The General and the Captain: Two Period Pipes of the Early Twentieth Century

Exclusive to pipedia.org

Introduction

In the first quarter of the Twentieth Century, two atypical briar pipes were in production: the General Dawes and the Captain Warren. We all probably have a degree of familiarity with these two pipe formats, but what about their history? You can easily find something about General Dawes on Wikipedia, pipedia, several other websites, in books, and in news clippings … a fire hose-full of information. Nary a word on Captain Warren. And how did both pipes get their names? Again, the General Dawes pipe was prominent in its day, the Captain Warren pipe? Well, read on.

Curiosity did not kill this cat, so I began a search resulting in a substantive narrative about both the persons and the pipes. I think that you’ll find it a fascinating and exhaustive, but not exhausting, slice of pipe history. (Some who have read my articles in Pipes & Tobaccos magazine or on pipedia.org, have told me that many of my tobacco and pipe topics are irrelevant for today’s pipe-smokers. Others have called me a babble-merchant or a master of prolixity, a sesquipedalian rather than a simple story teller. And others have said that when asked the time of day, I often build a watch. Perhaps, but this story is too good not to tell it.)

Before I get into the granular details, what’s the distinguishing difference between the two pipes? The Dawes usually (generally, almost always) had a flat-ish or setter bottom, and the Captain Warren usually (generally, almost always) had a round-ish bottom. “On a lighter note, smokers might be interested to learn that [General] Dawes popularized the Dawes pipe. If you’ve never seen one, think of the letter P. Now rotate it ninety degrees to the right, and you’ll get the idea” (John R. Schmidt, Hidden Chicago Landmarks, 2019).

Warren: The Man

Who was this Warren fellow? There were lots of Warrens in the last half of the 19th and early 20th century in England and in the United States, with and without first names or initials, with and without titles or military ranks, so I narrowed my search to those with any affiliation with pipes. Slim evidence of one is in the last stanza of the poem, “Nicotina”: “A hero has been found to baulk\The wiles of the tobacco fairy.\All smokers will his efforts bless,\Of compliments not one is barren\For Nicotina’s naughtiness\Is tamed at last by Captain Warren!” (Fun, Vol. V, November 2, 1867). The only mention of a pipe is in one stanza: “The Poet’s Pipe is all the go.”

“He [Captain Warren] was an inveterate smoker and in those days always smoked a clay pipe with a stem not to exceed an inch in length. There were no matches at that time and a coal had to be used to light up with” (Annals of Jackson County Iowa, 1905). “I bear a letter to thee by good Captain Warren of the Sprite. He hath also brought me a box of new tobacco, fresh from America” (“Sojourners. A play in One Act,” The Drama. A Monthly Review, November, 1919). There was a Captain Warren in Joseph Crosby Lincoln’s Cap’n Warren’s Wards (1919) who said: “But I tell you, Jim—just now you said something about a pipe. I’ve got mine aboard, but I ain’t dared to smoke it since I left South Denboro. If you wouldn’t mind—.” “The fanciful description goes on to picture Captain Warren sitting on this veranda, ‘smoking a comforting pipe after his mid-day dinner’” (Anna Alice Chapin, The Gallant Career of Sir Peter Warren, 1920); he was an 18th century Anglo-Irish Navy Captain.

A few of today’s pipe smokers have posited that it was Sir Charles Warren (1840–1927), an officer in the British Royal Engineers who rose to the rank of General. The time frame seems about right, but wouldn’t his pipe have been called the General Warren? What about Charles B. Warren (1870–1936) whom cigar-smoking Calvin Coolidge nominated to be his Attorney General, described as “…a shambling, bookish, pipe-smoking, trout-fishing, kindly man” (M. C. Murphy, Calvin Coolidge, 2023). He was an American diplomat and U.S. Ambassador to Japan from 1921–1923. He also fits the time frame, but he had not served in the military. Is it possible that, because the first Captain Warren pipes were manufactured in Great Britain (illustrated later in this article), they might have been named for a Captain Warren of the British military or a captain of British industry. I’ll have more to say about the Captain later in this article.

Dawes: The Man

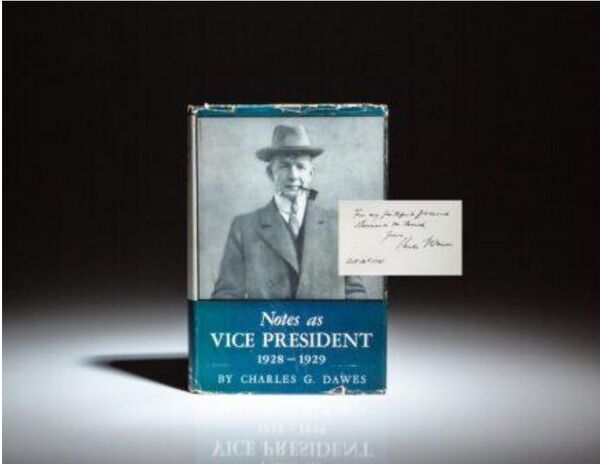

The first Dawes of significance was John Thomas Dawes, 4, Clayton Square, Liverpool, recipient of Patent No.21,801 for improvements in tobacco pipes (Tobacco, December 1, 1896). But he was not the famous Dawes. Charles Gates Dawes (1865–1951) was an accomplished man. He was a U.S. Army Brigadier General, U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain, Vice President to Calvin Coolidge, accomplished musician and composer, Nobel Prize winner, on the cover of Time magazine, December 14, 1926 and June 11, 1928, and the subject of a feature story, “Man Behind the Pipe” (Time, June 23, 1924). He was a prolific writer: The Banking of the United States (1894); Essays and Speeches (1915); A Journal of the Great War (1921); The First Year of the Budget (1922); Notes as Vice President. 1928–1929 (1935); A Journal of Reparations (1939); Journal as Ambassador to Great Britain (1939); and A Journal of the McKinley Years (1950.) And a handful of books have been written about his life.

He was a man of colorful characteristics, famous for his tart language and his contempt for pomp. And, as you’ll discover, he was inextricably linked to his pipe … he was never without it! His party used his pipe as an emblem and as a giveaway in his 1924 campaign for Vice President to Calvin Coolidge.

