A Magical Mystery Tour: Meerschaum, the Queen (or King) of Tobacco Pipes

Exclusive to Pipedia

The Magical Mystery Tour was a Beatles album that was released in 1967. According to the Collins Dictionary, in British English it means “something exciting and mysterious; especially an exploration of a new place where somebody being shown or taken around does not know where exactly they will be going.” I want to take the reader on a magical mystery tour of antique meerschaum pipes. Meerschaum, the German word for sea foam, is hydrous magnesium silicate, a white, claylike, malleable, porous substance with the chemical formula Mg4Si6O15(OH)2·6H2O, 2H202Mg03Si02. The purest form of this mineral is found 30 to 450 feet below ground in mines around Eskişehir, Turkey, now the principal center of meerschaum pipe-carving and finished pipe export.

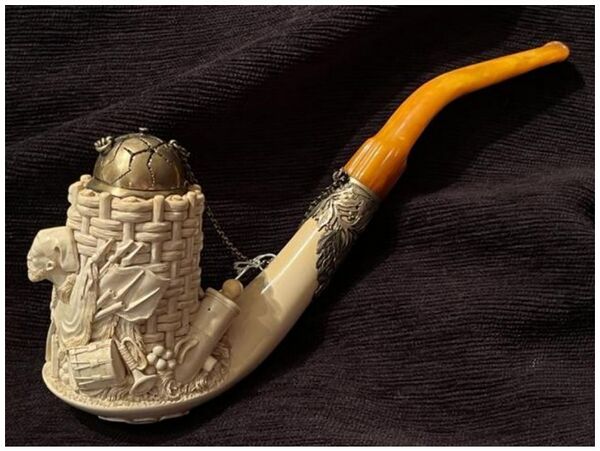

Meerschaum carving began as a cottage industry in Pesth (later Budapest), Hungary, in the first half of the 18th century and it spread west across Europe to Vienna, Nuremberg, Ruhla, Paris, London and, eventually, to the United States. Ateliers engaged graduates of academies (typically trained in art history, painting, material analysis and the technical science of stone, clay and Plaster of Paris), alongside journeymen and apprentices to learn the trade and how to use special-purpose, handmade tools. Early on, the most remunerative work for a sculptor was carving meerschaum. Myriad nameless artisans collaborated with the craftsmen of related guilds: jewelers, metal smiths, wood turners and those who made pipe stems, mouthpieces, and assorted other pipe fittings to produce a finished pipe ready for sale.

The meerschaum pipe had its competitors that were in popular use in the early 19th century. These were the utilitarian, plain clay; the moulded porcelain pipe bowl with little to no décor and a stem most often of cherrywood; and bas-relief-carved wood pipes. Briar was introduced in the latter half of the century as factory-made pipes in simple formats. All these mediums fit the practical requirements of form, fit and function, but the meerschaum was the ideal medium, because it absorbed the tars, oils, and nicotine in tobacco, allowing for a cool, dry, unparalleled smoke. More significant was that the meerschaums of that era were otherworldly in their craftsmanship and beauty. The mineral could be carved, sculpted, incised, and etched into bas- and high-relief pipes, cheroot (cigar) holders, and cigarette holders … hand-held masterpieces, marvels of workmanship. When the bowl was joined with a turned amber mouthpiece, the pipe became more than just another utensil to hold tobacco; it became a combination of alchemy and art. The meerschaum earned the title “queen of pipes,” as well as “king of pipes.” “The German pipe is the most important for the art workmanship it occasionally exhibits; and the Meerschaum is the king of European articles of the kind” (“The Meerschaum Pipe,” Morton’s Sixpenny Almanack and Diary, 1876). Whether queen or king, the meerschaum reigned for some 75 years unchallenged and uncontested.

There’s an uncorroborated story—more industry legend or collector folklore than fact-based history—that, around 1720, a certain Count Andrássy of Hungary gave a chunk of crude meerschaum to a local cobbler and wood carver, Károly Kovács, and was to have said to him: “Make, fellow, something pretty out of this.” Writing about the few meerschaum pipes exhibited at London’s Great Exhibition in 1851 in The London Journal in 1862 (“A Few Words About Tobacco Pipes”): “All that is requisite for us to inform our readers … is that all these pipes are made of the best and most precious, or, at least, the most esteemed material of which pipes can be made—meerschaum.” This was the mantra for meerschaum pipe carvers across Europe and in the United States for about the next 200 years!

