peace pipe” (The Bowdoin Orient, September 23, 2016). His dispute was with the U.S. Government. My dispute is with these two words. This October 2013 quotation is attributed to the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. When he was asked: “Had you already arrived at originalism as a philosophy?” Part of his answer was: “Words have meaning. And their meaning doesn’t change.” Many words have changed as have meanings through time … and many words have more than one meaning, interpretation or connotation. The pipe of peace and the peace pipe are polysemous expressions, i.e., both have several meanings, both are culturally-sensitive words. The pipe, as a symbol, has been manipulated and used in different ways for different purposes in different contexts. I want to chronicle all the ways that these two terms, once attributed to a sacred object, have been appropriated and colloquialized—occasionally trivialized—and have become secular, materialistic, or mundane in the non-religious sense of the sacred and the profane. Wherever found and however applied, some of what follows befits Ripley’s column, Believe It or Not. Shakespeare’s Juliet asked: “What’s in a name?” You’re about to find out.

Music

The anonymously-composed “Song of Big Ben,” published in the March 15, 1877 issue of Truth, contains these lines: “There the braves unite to ponder,\On the present and the future;\There they smoke the pipe, Meer-sham-ah,\Smoke the pipe of peace, Meer-sham-ah;… The Peace Pipe. Cantata for Mixed Voices (1915) is Frederick S. Converse’s chorale with mixed voices and a baritone solo for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s words from “The Song of Hiawatha” that he had written in 1855; Part I is “The Peace-Pipe.” “Pass That Peace Pipe” was a 1947 Oscar-nominated song. “Smoke My Peace Pipe (Smoke It Right)” by the Wild Magnolias was released in 1973. “Peace Pipe” by the B.T. Express debuted on Soul Train in 1975. If you are into Beatles music, you may have listened to the fourth, solo-studio album of Paul McCartney, “Pipes of Peace,” released in 1983, consisting of lyrics describing the Christmas Day Truce during World War One. Johnny J. Blair and the Rover Boys, “Pipe of Peace,” is a 1990 Chippewa Indian song. Cry of Love’s band’s hit-single, “Peace Pipe,” was released in 1993. In 2004, Cerulean City’s hit was “We Smoke ‘em Peace Pipe.” The artist Nickodemus released “Peace Pipe” in 2005 and, in the same year, there was Robert L. Hanson, “Song of the Peace Pipe.” In 2008, Aaron Ross/Shapeshifter song, “Pass the Peace Pipe,” was released. Emerson Windy song/video, “Peace Pipe,” was released in 2014. The New Orleans group, Tin Men, released “Smoke My Peace Pipe” in 2019. Street Slang’s song, “Peace Pipe,” and “Peace Pipe” from Bronx VI were both released in 2021. Peace Pipe Gypsy’s music is on Spotify. And in 2023, there’s “Peace Pipe-Peace Tape VIII” and “Peace Pipe by The Shadows. According to lyrics.com, there are 2,446 lyrics, 109 artists, and 49 albums matching pipe of peace.

Literary Works

Edward Vincent Heward, St. Nicotine of the Peace Pipe (1909) is the only book solely and wholly about pipes and tobacco. Lous Seig, Tobacco, Peace Pipes, and Indians (1971) examines the many ceremonial uses of tobacco among the native peoples of North America. As to other books with the title peace pipe or pipe of peace, there are, literally, several shelf’s-worth by authors of both non-fiction and fiction who have chosen these words for the title for different reasons and for different subject matter. A book titled peace pipes could be about theater organs or bagpipes or, for example, Penn Rabb, Tomahawk and Peace Pipe, the history of the 179th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division. Suffice to say, lots of books bear either title, from the first, Vitulus, A Light for the Pipe of Peace. A Word to John Bull from One of His Calves (c. 1750) to the most recent, Patrick Dearan, Comanche Peace Pipe. The Old West Adventures of Fish Rawlings (2023). Two book titles intrigued me. Roz Weaver’s Smoke the Peace Pipe (2020) is a metaphor for coming to terms with her trauma. Steven Andree’s The Peace Pipe (2022) retells the history of the human race with integrated references to Chinese characters, Middle Eastern culture, the Garden of Eden, and biblical narratives. And, having mentioned biblical narratives, I add the title of Chapter 11 of Alexei Bodrov and Stephen M. Garrett (eds.), Theology and the Political. Theo-political Reflections on Contemporary Politics in Ecumenical Conversation (2021), “The Prince of Peace Smokes a Peace Pipe: A Church Response to the Challenge of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.” The savior as smoker?