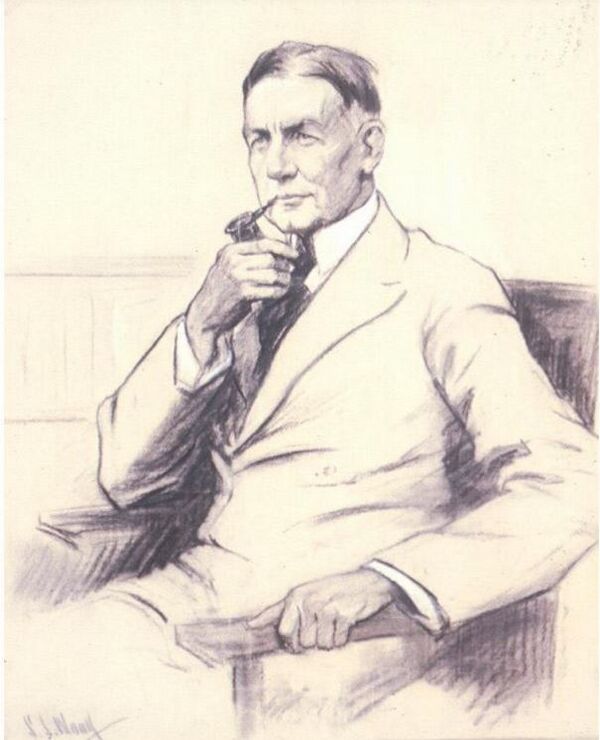

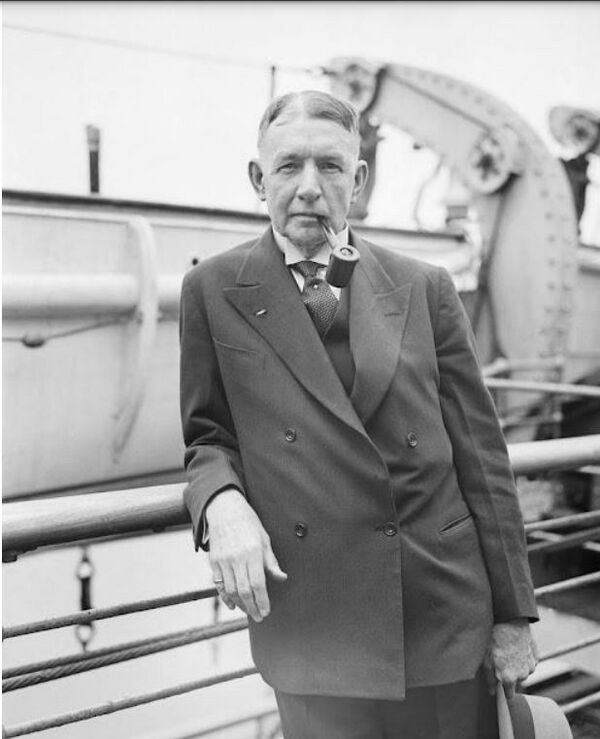

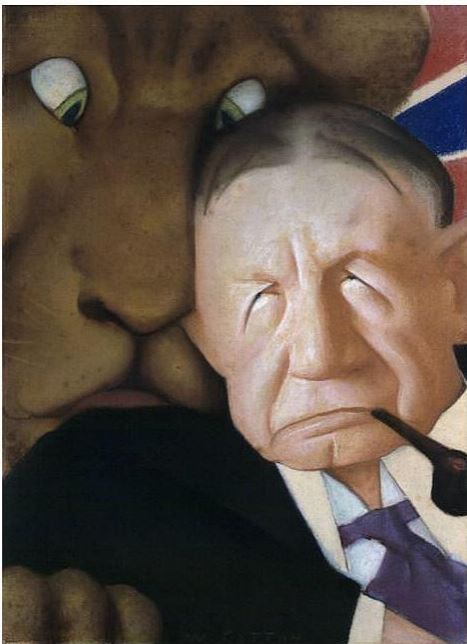

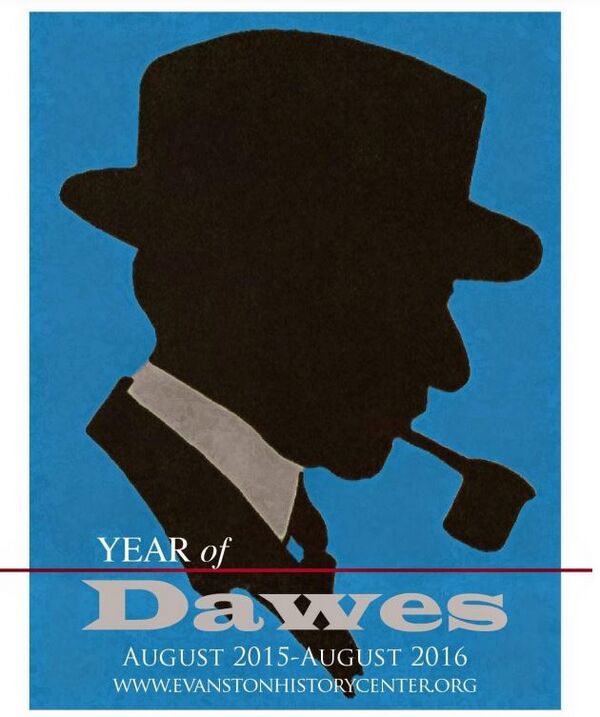

Indulge me as I present a few appropriate portraits, sketches, and photographs of the Honorable Charles Dawes. This one hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

In 1914, a formal portrait of General Dawes, painted by John Doctoroff, was donated to the Evanston History Center, Evanston, Illinois, and was to be hung in the Dawes House in Evanston, Illinois. The portrait depicted Dawes holding his famous pipe. When his wife Cora saw it, she demanded that the pipe be painted over and Doctoroff complied.

Much before the Lyon pipe was patented, General Dawes was known to be a steadfast pipe smoker who had also smoked Invincible Perfectos.

I want to explain the organization of what follows. The quotations are in chronological order as they appeared in the Press, rather than when a particular event involving Dawes and his pipe. First, I dispense with everything about the man, then everything about his trademark pipe. Because I chose this arrangement, organizationally, the sequence of some quotations may interrupt the narrative thread, but this could not be avoided.

When the visitors, of whom there were perhaps a hundred, filed into his simple office in the Treasury Building, they saw a small, well knit, nervously energetic man, fidgeting in the chair behind his desk; his brows contracted, his eyes studying the men before him with intense earnestness, while clouds of smoke rose in energetic spurts from the Algerian briar pipe which protruded from his mouth. Scarcely once during the interview did the general remove his pipe, in which he seemed to find a steadying influence during the most picturesque and perfervid flights of eloquence (“President Harding Praises Trade Press of America,” The Music Trades, April 22, 1922). As he [General Dawes] strode up and down the floor, launching his fulminations against divers and sundry ’woodenheads’ in official life, the doughty general emphasized his remarks by waving a peculiar looking pipe in the air. Interest expressed by newspaper men in the pipe at the time brought forth the promise that they would be furnished with some of the same make. …The pipes were received a few days ago. They are of a curious construction, with the bowl below the stem, and a spiral-shaped contraption within through which the smoke is filtered (“Odd Pipes Presented White House Correspondents,” The Fourth Estate, May 19, 1923).