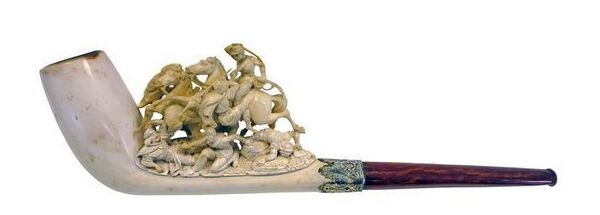

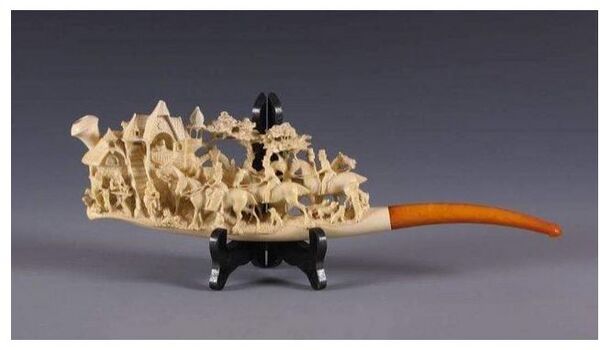

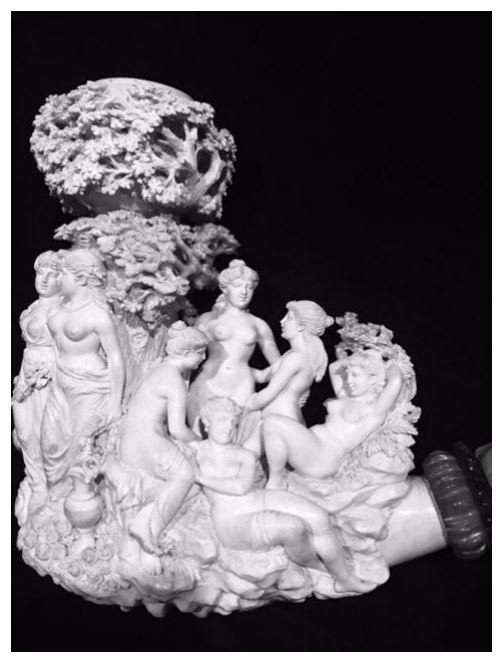

The carver’s imagination ran wild, and pipes of incomparable creativity and beauty were produced. Almost any motif one can name was expressed in this medium, the articulation of dramatic imagery in one-of-a-kind pieces as miniature, architectural statements that summoned all the magic and mystique of diminutive works of art. The range and breadth of selection in that day was extraordinary in subject matter, size, shape, ornamentation, and décor, each pipe different, one from another. Each represented an unusual and rare message, each intricate, fascinating, and unusual; often, the challenge was to determine the impulse of the carver, because each creation was a life-like representation of personalities, events, animals, landmarks, erotica and more. Literature, paintings, and opera, artists, and composers, respectively, were opportune motifs for the carver. As I wrote in Collecting Antique Meerschaum Pipes. Miniature to Majestic Sculpture 1850-1925 (1999): “Inspiration and ideas came from everywhere: victory and defeat in battle; the hunt; the birth, marriage, and death of royalty; mythology; heroes and heroines; and everyday life.” Anna Ridovics, a curator specializing in antique pipe history at the National Museum of Hungary, Budapest, contends that to carve meerschaum required erudition in the applied arts, that old-school, carved meerschaums were masterpieces comparable to the larger-than-life creations in bronze, marble, alabaster, and stone of Brancusi, Cellini, Mailliol, Moore, and Saint-Gaudens. Others have described meerschaum pipes of that era as “perfect gems of art.”

And the pipes found in a 19th century tobacco shoppe? Victor Tissot (Unknown Hungary, 1881) explained:

“The tobacco shops display in the windows a whole museum of attractive subjects; sleeping Venuses, fainting Ledas, sirens who, if more modern, are not more clothed; rosy Cupids, spitted on amber needles like large butterflies or moths; next, spread out fan-shape, are heads of heidukes with ferocious moustaches sculptured in meerschaum with unparalleled skill; heads of negroes and of gypsies in hats, the top taken out—for these, as well as the busts of sirens and amazons with high hats, are destined to hold cigars and cigarettes; serpents in coils, doves billing and cooing; all the products of an art almost unknown among us, but which is developed here in this wonderful carving in meerschaum for the benefit of smokers, and for those who watch them colouring these carved goddesses.”