And periodicals. The Westerner Company introduced The Peace Pipe Magazine of Cheerful Spirit and Gentle Nature beginning in 1910; it was described as a miniature magazine of gentle nature and cheerful spirit. Peace Pipe Aficionado was a recent, short-lived pseudo-magazine for Native Americans who enjoyed smoking peace pipes.

One can find either term employed in unusual ways. Helen Wells, “How Bunny Smoked the Peace-Pipe” appeared in Little Folks. A Magazine For Young People (1901). Anna E. Parrish published her fairy tale, “Benard at the Fish Convention” (The Continent, November 10, 1910). In this tall tale, the peace pipe is a fish. Just so you know, there is a real freshwater pipefish with the scientific name Syngnathinae.

“The bookseller was smoking the peace pipe, sitting on the complete works of Jules Romains, who designed them for that purpose. He had a very pretty briar peace pipe, which he filled with olive tree leaves. He also had next to him a bowl to spit in, and a moist towel to cool his forehead and a bottle of Ricqlès mint alcohol to strengthen the effect of the peace pipe” (Boris Vian, Foam of the Daze, 2003). Briar peace pipe? And this from a misguided youth:

“Have you ever noticed that pipe thing in the front part of the church that people put quarters in?” “Yeah.” “It’s called a peace pipe.” “Okay.” “It’s called Heifer Project. They’re trying to solve world hunger. They think if people aren’t hungry it will be easier to have peace.” Robby waited. “That’s why they call it a peace pipe” (David Krewson, Robby Braveheart. A Novel, 2011).

“Not only that, but the kissing and making up after an argument can be a delicious way to remind both of you just how much you mean to each other. The Americans call this ‘peace pipe sex’ and it can help you reconnect emotionally when you find yourselves in two opposing camps” (Madeleine Lowe, Stop Kissing Frogs. How to Avoid Mr Wrong and Find Mr Right, 2012). “Justine suspected that the puppy, a pug named Dartmouth, had been a kind of peace pipe, to be regarded as the end of the braces discussion” (Bill Cotter, The Parallel Apartments, 2013). “Peace is an oft used word with multiple meanings. It can affect various parts of one’s physical being. …One can have a piece of apple pie when thinking about how to make peace at their place of business. ..Instead of a peace pipe, how about a piece of chocolate layer cake or a hostess cupcake?” (Al Paulvin, The Ramblings of a Broken Heart, 2020).

Places

Pipe of Peace is a tobacco shop in Nassau, Bahamas. Quoting from Ian Fleming’s Thunderball (1961): “The girl gave a cheerful wave of a sunburned hand, raced up the street in second, and stopped in front of The Pipe of Peace, the Dunhills of Nassau.” It’s still in operation, and claims to have the largest selection of pipes in the world.

There’s a chain of Peace Pipe smoke shops in Florida and similar establishments with the same name everywhere across the country … too many to list. An Edison, New Jersey, store has an unusual name, Smokin’ Devils Peace Pipe. There’s the Peace Pipe Cannabis Company in Oklahoma, and The Peace Pipe Cannabis Company with five retail locations in Canada. There’s a Peace Pipe Café in Richardson, Texas and one in Granbury, Texas, the Peace Pipe Bar (hookah lounge) in Charlotte, North Carolina, one in faraway Almaty, Kazakhstan, and many others everywhere you look.

There’s the Peace Pipe Country Club in Denville, New Jersey, and the Pipe-O-Peace Golf Course in Riverdale, Illinois. The Peace Pipe Lounge is a guest house in Montrose, Colorado, the Peace Pipe Motel in Diamond Point, New York, and Peace Pipe Vista in Park Rapids, Minnesota. There’s Peacepipe Arroyo Rock Climbing within the McKelligon Canyon in Texas. The Treaty City Motorcycle Club of Greenville, Ohio, hosts the annual Peace Pipe Enduro series of races, and Vermont’s Mount Snow Carinthia Park Ski Resort hosts the annual Peace Pipe snowboard event.

Look at any map in detail and you’ll find addresses such as Peace Pipe Place, Peace Pipe Road, Peace Pipe Drive, Peace Pipe Bend, Peace Pipe Way, Peace Pipe Court, and Peace Pipe Lane. West Hammond, Illinois, founded in 1868, was renamed Calumet City in 1924, and there are 12 other places in the world named Calumet. In Rachel Field’s book of fiction, And Now Tomorrow (2022), Peace-Pipe is a mill in New England. Coreorgonel was an 18th-century Native-American Village in what is now Tompkins County, New York. Its translation is “Where we keep the pipe of peace.”