“It [the film] gets applause everywhere, not because the General is a prominent figure, but because he looks like a ‘regular feller.’ His briar pipe pours out a cloud of smoke, leaving no question that he enjoys every puff” (“General Dawes on the Screen,” The United Shield, July 1924). “Men are smoking the ‘Hell and Maria’ pipe, as the low slung tobacco receptacle General Dawes adorns has been dubbed by the manufacturer…” (“Dawes a Central Figure,” Commercial West, August 23, 1924).

“Don’t Like the Dawes’s Pipe.” The Maine Republican committee got out a poster showing Gen. Dawes, candidate for vice-president, smoking his famous pipe. However, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union complained that it set a bad example for men and boys so it was withdrawn from public gaze” (The Pathfinder, September 6, 1924). “Toledo Blade—The Dawes success in Europe may result in the pipe of peace being smoked upside down hereafter” (“Newspaper Views,” September 27, 1924). Dawes had negotiated a plan to reorganize European finances in the wake of World War One.

At Sparta [Wisconsin], a woman called attention to his pipe. ‘That’s all right,’ she said, referring to his remarks, ‘but what about that pipe?’ and she leveled an accusing finger at his pipe, which was going full blast.’ ‘That’s not an affectation,’ said the General, it’s a bad habit, and I admit it. Now let me tell you about the women in this campaign.’ He did so. ‘That’s all right,’ said the woman, ‘but no pipe in a dry territory’ (“Dawes Pipe Draws Reproof of Woman,” The New York Times, September 28, 1924).

“Pipedom is fortunate. What with Vice-President Dawes and his underslung pipe, and the latest famous pipe devotee, Attorney-General John G. Sargent, pipes are in for a lot of free publicity during President Coolidge’s administration” (“From Various Sources,” The Bulletin of Pharmacy, January 1925).

The newly elected Vice-President, Charles G. Dawes, smokes a peculiar kind of pipe, and advantage has been taken of this to broadcast in every conceivable way the fact that he smokes. The odd shape of the pipe gives an ‘excuse’ for stating and restating the fact in various forms. Evidently Mr. Dawes himself is not proud of the habit. The ‘Tobacco Leaf’ says of him: ‘Newspaper photographers and motion picture camera operators, after aiming their cameras at him, invariably beseech him to replace between his teeth the pipe, which he invariably removes when about to pose for a photograph. There is some satisfaction to friends of the youth of the land in knowing that Mr. Dawes is sufficiently ashamed of the habit to remove his pipe when posing for a picture, until he is beseeched to place it again in his mouth (“Yes, He Uses Tobacco,” Industrial School Journal, February 1, 1925). “General Dawes, of course, has established two styles. One is in pipes, the other in collars. His pipe style is a success, an enormous success, for Dawes himself, and the trade. But his collar—Well, his collar always accompanies each picture of himself, naturally, and the Saturday Evening Post, recently published a picture of the Vice President with his pipe, and the caption, ‘The most famous pipe in the country,’” (“Dawes and Baldwin Fight for Supremacy of the Pipe,” Tobacco, May 14, 1925).

From a letter from A. D. Lasker to General Dawes (then working at Central Trust Co. of Illinois) on April 9, 1923: “I want to thank you for the pipe that reached me here. I have not been much of a pipe smoker up until now, but when I can tell my friends that I am smoking a pipe given to me by the greatest and most famous pipe smoker in America, there will be some class in that” (“Hearings,” United States Shipping Board and Emergency Fleet Corporation, Part 5, 1925).

This is an explanation of how the General became associated with the Dawes pipe.

How General Dawes first became acquainted with the trick pipe, and a brief history of its inventor is related here in part from an article in Chicago Commerce. Mr. H. C. Lyon is the inventor and manufacturer of the famous pipe. When General Dawes returned to Chicago from Washington after organizing the national budget, there appeared on the front cover of a magazine a photograph of the General holding in his hand an ordinary pipe. Mr. Lyon saw the picture. He was just perfecting his invention, so he sat down and wrote to General Dawes substantially as follows: ‘I have just been reading a magazine which contains a photograph of you holding a sapsucker in your hand. Under separate cover I am sending you a tobacco smoker. Smoke it for two weeks, and if you like it send me a check; if you don’t like it, don’t.’ Instead of a check for one pipe, Mr. Lyon received a remittance for thirteen. Since then General Dawes’ orders have averaged about a dozen a week. The story of the pipe itself is interesting. …While thus occupied one evening, an unusually long pull on the briar gave him a mouthful of ‘suds.’ ‘Why don’t someone invent a pipe that won’t do this,’ he said to himself. And then, ‘you’re a mechanic, why don’t you try it?’

In an hour’s time he had completed the first rough sketch of the pipe that General Dawes had made famous, had the paper dated, signed and witnessed, and the next day set about getting a patent. Then came several years of experimentation, the designing of machinery to make the pipe and ‘kicks a plenty’ from those who tried out the new idea. It is only in the last two months that this pipe has been perfected and has become, as Mr. Lyon says, ‘worthy of a man like General Dawes.’ The inner bowl of the trick pipe is made of French briar and the outer bowl of the roots of mountain mahogany, wild ivy and mountain laurel, all first cousins to French briar, or white heather, and found near Celo, N.C. It is claimed for the pipe that it embodies the principle of the steam separator, which removes the water from the steam and delivers it as a dry gas to the engine. Tobacco smoke contains water, light oil, a resinous gummy tar, ammonia, and a trace of nicotine. These are the condensible portions of tobacco smoke which Mr. Lyon calls sludge. What remains is a fixed gas, and that is what the smoker wants, according to the inventor (“The General and His Pipe,” The Bank Man, Vol. XX, No. 10, October, 1924).

The newspapers of this country had made much of General Dawes and his famous bottom-side-up pipe for weeks, and their articles and pictures of Dawes and his pipe had pipe smokers at the point where they were impatiently waiting for the pipe to appear in United stores and Agencies so they could buy it. Newspapers as a rule do not knowingly give any publicity to a commercial article except in the advertising columns, which must be paid for in real coin and at the formidable advertising rates. But in this case, because General Dawes and his pipe were inseparable, they unwittingly gave The General pipe the most effective free advertising that any article has received in a generation or more. As a result of the display shown here, plus the best salesmanship, this store sold 806 General pipes in 25 consecutive days, an average of 32 pipes a day (“This Display Produced Results,” The United Shield, September-October 1924).

“Shrewd observers have even declared that Dawes’s conspicuous addiction to tobacco, which has led him to design a special pipe, and his rough language have cost the party many a vote in old-fashioned American families” (“The Current of Opinion,” Current Opinion, October, 1924).

