A Salmagundi of Briar Pipe Shapes and Names

Exclusive to pipedia.org

Introduction

American sports columnist and short-story writer Ring Lardner was best known for his satirical writings. I found his misspelled—on purpose—comment an apropos introduction to this narrative. “But in writeing this article I will half to raise the veil of secrecy in regards to some of my most intimate details which I ask the readers indulgents in advance for same” (Ron Rapoport, “Some Cigars Would Cure Any Smoker,” The Lost Journalism of Ring Lardner, 2017).

I now ask for your indulgence. Four years ago, “My Manifesto: A Plea for Plain Talk” appeared on pipedia.org, and I am still beating the drum against florid and complicated pipe and tobacco terminology. I am not alone in my plaint about the recent adoption of some peculiar terms that have entered our lexicon. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Juliet asks “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” The play was supposedly written in 1597. In 2023, I ask: “What’s in a name? That which we call a (fill in a pipe shape) by any other name would mean the same.” Oh, would that it were true today!

Have you ever considered some pipe-shape names to be abstruse, laughable, ridiculous? Does it often boggle your mind? Assuming that you are a Peterson “Thinking Man” pipe-smoker, you probably have encountered a few odd ones. Consider this, written 150 years ago: “Definitions are explanations of terms by means of other terms, the meanings of which are understood” (John Weale, Rudimentary Dictionary of Terms Used in Architecture, 1873). How pipe shapes got their names is a Shakespearean phenomenon … it’s a “rose by any other name” enigma. As I see it, through time, our pipe lexicon has gradually transitioned from unambiguous terminology and taxonomy to a frivolous—I’ll add often barmy, incomprehensible and borderline absurd—salmagundi of neological onomastics, mistaken metonymy or, perhaps, symbolic or metaphoric anthropomorphism. (I have purposely chosen these rarified words to emphasize my point.) This rather recent phenomenon is not an improvement to our customary usage, but rather an unnecessary obfuscation of, and an impediment to, embracing literal and comprehensible descriptions.

Following “My Manifesto” and “How Did The Pipe Get Its Name” (pipedia.org), this is Part Three, about tobacco pipe shapes and their names … my venture into seeking clarity out of what is often a confusing cornucopia of cognomens. I hope to unravel this whodunit by researching the record and sussing out the branding methodology of pipe shapes and their names, the logic of their assignment, how a word that means something entirely different now describes a pipe shape, and how some of these colorful pipe names became our lingua franca.

The question, reader, is whether this think piece will be a worthwhile investment of your time to read, and whether it sheds any new light on this narrow aspect of the pipe that you may not have previously considered or cared about. It’s probably not an interesting exposition for those who, using an analogy, have a favorite restaurant but would rather not know what goes on in the kitchen. As we are taught by Ecclesiastes 3:7: “There is a time to keep silent and a time to speak,” and so I speak … now.

Background

New pipe formats and shapes, including some outré, unconventional, avant-garde, and extravagant, continue to enter the marketplace almost daily with new names coined for them. As Pagan posted on pipesmagazine.com: “Just like tropical storms, new pipe gets the next name on the list.” When you’ve done enough reading and writing about pipes, it becomes apparent that we tend to gravitate to, adopt, and use words that often do not precisely describe our intent; more directly, sometimes the words assigned to describe a particular pipe format or design component don’t quite match its visual intent, yet we are predisposed to accept these terms de rigueur without challenge. Confucius understood: “Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.” “Ever since Adam assigned names to all the animals, we human beings have managed to come up with labels for almost everything on this planet—and beyond (Richard Lederer, Word Wizard, 2007). “Many of these names [of animals] are so obscure that no one except dictionary editors knows them” (Erin McKean, Totally Weird and Wonderful Words, 2006). She’s right, considering that a koala bear looks nothing like a bear, Panama hats originated in Ecuador, and head cheese is a meat product.

