Ikebana

Introduction

Tsuge's Ikebana line of pipes have sometimes been referred to as 'The Flowers of the Pipe World', which makes sense--the literal translation of Ikebana is living flowers, which refers to the high form of Japanese floral arrangement. The practice and presentation of an Ikebana arrangement is said to encourage silence, and an appreciation of nature that is sometimes overlooked in the rush of our busy lives. It is also said to encourage the appreciation of beauty in all art forms. For years the Tsuge brothers have entrusted the over site of their Ikebana line to Kazuhiro Fukuda.

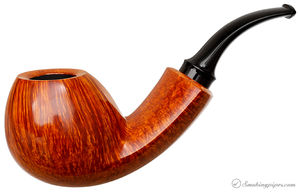

A Beautiful Tsuge Ikebana Freehand, Courtesy Smokingpipes.com

Tsuge Ikebana's New Pipemaker

In November of 2013, a new and exciting pipe maker was announced as Fukuda's heir apparent. The following article by Sykes Wilford appears courtesy of smokingpipes.com

As a woman in her late 20s, Asami Kikuchi is something of a rarity in pipe making. Indeed, she's even more of a rarity in Japanese pipe making. There are just a handful of female high-grade pipe makers in the world and all of them, save Kikuchi, have been either the daughter or the spouse of a pipe maker. Kikuchi's path has been unusual, a serendipitous road to a career she never thought existed, let alone longed for, a few years ago.

In her fourth year at Tama Art University, one of Japan's most illustrious art schools, Kikuchi undertook an unusual project. Most of her fellow students worked on architectural projects or industrial design projects--chairs, tables and the like--or in more traditional, solely visual arts. Kikuchi became fascinated with wood. More specifically, she became captivated by the tactile experiences made possible through the creation of small wooden objects; their potential to soothe, stimulate, and delight. In an art school in Europe or the United States, this would seem particularly odd, but in Japan, with its history of highly artistic, small handcrafted goods, while it was still a little unusual, there was, at least, a framework for doing this sort of work. Kikuchi says that when she started the project, everyone from friends to professors was a bit bemused by the whole idea. It seriously deviated from the sorts of things art students did, but as she worked through the project, they came to understand.

In an interesting twist of fate, the supervising professor for that final art school project was a childhood friend of Kyozaburo (Sab) Tsuge's wife. A couple of years after she finished art school she was contacted by this professor because of the similarity in underlying idea between her final project and pipe making: both in wood and both highly tactile as well as visual. It didn't go anywhere for a little while, but when Kikuchi received an order for a number of her small wooden sculptures and needed access to a workshop to make them, she reached out to Tsuge and he offered her use of the Tsuge workshop in Asakusa after hours. And from there, she fell in love with the process of pipe making. It was as if she'd always wanted to make pipes, but waiting to discover that handmade pipes existed. It was the perfect fit for the sort of work she had always wanted to do.

- Ikebana workshop, Sep. 2014, Fukuda-san and Ms. Kikuchi, Courtesy J Rex Poggenpohl

Having completed the project for her client, she asked Tsuge if she could stay and learn to make pipes. Fukuda, primary carver for the Ikebana line for four decades, is in his seventies and while he's in great health and still remarkably productive, Sab Tsuge and others have been looking for someone to learn, supplement Fukuda's work, and, in time, guide the Ikebana line into the future. Sab Tsuge cautioned her that it wouldn't be easy, and then gladly welcomed her aboard.

According to Kikuchi, Fukuda is pretty old school. While not quite ‘Wax on, wax off’, the learning process involved a lot of watching, while Fukuda happily answered her questions. Fukuda, grounded in an older tradition of craftsmanship, treated it far more as a master-apprentice relationship than a teacher-student relationship. He had her do useful tasks that also got her accustomed to the machinery and the sorts of work that would be necessary for pipe making. And he set very high standards, quietly spurring her on towards better and better work.

She's been making pipes full-time with Tsuge for a little over a year now. Ryota, 'Our Man in Japan', Shimizu, and I first saw her work in December, 2012. We were immediately impressed and saw the enormous potential she had. Almost a year later, she's at a level where her work would fits perfectly in the Ikebana line. Stylistically, she gravitates to some different shapes from Fukuda, but the underlying work is just as sound. Of course, Sab Tsuge certainly thinks so: the Ikebana stamp is something of a company--and Tsuge family--treasure, not something to be applied lightly.

As Sab Tsuge said, "while she'd never encountered pipes, her work at university had such a remarkable affinity to pipes. When I saw the small sculptures Kikuchi had made, I immediately thought that she could make pipes."

Traditional Mentorship: Pipe Crafting Anachronism?

By R. Bear Graves, courtesy, smokingpipes.com

Given that nearly all of the lauded artisans/masters who have emerged over the past decade began, and progressed, in their art largely of their own efforts, with only internet forums, the occasional ‘workshop’ and the rare 1-2 day stopover at a senior carver's place, it would be fair to ask: “Is there still a place for a staunchly traditional Master/student relationship?” Given the amazing debut pipes of Asami Kikuchi, I believe the answer is ‘yes’. Due to the required alignment of situations and circumstances between both parties, however, the actual chances of such a relationship forming ranges between ‘highly unlikely’ to ‘damned near impossible’.

Even though residing within the same city, the combination of timing, factors and coincidence required for the Tsuge/Fukuda/Kikuchi match to occur would have Vegas bookmakers scratching their collective heads - and yet it happened. Kazuhiro Fukuda needed a successor. A talented art student, with a demonstrated affinity for working with small wooden objects realized that, for her entire life, this was what she was born to do, but simply needed exposure to the idea in order to realize it. An agreement was struck, and the most traditional/formal of Master/apprenticeships began, within the framework of (arguably) the most formal of artisanal societies: Japan.

By traditional standards, while Kikuchi didn’t have to wait (in the rain) in front of the master’s door to gain eventual entry, her apprentice path began with arriving every day and prepping her master’s work area. From there, she was allowed to handle small, indirectly related tasks and quietly ask questions. On the cusp of apprentice and journeyman, the crucial steps in creating a perfect airflow were addressed, the kohai begins to help with sanding, and even takes the first faltering steps of carving discarded blocks. Depending on the teacher, even at this early stage, the sensei might demand an opinion regarding a shape in progress. While her answer was inevitably ‘wrong’, and the teacher patiently explains why, this is where the two parties begin to truly connect with each other’s approach to visualization, as it addresses translating the idea of a shape, into the corporeal. By the time Kikuchi hit advanced journeyman, if her art was regarded more advanced than any other, save the master, the kohai becomes sempai (think ‘top student’) and helps mentor others, as well as now having a full hand in the creation of pipes worthy of the top marque. It is at about this point where progress stops being discussed, and, often for months, the obvious (but never referred to) question hangs in the air. One day, deliberately calculated as a surprise and often falling on the heels of being taken to task over some small detail, the master (and principles, if involved) will suddenly appear, smile broadly, and confer the status the student has so diligently pursued.

Asami Kikuchi went from a simple awareness that briar could represent the pinnacle of a carver’s art, to the new Master of one of the most revered pipe marques in the world in less than a year. Something that, at first blush, would seem highly improbable, until you ask yourself what results might occur from (say) a Jeff Gracik spending eight hours a day, six days a week, right next to a Teddy Knudsen, when both knew that a new master needed to step on the world stage in less than a year. Yes, the traditional master/apprentice system still works.