“A few months ago, General Charles G. Dawes blew in—I dislike this vulgarism, but the typical American obeying the best conventions of his kind always blows in—blew in the Ritz at Paris. After dining, he leaned back in his chair to discharge clouds of smoke from the most extraordinary pipe that Europe had ever seen. It was a vast engine for the consumption of tobacco with the stem coming out of the top instead of out of the bottom. And one does not puff at even the chastest of Dunhills in the Ritz dining-room. …All of Europe saw the pipe and made peace” (Clinton Wallace Gilbert, You Takes Your Choice, 1924). “Sometimes in a manufacturing industry a by-product becomes almost as valuable as the main article. …Which brings us to Gen, Dawes’s pipe, that looks upside down but isn’t. They admire the general very much over in Europe, and, naturally, when a man is admired he is imitated, at least in his most salient characteristics. That, with general, was his funny pipe. Now all Paris Is smoking pipes, and as Paris goes so goes France. The pipe of the author of the ‘Dawes plan’ is copied widely and enthusiastically as was the ‘imperial’ or pointed beard, of Napoleon III some 60 years ago. …It is only fair to add that former Premier Herriot and Premier Baldwin of Great Britain—pipe-pullers both—helped Gen. Dawes a little in bringing back the pipe to popularity” (“Gen. Dawes’s Pipe,” The Pathfinder, May 30, 1925).

I’m inclined to believe that Dawes was a one-man advertising billboard, a walking, talking, unintentional, yet successful, promoter of this uncommon pipe.

“So rapidly does Vice-President Dawes puff away at those peculiar pipes of his that he creates a tremendous back-draft and there has always been an imminent possibility of the General starting a fire in his collar or his shirt” (“Again General Dawes Scores With His Spark-Shield,” Tobacco, August 6, 1925).

A police escort, stiffly erect in fresh uniforms and white gloves, was waiting for him, but the policemen did not recognize him, and the Vice-President wandered into the waiting room of the railroad station, swinging his bag and puffing on his famous pipe. He dropped the bag and stood waiting for a moment, and was then recognized by a newspaper photographer, who said afterward that the pipe was more familiar than the Vice-President (“Reviewing Stand Was ‘For Firemen’”, Fire Service, October 24, 1925).

“It was further brought out that the market for ‘pipes’ had increased enormously in the last two or three months—the dealers not being able to meet the demand. Perhaps the Dawes episode has contributed something to this condition” (Thomas Medary Iden, Upper Room Letters from Many Lands, 1925).

“As he got off the train, General Dawes was fumbling with a worn, red tobacco pouch, striving to fill his big, queerly shaped pipe. By actual count, he smoked two pinches of tobacco and forty-three matches during the twenty minutes he was in New York” (Joseph Anthony and Woodman Morrison, eds., The Best News Stories of 1924, 1925). “Publicity made General Dawes a national figure. He remains a national figure so long as he and his pipe continue to fill newspaper columns” (George H. Sheldon, Advertising Elements and Principles, 1925).

An inaugural ode was written for him to be read on March 4, 1925, on the occasion of becoming Vice President. I cite portions:

Charles G. Dawes was a man of parts\Whose speeches brought renown;\He caught our eyes, he captured our hearts,\By smoking a pipe slung upside down—And, what is more,\He swore.\Sad is the fact—I shudder as I pen it—\All this means nothing to the U.S. Senate\He who fought across the ocean\Now must put the previous motion,\He must be a mere recorder,\ Bound by Roberts’ Rules of Order,\And his sword shall be beaten into a fountain pen,\His pipe into a gavel (Stoddard King, What the Queen Said and Further Facetious Fragments, 1926).

“There’s been a census of smokers and non-smokers in the President’s official family. …Hoover, Davis (War) and Sargent, like General Dawes, are addicted to the pipe” (Frederic William Wile, “What’s Doing in Washington,” The Farm Journal, April, 1926).

“Among them was Adjutant William Dawes, who with Paul Revere gave the alarm to the Middlesex Minute Men, and who is the direct ancestor of Vice-President Charles G. Dawes. ‘At their gatherings,’ wrote John Adams, ‘they smoke till you cannot see from one end of the garret to the other.’ He did not fail to add the fumes of his pipe. How congenial to our Vice-President the thought of that patriotic ‘smoker!” (Daniel Munro Wilson, Three Hundred Years of Quincy, 1625–1925, 1926).

“Marshal Foch, commander-in-chief of the allied armies during the world war, claims the distinction of converting Charles G. Dawes, then a brigadier-general in the A.E.F., to the use of a pipe. He told two Legionnaires today [September 27]: ‘I converted him. Now he has become such a fervent pipe-smoker that he has had special kinds of pipes made for him. He has sent me a number of them” (“Where That Dawes Pipe Came From Originally,” Tobacco, October 6, 1927).

“General Dawes grinned and puffed his hubblebubble pipe (christened by the British press ‘Old Underslung’). Edward of Wales tactfully produced a pipe from his own coattails, borrowed some of the Dawesian tobacco” (Time, “Foreign News: Canonibus Dawsiensis,” July 8, 1929).

“He took the famous ‘underslung’ pipe from his pocket and | began to fill it, smiling. There might be another General Dawes; his face might not be familiar; but everybody knows the underslung pipe of the popular Ambassador” (“London Topics,” The Sydney Morning Herald, October 25, 1929). “Puffing away at his underslung pipe, he went about his business at the capital as usual and chuckled over the tale” (“Plot to Kidnap Him Amuses Gen. Dawes,” The New York Times, January 24, 1932). “With his pipe, General Dawes can go through the motions of smoking without actually doing it, and so he doesn’t use up near as much tobacco as he otherwise would” (Ralph Alfred Habas, The Art of Self-Control, 1941).

“Hell ‘n’ Maria, an underslung pipe, and a refusal to wear knee breeches as an ambassador—these, if we may judge from the newspaper obituaries, seem to be the things for which General Charles G. Dawes will be remembered by the general public” (Don K. Price, “General Dawes and Executive Staff Work” Public Administrative Review, Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer, 1951). “General Dawes was a rambunctious, craggy-faced military man of the old school. An inveterate pipe smoker, he found the standard plumbing arrangement of briars both hazardous and often literally distasteful” (Men’s Wear, Vol. 153, 1966).

“In Paris, after the Armistice, Pershing once entered a room, whereupon Dawes brought everyone there to their feet with a rousing ‘Attention!’ in the best drill sergeant manner. Dawes felt rather proud of his performance and asked the general how he liked it. Pershing replied: ‘Well, it might have looked a little better if you’d taken your pipe out of your mouth’” (Donald Smythe, “John J. Pershing. A Study in Paradox,” Military Review, September 1969).