Forty years ago, a visitor to any of three American tobacco and pipe emporiums would have had a similar visual experience as Tissot. D. P. Ehrlich, Boston, Bertram’s, Washington, D.C., and Iwan Ries & Co., Chicago, had a large array of antique meerschaum pipes on exhibit. Astley’s in London had its exhibit of antique meerschaums to behold. Sadly, these collections have been dispersed. The only American museum devoted to this art form, the Museum of Tobacco Art and History, Nashville, Tennessee, closed about 25 years ago. Most tobacco museums in Europe have shuttered, but one, the Amsterdam Pipe Museum that is accessible online.

With the end of World War One and a more cosmopolitan life, smokers preferred smooth, geometrically-shaped pipes that gradually replaced carved ones that were unfit for modern life, and carvers responded accordingly. As well, the early years of the 20th century saw not only a decline in interest in smoking meerschaums, but also the passing of many carvers with no follow-on generation to continue the trade. Today, Turkey is known for its elaborately carved meerschaum pipes, and has brought the art form back to life, but the carving, in my view, is not even a good imitation; their pipes do not compare favorably in detail and finesse with their predecessors. In their defense, I acknowledge that the Turkish carvers of yesterday and today never were exposed to formal schooling and apprenticeship as were the Austrians and Germans. Their skills, I have to say, are the result of artistic intuition and aptitude.

As promised, here’s a magical—but rather limited—visual tour into the world of the meerschaum pipe in the mid- to late 19th century with three images from three collectors. These offer an insight into the talent, skill, and dexterity of so many who plied this trade.

Antique pipe collecting is not a new phenomenon. It dates to the mid-1700s–mid 1800s with some rich and famous personages: Pierre Lorillard (Lorillard Tobacco), Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis (The Duc of Richelieu), Prince Augustus Frederick (the Duke of Sussex), The Iron Chancellor Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria, and Baroness Alice de Rothschild. In the 20th century, three notable collectors were the English pipe manufacturer Alfred Dunhill and William Bragge who had amassed a global collection of some 7,000 smoking utensils, and King Farouk of Egypt and the Sudan who collected erotic and pornographic meerschaums.

What is the price of admission to this hobby? When asked about the value of antique meerschaum pipes in 1998, the late pipe collector Frank Burla said: “Museum-grade antique meerschaum pipes go for $2,000 to $10,000.” (Auction houses normally avoid using the term “museum-grade.”) Years later, Burla changed his opinion: “Prices for antique pipes can range from $50 to $100,000.” More realistically, “As with many antiques, a meerschaum pipe is worth what someone will pay for it. They can be found on Internet auction sites from $50 to $1,500” (Jean Rabe, “Estimated Value of Used Meerschaum Pipes,” ourpastimes.com).

To gauge current-market prices, I cite two noteworthy pipe auctions. In February 2018, Locati, Maple Glen, Pennsylvania, sold the Arno Ziesnitz meerschaum pipe collection (invaluable.com); some 5,000 bidders from 70 countries registered for this auction. One meerschaum depicting “monumental classical figures” sold for $4,600. The second auction was Piguet, Geneva, Switzerland (Vente de Décembre 2020), on December 8, 2020. Of the 55 extraordinary lots of meerschaum and ivory pipes, most exceeded House estimates, and several sold for much more than $10,000. In defense of the exceptionally high prices at this auction, I would note that these were rarities in near-mint condition; several had exacting provenance; and, most important, although the community of collectors is gradually thinning, it’s rare when a substantial quantity of desirable antique meerschaums appears at the auction block. These pipes were not what one customarily would find on eBay, at a flea market, or at a vetted, antiques show. As Fodor’s London 2009 contends: meerschaum pipes “…won’t bust your baggage allowance but may empty your bank account.” Finely-carved meerschaums can still be bought at much less than $500.

Collecting is a hobby that gives enormous pleasure, provides intellectual stimulation, builds a desire for knowledge … and stimulates the thrill of the chase. Harry Rinker (Warman’s Antiques and Their Prices, 1987) declared that collecting antique pipes is “…an amorphous, maligned, and misunderstood hobby.” Quite true, and it is not for the faint of (financial) heart. However, it is ideally suited to anyone who enjoys owning things from the past that were once ubiquitous and unusual, functional and fanciful, manly and majestic. Antique meerschaum pipes fit this exact description.

For more about the queen of pipes and her consort, read these online articles, “Collecting Antique Meerschaums—Really Regal Pipes!” (September 2014, go-star.com); “The Antique Tobacco Pipe: Invention ● Function ● Art” (journal of antiques.com, 2019); and “The Metamorphosis of Antique Tobacco Pipes” (November 2, 2021, antiquetrader.com).