The issue is more than about semantic differences. In a February 12, 2002 news briefing about the lack of evidence linking Iraq with weapons of mass destruction, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld stated: “There are known knowns, things we know that we know; and there are known unknowns, things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns, things we do not know we don’t know.” Today, we know that there are many pipes with well-established shape names. But there are several known unknowns, such as: (1) where and when did this idea to give names to pipe shapes begin; (2) who assigned these names; (3) why are many of these pipe names misleading; and (4) why are they accepted as being descriptive of their visual pipe shape.

There is a science to pipe smoking, so we should be exact and specific in our terminology. Sometimes, history helps to address a knotty issue, such as this famous political question. During the Reagan’s Watergate scandal, Senator Howard Baker asked: “What did he [President Nixon] know, and when did he know it?” Later, the question slightly changed to “What do we know, and when did we know it” during the Iran-Contra scandal. What do we know about pipe-shape names and when did we know it? My answer: “We know very little, and we don’t know when.”

Here are some things we do know and accept. “The name ‘Lovat’ was most likely originated as a tribute to Lord Lovat, a title given in the Peerage of Scotland. This title originated in the early 15th century and continues with descendants of the original title holders today” (tobaccopipes.com). Here’s a more granular comment: “The Lovat is named after Lord Lovat-Fraser, Brigadier-General Simon Joseph Fraser, 14th Lord Lovat and 3rd Baron Lovat KT, GCVO, KCMG, CB, DSO (1871–1933), a leading Roman Catholic aristocrat, landowner, soldier, politician and the 23rd Chief of the Scottish Clan Fraser” (Eulenburg, brothersofbriar.com).

Most agree that the Prince is named after King Edward VII, former Prince of Wales. “The Prince pipe shape is also called Prince of Wales. Indeed, it is believed that it was invented by Prince Albert (Edouard VII) of England” (pipeshop-saintclaude.com). In 1921, Prince Edward granted Alfred Dunhill a Royal Warrant that granted him the right—but not exclusive—to use the Royal Arms. making him a grantee to the Royal Household. “In 1921 the firm [Dunhill] was granted its first Royal Warrant, as Tobacconist to Edward, Prince of Wales” (Alfred Dunhill, The Pipe Book). “In contrary to common belief the prince shape was not designed by Dunhill, but by Loewe & Co” (dutchpipesmoker.com). Funny that a 1926 ad illustrates His Royal Highness smoking a Sasieni pipe. The Dublin after the town bearing its name, and the Oom Paul after Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger of South Africa. However, the Canadian has no kinship to the country, and neither has the Belge/Belgique.

Some posit that the opera shape was originally an au pair or, perhaps, a rodeo pipe shape. Are you familiar with K&P’s kaffir (or horn) pipe from the early 1900s? Evidently, K&P did not know that kaffir was an ethnic slur, a reference to Black people; Kaffir is an offensive, racial term. (Shame on Peterson for having produced the “Kaffir” B35, one of its 2009 Antique Collection; much later, its name morphed onto a Bent Albert, a Zulu, a Woodstock, or a Yacht/Yachtsman.)

That’s just the tip of the pipeberg. I begin this investigation with two vignettes about the term “pipe types.”

“Studying any exhibition of the pipes of all peoples of all times, we can realize that the laws of evolution have been operative in their development. Innumerable designs have been selected for use. The materials used in their making have also been numerous. Today we find that popular pipes have been reduced to several well-marked types. The briar and the clay pipes are found among the best. The latest tendency is toward a short, light briar with light hard-rubber or similar tip and a bowl of large tobacco capacity. But judging from the long streams of patent applications for new pipe designs regularly flowing from the world’s patent offices, public opinion has not yet established a universal pipe type” (Dr. Arthur Selwyn Brown, “All Mankind Feels the Inspirational Charms of the Tobacco Pipe,” Tobacco, August 19, 1926). “Although authors sometimes identified what they called ‘types’ in their respective collections, there was no generally accepted classification scheme for use across sites, as with the ‘type-variety’ system. …The literature on classification is often written in terms of ‘types’ and ‘typologies.’ And yet ‘type’ has a very narrow meaning in archaeology. Some of the entities and concepts identified as ‘types’ in local pipe studies are a different kind of thing entirely: descriptions; analytical groupings; naming systems; or identification keys. (Anna S. Agbe-Davies, Tobacco, Pipes, and Race in Colonial Virginia. Little Tubes of Mighty Power, 2015). (Little tube of mighty power is the first line of an anonymously written poem, “Ode to a Tobacco-Pipe.”)