People and…

This is a short list. If I am to believe radaris.com, the people-search engine, there is one person named Peace Pipe living in each of the following states: Indiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. The Peace Pipe Players of Maquoketa, Iowa, is a media and entertainment company. The Peace Pipe Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution is in Denver, Colorado. Concert organizers, Peace Pipe Productions, uses crossed calabashes as its logo.

Pipe of Peace was a thoroughbred stallion born in Great Britain in 1954 and, in 2015, Peace Pipe was foaled in California.

Things

“To signal engineers, the ‘pipes of peace’ are signal pipes painted with Dixon’s Silica-Graphite Paint. In peace of mind it is worth much to the man in the tower to know that the pipes under his operation are …” (“Signal Pipes, Boston Terminal Station,” Graphite, June 1913). In the late 1960s, there was a system called Peace Pipe that could pinpoint ground locations to within 25 yards with the aircraft as much as 50 miles from the drop zone. And I’m not surprised to find several, tasteless slang definitions of the phrase pass the peace pipe in the urban dictionary, most of which are not repeatable here.

I’ll not list the many artists whose paintings bear the title “The Pipe of Peace,” “The Peace Pipe,” and “Peace Pipe”; there a more than a few. The Presidential medals of Thomas Jefferson, Martin van Buren and John Tyler are incised with two clasped hands, a tomahawk, a pipe, and the message, “Peace and Friendship.” Pipe of Peace was card number 188 in a set of 216 Indian Chewing Gum trade cards from Boston’s Goudy Gum Company. Worthy Brewing, Bend, Oregon, introduced Peace Pipe Porter in 2016. Peace Pipe is a popular drink consisting of Peleton mezcal, orange curacao, yellow chartreuse, jalapeno chili infusion, lime, orange, and ice.

The Nicotiana sylvestris, also known as the Indian Peace Pipe, is a perennial plant that blooms in the summer. And to further your botanical education, the Ghost Plant, a wildflower of the Adirondacks and Hocking County, Ohio, also known as Indian pipe (Montropa uniflora), corpse plant, death plant, and ghost flower, is said to resemble a Native American peace pipe. Geum triflorum JS ‘Peace Pipe’ is a perennial known as grandfather’s beard or lion’s beard.

This quotation is from Wm. Demuth Company magazine ads of the 1900s: “The Wellington Pipe of today represents the world’s greatest value—the universal pipe of peace.” “Missouri’s production of corn cob pipes, the modern pipes of peace which make tobacco taste the sweetest, mounted in 1909 to 27,733,260 pipes, as compared with 24,671,460 pipes for the year 1908” (“Missouri’s Corn Cob Pipe Industry,” Surplus Products Missouri Counties for the Year Ending Jan. 1, 1910).

A Tuxedo tobacco ad from around 1915: “For ‘The Smoke of Battle’ and the ‘Pipe of Peace.’ Here are today’s marching orders. …It’s good for you when you’re going into action—and when you’re at peace with the world.” This ad is not far-fetched: “Among other achievements, they [Knights of Columbus] helped to make the Christmas of 1918 a most memorable one for hundreds of thousands of young Americans in France by the distribution of thousands of peace pipes, by extra supplies of chocolate and tobacco, and, at least one section, by the distribution of plum pudding cooked by a noted expert chef” (Maurice F. Egan and John J. B. Kennedy, The Knights of Columbus in Peace and War, 1920).

From a 1926 ad for Granger Rough Cut tobacco: “Granger makes a peace-pipe of a bucking briar. It is, in fact, a peace-pipe smoke.” Peace Pipe Smoking Blend is a mixture of nine relaxing herbs specially blended to provide a peaceful and pleasurable smoking experience, sold by Grandfather’s Spirit, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Metaphor

There are many examples of the term used figuratively as an attention-grabbing headline. Words and context matter. I’ve included a few examples.