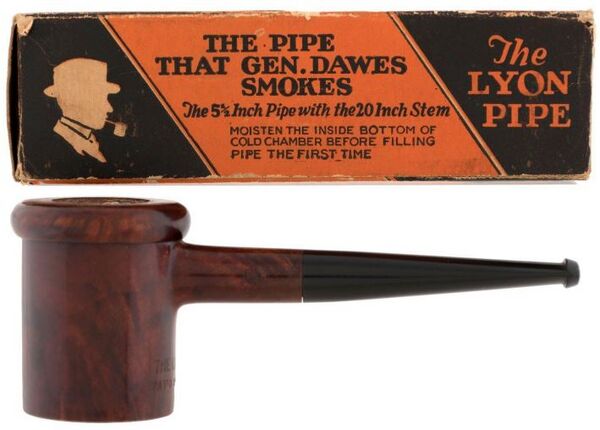

“The No-Tobacco League, headquartered in Indianapolis, achieved widespread membership. In 1925, the group made national headlines when it wired Vice President Dawes in Washington, D.C., and urged him to quit his pipe habit as a New Year’s resolution and set a good example for America’s youth. General Dawes whose underslung briar had become famous during the presidential campaign, responded to the telegram with a grin, described as ‘expansive but not responsive’” (Gerard S. Petrone, Tobacco Advertising. The Great Seduction, 1996). One of the English reporters eventually came to ask him about his peculiar underslung pipe. ‘Do you want to know now or later?’ Dawes asked, ‘because I assure you I am never going to mention this pipe more than once in England no matter how long I stay here.’ The reporter said he would like to know immediately. ‘Very well, then, said the ambassador, ‘I will now explain for the millionth and last time that this pipe catches all the liquid nicotine in the bottom so it cannot go through the stem and poison me. This is positively the last word on the pipe’ (Warren Sloat, 1929. America Before the Crash, 2004).

“When Vice President Charles Dawes revived the Christmas page dinner in 1925, the appreciative pages decided to turn the tables and offer their own gifts to the vice president. They delivered gifts to Dawes in a giant paper-mache pipe, a nod to his affinity for smoking a Lyon pipe (he became so identified with it that it became known after as a Dawes pipe)” (“Senate Stories/Christmas Giving in the Senate,” senate.gov, December 14, 2020).

“He was the only man who could smoke a pipe in the … White House and get away with it” (Annette B. Dunlap, Charles Gates Dawes. A Life, 2016).

Adding to his colorful personality, Dawes at this time adopted his trademark pipe. For years he had smoked as many as twenty cigars a day, but during the war a British officer had given him a pipe. Soon after his appointment to the Bureau of the Budget, a newspaper photograph showed him smoking his pipe on the Treasury Department steps. A Chicago pipe manufacturer sent him a new, strangely shaped pipe with most of its bowl below rather than above the stem. Dawes tried it, liked it, and ordered a gross more. From then on, he was rarely seen without this distinctive pipe, which together with his wing-tip collars and hair parted down the middle, reinforced his individualistic, iconoclastic, and idiosyncratic public image (yearofdawes.blogspot.com).

Where is one of his underslungs on exhibit? Tobacco (September 1, 1927) mentions that it is displayed in the museum at Rutgers University. And should you want to see him smoking it, watch this video clip, “US Vice President Charles Dawes, smoking a Lyon pipe” (gettyimages.dk).

The Dawes Pipe

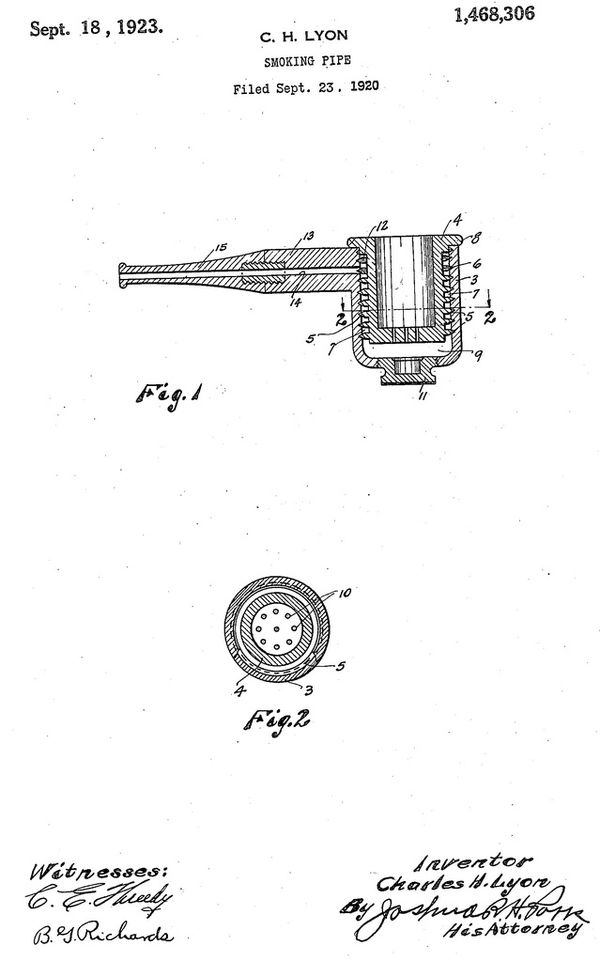

Rummaging around the Web, I found an ad in a trade journal for the Lyon Pipe, made by the Lyon Mfg. Co., 5911 South Kendzie Avenue, Chicago Illinois: “The Lyon Pipe with the Spiral Coil—$2. The Lyon Pipe separates smoke from sludge by gravity. All the sludge is deposited in chamber below. The smoke ascends through 20 inch coil to exit above. The Lyon Pipe smokes all the tobacco. No wet heel or dry throat. The same flavor, aroma and coolness from all the tobacco” (The Railroad Trainman, January 1921). This one must have been an early prototype that C. H. Lyon manufactured prior to the issue of U.S. Patent No. 1,468,306 on September 18, 1923. The U.S. Patent Office lists Charles H. Lyon of Chicago, Illinois, as having filed for this patent three years earlier, in September 1920.