Sadly, the search of “pipe types” did not yield anything significant. In particular, the second quotation is archaeological, ethnographic, and demographic, not industry, research.

Now to “pipe shapes.” One of the challenges I experienced was the liberal use of alternate words for “pipe shape” in the Press and in ads. As well, ads from that era did not always use the most appropriate words to promote a brand. Many of the descriptive terms are not synonymous with the word shape, which brings me to explain how I treat shape in this narrative: literally, rigorously, precisely, without interpretation. (Some readers may conclude that this inflexibility reduces the scope and colors the substance of this article … that it’s mere hairsplitting, an unnecessary academic exercise.) Shape is as the dictionary defines it: appearance, configuration, structure, etc. Everything we see in the world around us has a shape. To shape is to give something a shape, outline and definition, and style is to create or give a style, fashion or image. This is a dictionary definition of style: “A particular manner or technique by which something is done, created, or performed.” Shape and style were and are still often used interchangeably. Model, type, form, and design, also used in old ads, are not exactly synonyms for shape. The French have a phrase, le mot juste, the right word, connotationally correct, temporally appropriate, and specific. It’s also about context, e.g., how was pipe shape and pipe-shape name used in the text. As you read further, consider the following, because it sets the tone for this discourse. Naming is describing, identifying, detailing, defining. Giving something a name makes it real as well as something that can be communicated. The name can be distinctive, but it should also be understandable.

(Plumbing pipes, by the way, is a science with universally understood and accepted definitions, types, shapes, and names.)

I often use analogies in my stories to advance a complex topic, and this topic is complex. I am reminded of Miquel Brown’s 1983 hit, “So Many Men, So Little Time.” Quoting Jeremy Hillary Boob, PhD, the Nowhere Man, in the movie, Yellow Submarine: “So little time! So much to know.” Or Peter Stead’s biography, Richard Burton. So Much, So Little. So many shapes, so many shape names, so little explanation!

A Brief History

Clay Pipes

“Now, you all know the shape of a tobacco pipe; it has a bowl to hold the burning tobacco, and a long handle up which the smoke is drawn into the mouth” (Isaac Taylor, Scenes of Wealth or Views & Illustrations of Trades Manufactures Produce & Commerce, 1826). “Tobacconists should occasionally give away cards in the shape of [clay] pipes; new styles can always be invented” (William Smith, “Advertise. How? When? Where?”, 1863). “Pipes are made in a great variety of shapes, and lengths, from four to twenty-seven inches, designated by a curiously recondite vocabulary, the origin of which is too profound a subject for light investigation” (“Broseley,” American Artisan, February 21, 1872). “The better criterion of age is the form, and the examples in existence shew the most prevalent shapes at different periods. The barrel-shaped bowl was most during the Commonwealth and the reign of Charles II, although it was made in many various shapes. …In the reign of William III., a more elongated form of bowl began to be prevalent, probably introduced from Holland, although the barrel-shaped bowl still continued to be used. In the middle of the 18th c., the wide-mouthed bowl, now to universal, became the prevalent form…” (Chambers’s New Handy American Encyclopædia,1885). “The names and shapes of Clays are legion, and the illustrated catalogue of the clay-pipe maker is a study in itself” (“Concerning Pipes,” All The Year Round, September 9, 1893). “These old [clay] pipes have been given names by rustics and uneducated people—they are known as Celtic pipes, Dunes’ pipes, Elfin pipes, Cromwell pipes, Fairy pipes, and even Roman pipes” (T. P. Cooper, “The Story of the Tobacco Pipe,” The Reliquary and Illustrated Archæologist, 1907). Quite often, the clay pipe was named after the place where it was manufactured, e.g., Broseley, a concept that made perfect sense. “These were the basic, most common forms of pipe, but because there were small clay-pipe manufacturers all over the country, there were a great number of names and shapes” (Matthew Hilton, Smoking in British Popular Culture 1800–2000, 2000).