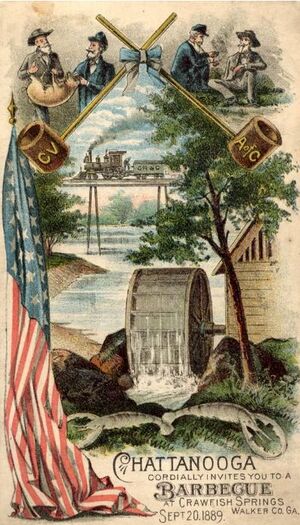

Daryl Black describes the souvenir program for a Civil War remembrance in 1889:

The representation of smoking works in two ways. First, it brings to mind the camaraderie of shared smoke—a common form of relaxation during war. It no doubt conjured images of the informal truces during the siege of Chattanooga, when pickets from opposing armies met between the lines to trade and socialize. A shared bowl of southern tobacco was a hallmark of these meetings. …One of the ways they [Americans] did this was to appropriate Native American symbols as references to elemental aspects of authentic American culture. …The appearance of the pipes on the cover of the program was not coincidental. In the first lines of text the visual reference on the cover is made clear: ‘Chattanooga Welcomes the Blue and Gray to a Barbeque to Be Given on Veterans Day on the Chickamauga Battle Field, Where They Will Smoke the Pipe of Peace, and Bid Each Thought of Conflict Cease.’ To carry the metaphor further, the seventh act of the event was to ‘Light the Pipe of Peace. Made With Wood Cut on Chickamauga Battlefield’” (Daryl Black, Relics of Reunion. Souvenirs and Memory at Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, 1889-1895, in Lawrence A. Kreiser Jr. and Randal W. Allred, The Civil War in Popular Culture, 2014).

“We all know how everyone dislikes the yearly event of spring cleaning, more especially the sterner sex, who if they are wise would try and vanish from the scene of action. However, many are quite unable to do so; therefore try and do your cleaning as comfortably as you can, always having one sitting-room where they can go and smoke the peace pipe” (“Spring Cleaning, As Done in English Homes,” Good Housekeeping, May 10, 1890).

“Probably it is some relic of this superstition, which makes men more civilised think it their solemn obligation to retire into the sanctum of a smoking room or a club in Pall-Mall or elsewhere, when they wish to sacrifice tobacco to the manes of the more sophisticated Peace-Pipe whose name is Meerschaum?” (Cope’s Smoke Room Booklets. Number Nine. Pipes and Meerschaum. Part The First. American Pipes, 1895).

“Smoking the peace pipe in wartime” was a piece in the Cosmopolitan, September 1923, from Hugh Livingstone, Adjutant of Yankee Division Post No. 272 of the VFW, complaining that there was never enough tobacco distributed to the Doughboys to satisfy their need. And here’s a witty play on words, a poem in celebration of Tobacco Week (Tobacco, February 7, 1924): “All smokers now may, so to speak.\Smoke up. This is Tobacco Week.\All in America, we may state,\Have double cause to celebrate.\For in our country, Heaven be praised,\Tobacco was first born and raised.\ And by religious rites invoked\The pungent leaves were lit and smoked.\And warriors would their battles cease\To quietly smoke the Pipe of Peace.\But customs change and culture ripe\Has turned it to a piece of pipe.” “Pretty cigarette girls are now gardenia maidens and cigarettes are passed around in the manner of peace-pipes at dinner parties” (“Cigarette Shortage,” Brief, Vol. 2, No. 6, January 9, 1945).

If you’ve read Stephen King’s 1977 novel, The Shining, or seen Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 movie interpretation—one of at least 10 interpretations—this symbolism may interest you:

“…in Kubrick’s telling it is not the ghosts of ‘Indians’ who haunt the Overlook but those of the European perpetrators.) All that is left of Native Americans are the artifacts littered throughout the hotel in the form of the decorations in the Colorado (Spanish for ‘red’) Lounge, the ‘Indian chief’ logo on the cans of Calumet (meaning ‘peace pipe’) baking powder conspicuously displayed in the kitchen storeroom…” (Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door. Stanley Kubrick, History, & the Holocaust, 2004).

Seeking shelter from mounting liability suits, the headline in The Wall Street Journal on April 16, 1997, was: “Peace Pipe: Philip Morris, RJR Talk Settlement With Plaintiffs.” In the same year, France and the Netherlands held a mini-summit on drug policy, and the politico.eu headline read: “Peace pipe on offer in drugs policy conflict.” Another 1997 headline appeared in the Los Angeles Times on December 3: “The Peace Pipe Eludes Modern ‘Pilgrims’ and Indians,” about a confrontation with police and the arrests of more than two dozen members of the United American Indians of New England’s day of mourning march. James M. Wall, “No Peace Pipe: The Stated Goal of Bush Appointee Daniel Pipes—an Israeli Victory and a Palestinian Defeat” (Christian Century, September 20, 2003).