The Lyon was introduced in 1924. “The Lyon pipe, now more commonly known as the Dawes pipe, was characterized by an inner bowl which was threaded into an outer bowl, with smoke traveling through the bottom of the inner bowl to reach the airway much as in a traditional gourd calabash” (“The Lyon Pipe,” pipedia.org). “Men are smoking the ‘Hell and Maria’ pipe, as the low slung tobacco receptacle General Dawes adorns has been dubbed by the manufacturer…” (“Commercial Banks Buy Commercial Paper at 3 Per Cent,” Commercial West, August 23, 1924). “In offering the Lyon Pipe at $1.50 to the smoker, the Kaufmann Brothers & Bondy house, of 33 East 17th street, New York, tell him to ‘smoke the pipe–not merely the shape!’” The Dawes was promoted as “The Pipe Sensation of the Age—Not a Passing Fad.” (Montgomery Ward & Co. catalogs of the mid-1920s advertised the “Genuine Lyon’s Pipe” at $1.29. Same shape as above, without special smoke circulating bowl, 85¢, while the Jordan Marsh Company of Boston sold it at the outrageous price of $2.50.)

The pipe that accidentally tied itself up with the forceful personality of an American smoker with original ideas and as a result became popular overnight. …Also, he smoked an unearthly-looking, underslung pipe that looked as though it was upside down. The pipe ‘caught on,’ and suddenly every American smoker wanted one of the same pattern. The General had always had his pipes made to order, because it was not a commercial size, so the smokers had to wait for the time being. Big pipe manufacturers, however, took up the idea quickly, and The General pipe broke all speed records in being put on the market. General Dawes has since become a Vice-Presidential nominee, which has added greatly to the prestige of the pipe. It is named The General, but the public has dubbed it ‘The Dawes,’ and the name will stick. Apart from the novelty of its introduction, it is a very practical pipe with several advantages over standard shapes. Its Bakelite inner bowl will not burn out and, being reinforced by the outer briar bowl, cannot be broken. The air space between the bottom of the Bakelite bowl and the intake of the stem, assures a cool smoke, for the smoke does not come direct from the heated bowl. This Bakelite bowl always keeps perfectly dry right down to the bottom form two reasons: First, because the sediment drops into the bottom of the briar bowl and, secondly, the stem being at the top, the smoker cannot force any moisture from his mouth through the stem into the bowl, The sediment is easily cleaned from the bottom of the briar bowl, but a better way is to keep a small piece of absorbent cotton or blotting paper in the bottom and replace it as it becomes saturated. In this way the outer bowl remains sweet and wholesome—a feature not possible in other pipes. …The practical features of The General take it out of the fad class and are bound to leave it with a big following after the Presidential campaign is over. But unquestionably the time to get it thoroughly introduced is right now, when it can get the added prestige which the name of a well-known candidate gives it. At a dollar it is exceptional value, being of fine quality briar and the best grade of Bakelite. The General can also be had in a $3.00 quality, packed in cloth bag in an individual box and with an aluminum cleaner (“The General Has Arrived,” The United Shield, September–October, 1924).

A placard was displayed in a Philadelphia tobacconist’s window of a poem written by N. D. Plume, “Ballad of Transformation. Smoke a HELL MARIA—THE DAWES PIPE,” The last line of each of the four stanzas is “I’m smoking a Hell Maria Pipe” (Life, October 30, 1924).

In the circuit riding window displays now being arranged by the United Cigar Stores Company for the General pipe, the title ‘Evolution’ is used appropriately in connection with a most complete showing of the processes of manufacture. This General underslung Dawes is a pure bakelite-made article. It is therefore exhibited, first in a simple log of wood. This wood is next shown as a lump of coal. Then, in turn, from coal to coal tar product, in a line of liquid containers, the bakelite is reproduced in the pipe molds, showing just how the General comes to life in a finished product, ready for the smoker” (“Evolution of the General Pipe is Complete,” Tobacco, June 11, 1925). For this is, of course, the very pipe, style, shape, and size that General Dawes made famous in France before he became Budget Boss and Vice President of the U.S.A” (“Smoke the Pipe—Not Merely the Shape!”, Tobacco, March 5, 1925). There was also a bent-stem configuration. “The Bent Lyon. The bent stem is the only difference between this pipe and the original Lyon—'The Pipe General Dawes Smokes.’ …The Bent Lyon, priced to retail at $1.50 will easily be your biggest seller (“Pipes Carved and Curved Have the Call Right Now,” Tobacco, May 7, 1925).

“Ques: How is the Dawes pipe made?—Ans. The pipe popularized by General Dawes is ‘underswung.’ The stem enters the bowl near the top, giving the pipe the appearance of being upside down. Usually this type of pipe consists of two bowls, an outer and an inner. The holes in the inner bowl are in the bottom, thus giving a bottom ‘draw’ like an ordinary pipe” (“General Dawes’s Pipe,” The Pathfinder, July 18, 1925).

Not helpful at all is this from picclick.com: “B&B/KAYWOODIE called it ‘THE LYON PIPE’ while many collectors call it either a ‘CAPTAIN WARREN’ or ‘GENERAL DAWES’—and there are good reasons behind each of these names!” The good reasons are not stated.

As an aside, the Dawes pipe inspired a design for an artificial larynx. “More than anything else, the little device resembles the new inverted pipes smoked into popularity by General Dawes” (“Western Electric Supplies Dumb With Voices,” Western Electric, January 1925).

With the public it is partly the case of good sales talks by men behind United counters and also our educational system of pipe widow cards, such as shown here of ‘The General,’ which tell the tale in a few words. Many people were of the opinion that ‘The General’ pipe was a fad that would last only as long as the national presidential campaign. But like General Dawes himself, there is something substantial behind the pipe to give it permanency in the pipe traffic, and today finds it in greater demand than ever before. It is substantial, stands an unusual amount of rough usage, can be kept clean all the time, and its bakelite bowl neither heats up unduly, cracks or burns out. It is the best cool-smoke pipe made and tobacco always tastes sweet and nutty in it. In pursuing the pipe campaign to double your pipe business, do not overlook the merits of The General—it is one of your best pipe bets (“Pipe Window Card for the General” (The United Shield, Vol. XXII, July, 1925).

“Of course there is the ‘Hell and Maria’ pipe made famous by Gen. Dawes. The underslung model is more than a mere oddity. Inside the bowl is an inner bowl which unscrews. These pipes insure [sic] a cooler smoke since the smoke travels through the grooves between the two bowls before it reaches the stem. The smoke goes through twenty inches before it reaches the smoker’s mouth” (Rachel Lamprecht, “Choose Your Pipe to Fit Your Dream!”, The Santa Fe Magazine, May 1933).

“Dawes’s trademark pipe was an unusual shape, evoking iconic images of Sherlock Holmes, with most of the pipe’s bowl sitting below the stem” (Dunlap, op. cit.).