Native-American Pipes

Joseph D. McGuire remarked: “There is undoubted evidence that pipes throughout the continent were made in many shapes, though it is probable that the most elaborate are the most modern. …All wooden pipe stems are not round; some are flattened, parallelograms, others are triangular, ellipsoidal, or even square…” (Pipes and Smoking Customs of the American Aborigines, 1899). “Shaped Pipes are so called from their shape. The Circular Peace Pipe, with its multiplicity of stem–holes, is always circular in form as the name ... The Keel–shaped Pipe is made in the shape of the prow of a boat with a projecting keel, from which it derives its name. …Vase-shaped pipes are so called from their shape” (George Arbor West, Tobacco, Pipes and Smoking Customs of the American Indians, 1934).

Meerschaum Pipes

The 200 or so years of meerschaum pipe and cheroot holder production were essentially a period of transition. In the early years of Hungarian production, three bowl shapes prevailed: Debrecen, Kalmasch, and Ragoczy. From about 1850 to about 1925, the meerschaum pipe industry is best described as unstructured, unrestricted, and individualistic. Carvers throughout Europe and the United States abandoned those three shapes and demonstrated imagination and ingenuity in their two- and three-dimensional creations that defied classification. “Different men require varied types or forms of pipes; though the so-called ‘Bull Dog’ shape and the blunter ‘Hungarian’ pipe, and again, the egg-shaped bowl predominate” (Felix J. Koch, “Your Meerschaum Pipe,” Popular Science Monthly, September 1916). This adds little to the conversation.

The Ulmer

The very unique wood pipe bowl, the Ulmer, originated in Ulm, Germany, a town noted for its manufacture of assorted wooden pipe bowls. The prototype Ulmer bowl is attributed to wood-turner, Johann Jakob Glöckler, in 1733. Some have believed that its shape represented an inverted balaclava helmet. Its popularity quickly spread beyond the borders of that town. In time, Ulmers were also produced in both meerschaum and amber. This is easy: it’s a unique shape and it’s always been called an Ulmer.

Porcelain Pipes

In brief, from the mid-1700s through the early 1920s, the porcelain pipe was a product of Western European countries—Germany, France, Austria, Denmark, and the Netherlands—and, like meerschaum pipes, factories produced whatever bowl shapes were popular. The focus was not on bowl shape; it was on the bowl’s art work, whatever the hand-painters employed at the factory were capable of creating. “…and The Thuringian forests of Middle Germany for their porcelain pipes, which are pressed onto every possible shape, and ornamented with every known color” (“The History and Mystery of Tobacco,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, No. LXL, Vol. XI, June 1855).

Briar Pipes

In the early stage of manufacture, “Briar-root blocks are cut into about 25 different sizes, and three principal shapes. The shapes are ‘Marsellaise,’ ‘Relevé,’ and ‘Belgian.’ The first two are the more usual shapes” (“The Briar-Root Industry in Italy,” English Mechanic and World of Science, September 21, 1900). It’s only after manufacturers turned blocks into finished pipes, did these manufacturers choose various names for the shapes they produced. Beginning in the late 1800s, there were more than a handful of briar pipe makers in England, but no written record exists as to how or why they gave names to their shapes, some of which continue to be produced to the present day. Most of these attempts do not mention the origin of briar pipe shapes and names. Was it terra incognita for all those 20th century correspondents and reporters?