“In fact, marijuana was one of the few common-ground experiences left in Vietnam, with dope sometimes being shared and passed between white and black soldiers like a peace pipe” (Martin Torgoff, Can’t Find My Way Home. America in the Great Stoned Age, 2004). In 2005, the UN Refugee Agency announced: “Rival ethnic groups smoke peace pipe in Liberia’s Lofa County.” The reconciliation was not the ritualistic sharing of a smoke by the Lorma and Mandingo tribes, but the slaughter of a cow.

“The smoke in the peace pipe means many things. It may be the smoke given off by the fires of passion or the intoxicating scent of love itself. Most importantly it is the breath of words, spoken from the heart, seeking true understanding and union” (Teresa Moorey, The Fairy Bible, 2008). The Deseret News, August 2, 2009: “Obama’s modern peace pipe” was about his invitation to Henry Louis Gates and Police Sergeant James Crowley to share a beer at the White House. “Netflix Smokes a $50 Million Peace Pipe With the Satanic Temple” (nasdaq.com) was about the Satanic Temple’s lawsuit against the Netflix show, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. Best-selling author, Ta-Nehisi Coates used this metaphor: “I was peace pipes and treaties. My style was to talk and duck. It was an animal tactic, playing dead in hopes that the predators would move to an actual fight” (The Beautiful Struggle, 2009). “It is David’s Heavenly Pastoral; a surpassing ode, which none of the daughters of music can excel. The clarion of war here gives place to the pipe of peace, and he who so lately bewailed the woes of the Shepherd tunefully rehearses the joys of the flock” (Charles H. Spurgeon, “The Treasury of David,” romans45.org).).

A Much Different Pipe of Peace

I’ve saved this for last. Today, for some, tobacco smoke is inhaled. Centuries ago, smoke was inserted into another body orifice, the rectum. An early example of European use of this procedure was described in 1686 by Thomas Sydenham who, to cure iliac passion prescribed bleeding, followed by a tobacco-smoke enema. Physicians in Europe used it as treatment for a range of ailments, from colds to cholera. Intra-rectal insufflation was a resuscitation method for drowning victims in the 17th century.

The year 1774 was significant for two events. Evans & Company, London, manufactured a resuscitator that was designed to revive people who were apparently dead by inserting tobacco smoke into the lungs through the nose or mouth … into the rectum. And a Dr. Houlston of Liverpool published an appropriate rhyme: “Tobacco glyster (enema), breathe and bleed./Keep warm and rub till you succeed./And spare no pains for what you do;/May one day be repaid to you.”

More interesting is what Dr. Sterling Haynes claimed in his December 2012 article, “Tobacco Smoke Enemas” (BC Medical Journal) referring to our first Americans: “Inspired by an American First Nations custom, tobacco smoke enemas were administered by medical practitioners in the 18th century to treat everything from colds to cholera ….Word of this treatment crossed the water to England, and volunteer medical assistants with the society began to use the procedure to treat half-drowned London citizens who were pulled from the Thames River. Initially the ‘pipe smoker London Medic’ inserted an enema tube with rubber tubing attachments into the victim and blew smoke into the rectum.” Quoting Amanda Pederson: “Blowing smoke up your backside wasn’t always a figure of speech” (bioworld.com).