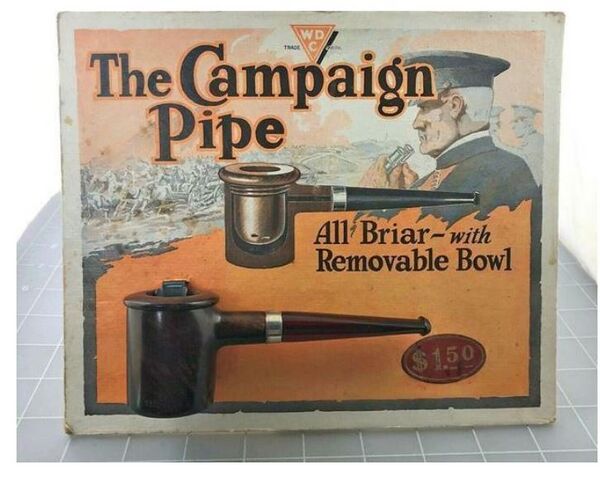

The Campaign Pipe is WDC’s version of the General Dawes.

I suggest that you read two posts on pipesmagazine.com: Seacaptain: “Coolidge, Dawes, and the Lyon Pipe in the 1924 Campaign,” and a fascinating bit of history told by kingbilliard, “Pipes that made history: lesson #2,” an account about John Dillinger and Dawes.

The Captain Warren

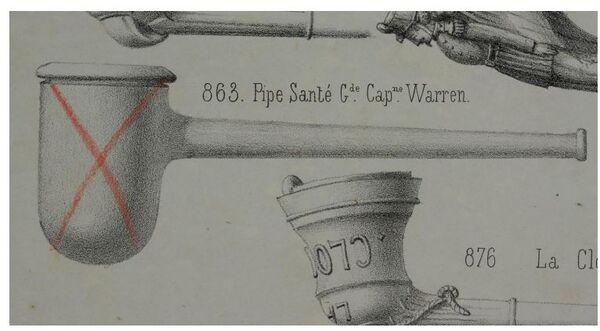

This is Model 863 in the Gisclon clay pipe factory catalog, Lille, France, c. 1870s; Pipe Santé means “health pipe.”

If the Pipe Santé G.de Cap.ne Warren was a production pipe in the late 1800s, it would suggest that the Captain Warren pipe was a French design. But why would a French clay pipe maker assign an English name to one of his pipe designs? Could this pipe be the very first Captain Warren? Unfortunately, I found no other illustration of a French clay pipe in this shape and of that timeframe. Consider, though, that that the Captain Warren briars from Adolph Frankau & Co. were described as “Health” briars in its Catalogue, No. XX 1912.

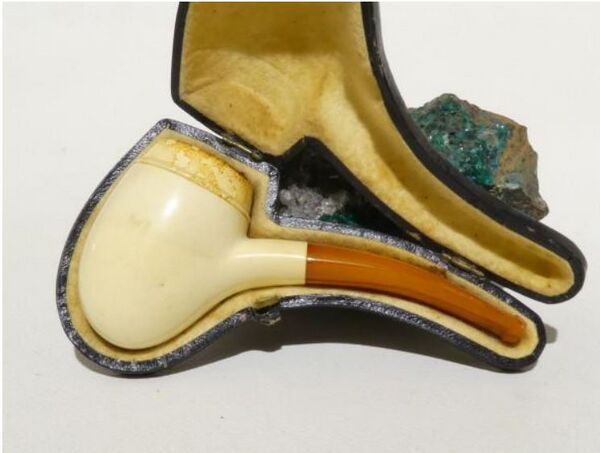

Next, I include this image from London’s Science Museum: “Briar tobacco pipe bowl only with detachable clay filter bowl, Captain Warren’s Filter, English, 1880–1925”?

Unfortunately, the body of the pipe is missing, but if this inner bowl is an accurate provenance, then there’s some evidence that a British Captain Warren briar pipe preceded the production of the Lyon pipe by many years. As advertised in London’s The Sphere. An Illustrated Newspaper for the Home in the early 1900s, the little-known Patent “Urn” Pipe was quite similar in design to the Captain Warren. What is not common knowledge is that a French clay pipe may have been the inspiration for the British Captain Warren.

“The Captain Warren pipe line is inspired by the Nordic custom of creating a double chimney pipe. Original project by Leonardo Da Vinci” [tabaccheriatoto13.com]. And from a pipesmagazine blog on the Ser Jacobo Leonardo pipe, I excerpt the following: “In 1982 Professor Enrico Fabri discovered a four page document which contained several inventions which seemed like something created by Leonardo da Vinci. … Leonardo da Vinci devised a twin-walled terracotta pipe which was cooled by the air circulating in the cavity.” I consider both statements rather far-fetched assertions. Although neither comment suggests that the Captain Warren is descended from a 16th–Century da Vinci clay pipe, the connection is dubious.

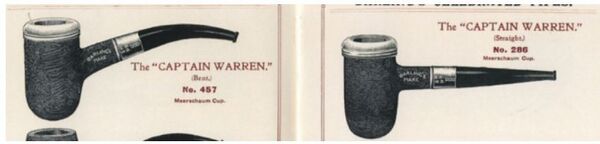

These two Captain Warrens are from an early Barling catalog.

In the early 1900s, K&P made the Captain Warren called the “Fiscal” pipe. Loewè’s Illustrated Price List and Catalogue (1910) includes the “Capt. Warren,” and here’s a 1907 edition from Benson & Hedges.

In the 1960s, BBB manufactured Model No. 1503, “The Warren Drysmoker.” I found no Captain Warrens in Dunhill’s About Smoke (1928), but this Dunhill, stamped “Pat No 116989/1712, shape number “28,” is a General Dawes, and misidentified as a Captain Warren. (I’ve notified the website.)

And, in that same era, the Captain Warren was popular enough that it was also produced in meerschaum by several British pipe factories.

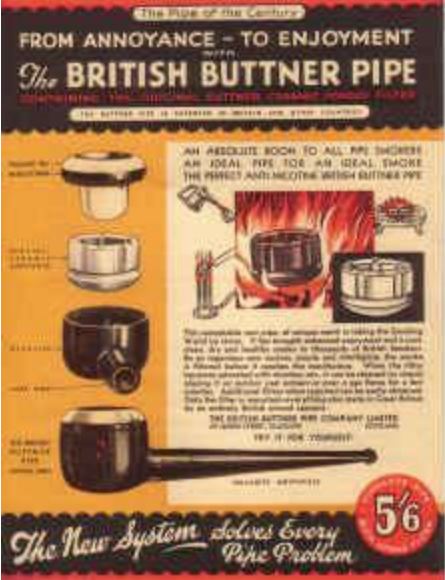

Sometime in the 1930s, the British Buttner Pipe Company of Glasgow introduced its system pipe. Was it a revival of a sort of Captain Warren-like Bakelite pipe that “solves every pipe problem”? One could conclude that the Brits were more enamored with this shape than our American pipe factories, but I have no solid evidence to make this assertion.