I’ll start with this quote from the previous century: “Fancy titles, such as ‘Chubby,’ ‘Tourist,’ ‘Regent,’ and ‘Midget,’ are given to the many shapes in briars, and the nomenclature greatly assists the smoker in re-ordering” (“The Recent Window Dressing Competition. Mr. Ransford” (Tobacco, June 1, 1896). The Strand Magazine (June 1906): “Dunhill’s Patent Shield Pipe…First Quality Briar with finest vulcanite hand-finished mouthpiece. All shapes.” “The Rhodesian pipe, the Pan shape and the Calabash shape, are all models of more or less recent invention, and calculated to catch on well with the trade” (“English Pipe Novelties,” The Tobacco Leaf, April 29, 1908).

Was this the origin of the Bulldog? “Looking neither to the right nor left and exclusive to the point of snobbery, a bulldog, holding a briar pipe in his teeth, cut a wide swath on Superior Street yesterday. …Nipper [the dog’s name] has adopted the practice of taking a constitutional with a pipe in his mouth, because he is a bit blasé and needs a new sensation. Occasionally he allows his pipe to be filled and lighted, and emits tiny puffs of smoke. He is forbidden to inhale” (Dogdom, March 1913). Close enough, but no cigar. “In commercial importance the briar pipe is easily first, and an almost infinite variety of shapes, sizes and styles find favor with the increasing number of pipe smokers in our city communities” (“Tobacco Products in the Drug Store—III,” American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record, November 1913).

“As to the best shape for a briar pipe, this is a matter of fancy. In the catalogue of one well-known firm there are no fewer than one hundred and fifty different shapes” (“Smoke,” Pearson’s Magazine, Vol. XXXVI, July to December, 1913).

“For a long time it was thought that imported briar-wood alone could be used to make a good pipe, but recently an American factory undertook to experiment with walnut and successfully too, for after having made a simple little article in the shape of a congo pipe at an inexpensive price walnut wood is now being used to turn out pipes of every size and shape to retail at a quarter each” (“Hardwood News Notes,” Hardwood Record, April 10, 1917).

One [concern], for instance, was the matter of indiscriminate style inflation. Without any apparent reason other than trade fancies, it had been the custom in the trade from season to season to offer novelties in a given line of pipes. These styles were rarely more than slight variations on existing shapes, and were simply sops for a trade demanding ‘something new,’ despite the fact that the average pipe smoker runs to definite standard shapes. …A few years ago the company [William Demuth] began to try to cut down the number of styles in a given line to twenty-four. It featured certain of these models in the Hand Made, one by one, and mentioned the fact that the line carried twenty-four of these standard shapes in various grades and at various prices” (“Digging in” for Peace,” Printers’ Ink, October 31, 1918).

“If you would be a good salesman it is necessary to know as much as possible about the article you are selling. This is particularly true of pipes. The deeper you go into the history of pipes the more interested you become. Below are shown some of the principal shapes with their correct names: Bull Dog (straight), Bull Dog (bent), Egg (straight), Egg (bent), Unger (straight), Unger (bent)” (“Pipe Points Worth Knowing,” The United Shield, August 1919). The “Standard Pipe Styles” in Carl Werner’s Tobaccoland (1922) were Straight Bull Dog Shape, Bent Bull Dog Shape, Straight Egg Shape, and Bent Egg Shape. To Werner, styles and shapes are interchangeable.

“They [Bewlay pipes] are made in every model and for every purpose and may be had in the ordinary style or fitted with the Bewlay Pipe-lip, Bewlay Patent, or both. The stock includes pipes of every description, pipes with straight or curved stems, long pipes, short pipes, patent pipes for motorists, yachtsmen and others who smoke in the open; pipes with large bowls, small bowls, flat-bottomed bowls for standing on tables, cutties, bull dogs—in short, pipes for every purpose (“Bewlay & Co., Ltd.,” Tobacco, July 27, 1922). “Since the establishment in 1899, Duncan’s has built up an enviable reputation for manufacturing briar pipes. …The Zoie de Luxe briar is made in more than a hundred shapes” (“Duncan’s,” Tobacco, July 27, 1922).