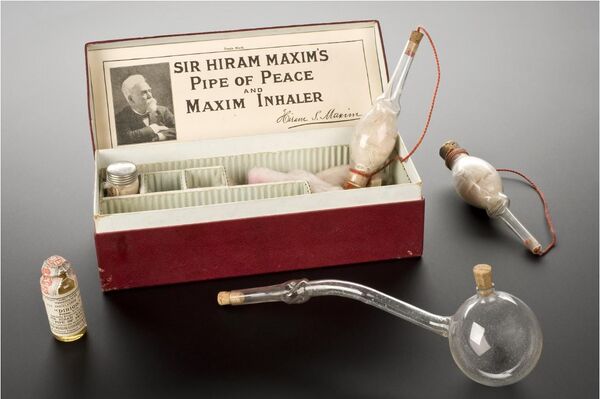

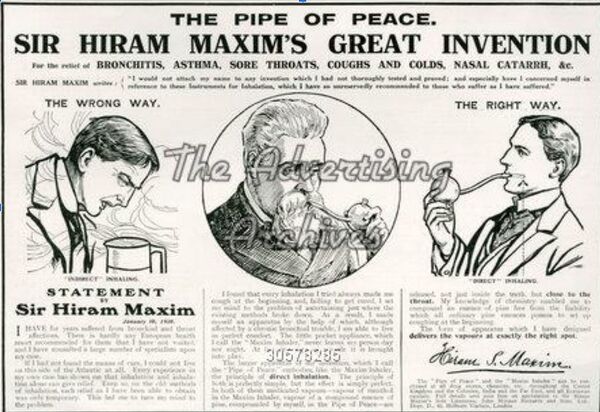

And from tobacco-smoke enemas to a non-smoke inhalantor and the culmination of this story. Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim (1840–1916), an American-British inventor, is best known as the creator of the first automatic machine gun, the Maxim gun. Some called him “the engineer of death.” Maxim held patents on numerous mechanical devices, such as hair-curling irons, a mousetrap, and steam pumps. He laid claim to inventing the lightbulb. He became a naturalized Briton in 1899 and, in 1901, Queen Victoria knighted him for his inventions. He was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006.

He was a longtime sufferer of bronchitis, and he patented and manufactured a pocket-size mentholinhaler and a large “Pipe of Peace,” steam inhaler using pine vapor to soothe the throat, c. 1909-1910. He claimed that it could relieve asthma, tinnitus, hay fever, and catarrh. It was also used to treat throat and chest problems such as bronchitis. Soothing vapours from water warmed with a few drops of “Dirigo,” made from Maxim’s own recipe, a mixture of liquid menthol and wintergreen oil, could be delivered right to the back of the throat via a long, swan-necked glass tube. After being criticized for applying his talents to quackery, he protested that “It will be seen that it is a very creditable thing to invent a killing machine, and nothing less than a disgrace to invent an apparatus to prevent human suffering.” Despite being an inventor his whole life, people found it hard to believe that this pipe would work. They accused Maxim of promoting fake medical practices. Eventually, word of its effectiveness spread, the inhaler became very popular and, by the early 1900s, hundreds of thousands had been sold.

Writing about Maxim’s famous machine gun and his Pipe of Peace, in 2001, Stephanie Pain asked in “War and peace” (newscientist.com): “Had Maxim done with death and turned peacemaker?” “The words ‘Maxim’ and peace somehow don’t seem to go together.” And Paul Cornish asserted: “This [inhaler] was successfully marketed under a somewhat ironic appellation: ‘Sir Hiram Maxim’s Pipe of Peace’” (Machine Guns and The Great War, 2009).

This pipe of peace is no peace pipe, but Maxim and the other man in this ad sure look like they’re smoking. Etsy.com offers an assortment of glass peace pipes that have an uncanny similarity to Maxim’s glass bulb. The comparison is not lost on me.

In Conclusion

This exhaustive study has multiple levels of meaning, and I’ve made every effort to focus on one objective, to demonstrate that the peace pipe and the pipe of peace have meant and continue to mean different things at different times to different people. In closing, a few lofty quotes—historical nuggets—from George Edward Lockwood, “Pipes of Peace Idealistic Emblems of a Practical Smoker’s World” (Tobacco, August 19, 1926) are appropriate:

This mighty instrument of good will [the pipe] was found more powerful than the sword, so settling the tangles of intertribal disputes. It was utilized for such purposes more often than warfare. Just as the pen has time and again been found more powerful than the sword, so the pipe of peace has, time without number, been found more forceful than the arbitrament of war. And there can be no doubt that the character of the smoking mixture used in the pipes was a preponderating factor in promoting its conquests. The pipe of peace has played so many historical and social roles in American history that it is now looked upon as one of the most characteristic symbols of the United States. …The world’s authorities on international law, however, believe that the nations can be educated up to the pipe of peace type of diplomacy, and they have devised many plans for introducing it. The remodelled [sic] Hague conference and tribunal are some of them, and the League of Nations is another.

What can confidently be stated is that Native Americans smoked the venerated, ceremonial, sacred Pipe. Today’s briar is not considered sacred in the definitional sense of spiritual or sanctified; it’s certainly not ceremonial, nor is it worshiped, but it is venerated in the sense that it is valued and treasured. If the distinctively rigorous ritual of pipe-smoking is followed, the result can be a divine, spiritual and, I dare say, heavenly, experience!

- ↑ If it were not for Scott Thile’s expansive online forum and his willingness to accept my occasional stories—especially this one that is not wholly about pipe or tobacco history—you would not be able to read it elsewhere on the Web. Thank you, Scott!

Thank you, Ben! Pipedia would not be the resource it is if not for contributors like you!