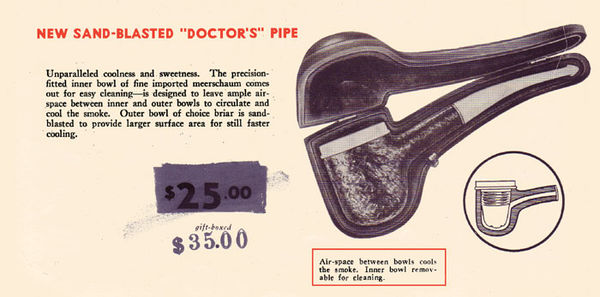

Here’s an interesting comparison. Frankau had its Captain Warren “Health” pipe, and this is a 1950s Kaywoodie Doctor’s pipe. (It sure looks like a Captain Warren!)

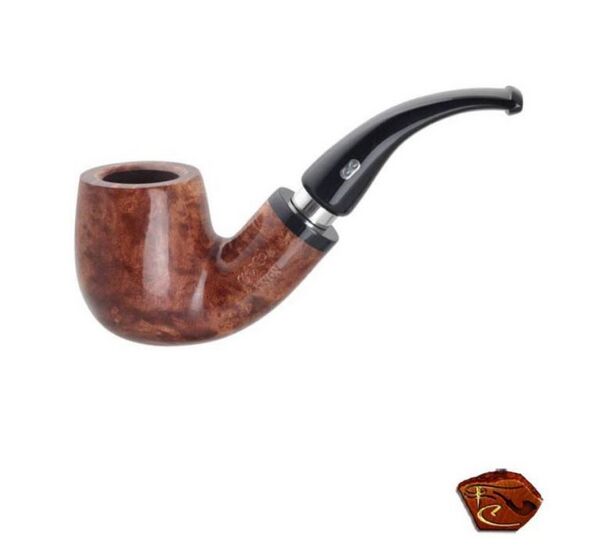

Today’s Expressions

As this narrative indicates, the Dawes eventually fell out of favor and became a here-today-gone-tomorrow pipe format. Conversely, very little attention was given to the Captain Warren pipe in almost the entire 20th Century. How ironic that, today, it is alive and well. Cavicchi, Paronelli, Viprati, and others are crafting their own variations. There’s a very authentic Savinelli estate Captain Warren on offer at Smoker’s Haven. It is not my style to openly criticize smokingpipes.com, but I am surprised to read this: “Captain Warren Sandblasted Cherrywood (S2) Tobacco Pipe. Crafted 20 years ago, this novel briar is known as the Captain Warren, but it’s also, over the years, been known as the Lyon pipe, the Dawes pipe, or simply, the General” (smokingpipes.com). And this: the “Ser Jacopo: Captain Warren Smooth Cherrywood (L1)” (smokingpipes.com) that exhibits a very flat bottom. There are variants, of course, such as “Ser Jacopo: Historica Spongia Capt Warren Sandblasted Bent Egg Calabash (11) (S3Tobacco Pipe)” from smokingpipes.com.

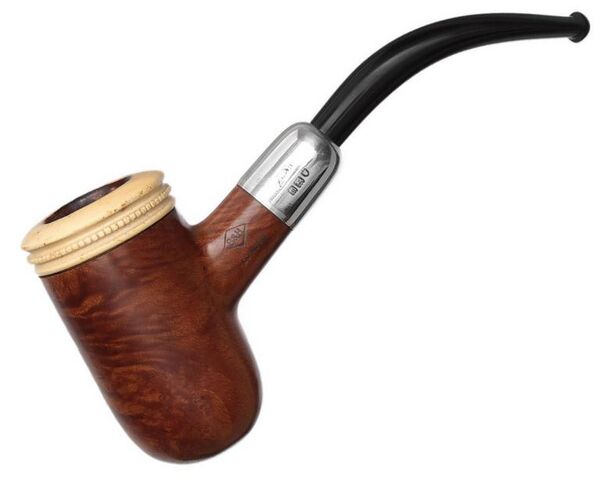

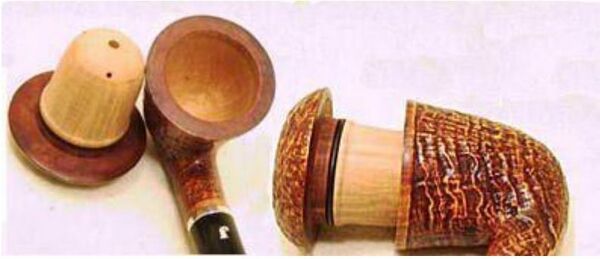

This is a Ser Jacopo Captain Warren disassembled.

The Chacom’s Lyon No 41 pipe is something else altogether.

Summary

What I have established, based on overwhelming evidence, is that no other pipe smoker in the last 100 or so years, here or abroad, was as much in the public eye as General Dawes, the two-fisted captain of industry, “the man of the underslung pipe and the colorful speech who was unafraid,” the no-nonsense Vice President. This is the quote from his official biography: “Together with the pipe and centrally parted hair, this idiosyncratic collar signifies in Dawes a man who delighted in ignoring tradition and cutting through red tape in search of efficiency” (govinfo.gov). And no other briar pipe in recorded history has ever received as much Press as the General Dawes. As mentioned previously, hardly anyone is making the General Dawes today, but there certainly is a revival of the Captain Warren by both factories and artisan pipe makers. Does it seem counterintuitive?

The General Dawes pipe has provenance, the Captain Warren does not. The Dawes was a patented pipe. There is no record of a patent for the Captain Warren pipe. General Dawes was a real person. Wherever I searched, just about every mention was Captain (No First Name) Warren. “Captain Warren’s honorable name has already received the promised fame” (The Provi, June 1922). “Captain Warren has a title, so he doesn’t need a first name” (Abdulhamit Arvas et al., Critical Confessions, 2023). I had hoped to find his first name! However, an examination of all the available sources, the historical evidence that people left behind, yielded nothing meaningful.

Was this Warren meant to be anonymous, fictitious, contrived? If he lived between, say, 1875 and 1930, he might have been a pipe-smoking skipper or perhaps the Tommy buried in Westminster Abbey’s Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. Or maybe it’s a mistaken identity, that Warren was his first, not his last, name. Without a first name, we may never know who he was and why he is affiliated with this pipe. It’ll remain a mystery inside an enigma. Does it matter? Well, it depends on how interested you are to know the provenance of this pipe. Was it that late 19th-Century, French Captain Warren clay pipe or the early 20th-Century British briar?

As a pipe historian I was interested in the discovery—I still am—but I have little hope for an “Aha!” moment.

And last, reader, consider that in the chain of command of every military organization, a general outranks a captain…even a Navy captain.