The M M Importing Company, the U.S. agent for Dunhill, was a New York retailer and wholesaler of “…smoking mixtures, smokers’ requisites and superior pipes. …Pipes are displayed in wall cases in which are small drawers, each containing ten pipes of the same shape. Each pipe bears a number distinguishing its shape. The customer selects the desired model, the drawer containing the pipes bearing the corresponding number is withdrawn from the case and placed on a shelf before him, and he then selects the pipe which appeals most to him by its grain and color” (“The M M Importing Co.” Tobacco, July 27, 1922). Numbers, not names!

Another distinctly modern development in pipe manufacturing is the standardization of styles and shapes. For half a century the number of styles or shapes a manufacturer produced was limited only by his imagination and ingenuity, or rather his lack of these two qualities. He would make any old kind of pipe that anybody asked for. Modern production methods prohibit this. There have always been certain shapes and styles that were in greater demand than others. Efficiency required that a proper analysis be made of the salient features of the best selling styles, and that these be standardized into a small yet universal line. Among the standard shapes evolved, the best and most commonly known are: The Bull Dog Straight; the Bull Dog Bent; the Egg Straight; the Egg Bent; the Dublin Straight; The Ungar Bent; the Poker Straight; the Woodstock Half-Bent. By varying the proportions and sizes, these shapes can be made into a wider selection of styles (George R. Wilson, “The Milestones of Pipe Progress Through Various Stages,” Tobacco, July 27, 1922).

In the 1920s, Kapp & Peterson ads read: “Below are a Few Shapes Popular in the U.S.A. There are 500 Other Patterns to Select From,” and “The Kapet in 36 bent and straight shapes, retails at just under $2 and is a good value for money.” “Harwood Brothers make these pipes in all shapes and sizes and it would seem there should be a niche in the pipe smoking world for this sort of product…. It is put out in more than 100 patterns, and if a pipe without silver mounting is required the retail price is only 50 cents. The makers are the Civic Co., Ltd., Hammersmith, W. 6” (“Empire Grown Tobacco Fostered by British Gov’t,” United States Tobacco Journal, January 12, 1924).

“There are more than 60 [Weingott pipe] shapes to choose from, …Ben Wades of Leeds, maker of the Larnix cigarette tube, is now marketing the Ben Wade pipe in 60 shapes” (Jack Brooks, “British Dealers Enjoy Big Cigar Trade Last Month,” United States Tobacco Journal, January 19, 1924). “More than 100 shapes in City De Luxe and G.B.D. are being marketed at $1.36 and $1.62 each…”and “The great range of pipes manufactured by Oppenheimer’s, Finsbury Square, E. C., enables the smoker to choose the model that is exactly suited to his temperament.”

(“American Dealers Could Learn Much From The English,” United States Tobacco Journal, February 23, 1924). (Do you really believe that these companies had 60, 100, 500 shapes in their product line, or was this just marketing hyperbole?)

“Milano [WDC] comes in 37 smart shapes, smooth finish, $3.50 up. Rustic models, $4.00 up” (Life, March 4, 1926). New York’s Manhattan Briar Pipe Company’s ads read: “Made in all shapes–Briar, Calabash and Meerschaum.” These are not shapes. “There are more than 100 Parker shapes the two most popular models being the super bruyere and the briar bark” (“Tobacco Industry to Play Big Part in British Exhibition,” United States Tobacco Journal, January 19, 1924). Bruyere and briar bark are not shapes. “Marxman makes superb pipes in all shapes, standard and exclusive…in all price ranges.” Sears, Roebuck and Co. ads about its assortment of briars as “shapes of several patterns.” Kaywoodie ads in Montgomery Ward catalogs of the early 1940s: “Choose the shape that suits you. Specify by letter: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H.” Ads full of ambiguity. One might say that several of these ads, however unintentional, are misleading.

“Allow the customer to hold the pipe in his hand, and don’t show him too many shapes at one time or you will confuse him. …Odd shapes are now in great demand. This is due to the fact that a real pipe lover wants several pipes, and each pipe must be a different shape” (“Do You Sell Pipes or Just Keep Them?”, Tobacco, July 31, 1924).

There is another pipe, apparently of a new design, which seems to have great potentialities as to popularity. It gives the idea that the maker was engaged in whittling out a bulldog pipe, such as was familiar along about 1898, when somebody stepped on it. Another impression is that the pipe when it started out was a bulldog pipe all right, but became softened by internal heat and settled. This pipe is a favorite, apparently, with the home town collegiate class. After observing pipes for a while, the non-pipe smoker finds himself impelled to ask: ‘Why so many styles of pipes? If there is one form of pipe which lends itself better to burning tobacco than another, why do not manufacturers and the smokers concentrate on that?’ (“Pipes Are Regaining Their Own as Adornment of Masculine Countenances,” Tobacco, July 30, 1925). At one time it was said, quite truthfully, that a pipe was a pipe, an’ all a’ that. Perhaps this was so. It is possible that a standard sized and straight shaped pipe, of the briar variety, was, at one time, sufficient for the American smoker. But not today—not much! Fact of the matter is, it surely must have been years and years ago that a very few standard pipe shapes were sufficient to appease the average smoker’s idea of the proper pipe. At any rate, the stock styles and stock numbers of the several large English and American plants do not bear out the assertion that pipe smokers are not a finicky, fussy, particular class of individuals. Because, in the last few generations, actually several hundred thousand pipe styles have been devised and manufactured by the various plants in this country alone! Styles and shapes of briars are more numerous today, undoubtedly, than ever before, notwithstanding the leading manufacturers’ efforts to reduce their stock members to a reasonably few designs. …Plain, smokaday briars have rapidly changed also. For instance, the old, original mahoganized briars, of numerous shapes, have been replaced by a standardized few in the more classical styles, now preferred by the younger generation. These styles consist of shell briars (also revived), with their carved contemporaries. …Styles of pipes will continue to be the current fads of smokers, as they have almost assuredly been in the many generations which have preceded us (“Stylish Pipe Smoking,” Tobacco, August 19, 1926).

Writing about retailers, R. C. Pulver asserted: “These progressive tobacconists watch the pipe market, especially the English or London ‘style’ market. For it is from London, really, that most pipe ‘styles’ originate. English smokers, like some Continentals, are keen on pipes. Give them credit, they ‘know’ pipes. They know the woods, they know the mounts. They know what shapes to offer and to sell each individual smoker” (“National Advertising Needed to Promote Pipe Sales,” The Fourth Estate, November 26, 1927).

With respect to the significance of the fact that parts of the imports of brierwood pipes consist of smaller than ‘standard sized’ pipes and of specialty and novelty pipes it should first be noted that the domestic production of brierwood pipes also includes non-standard types. Before 1950 several domestic producers turned out, at least occasionally, some fancy carved pipes somewhat similar to the imported specialty or novelty pipes. Recently, however, there has been only a very small domestic production of such pipes and only one domestic concern now regularly produces them. Small-sized pipes have been produced in recent years by at least seven domestic concerns that are still in operation and such pipes accounted for about a twelfth of the domestic production of brierwood pipes in 1952 (United States Tariff Commission, Tobacco Pipes of Wood. Report to the President on the Investigation Under Section 7 of the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951, December 1952).

Something from The Geographical Magazine (Volume 38, 1965) might have shed some light, but this is all I could capture from the Web: “Yet it was not until 1879 that a Frenchman came to England to make the first briar pipe. ... some seventy different shapes: shapes with interesting names such as ‘Zulu,’ ‘Medium Apple,’ ‘Saddle Billiard’ and ‘Ringed Bullcap.’” Weber’s Guide to Pipes and Pipe Smoking (1970): “Traditionally, special names have been given to various pipe styles that combine certain shapes of bowl and shank.” Huh?

Names assigned to various shapes may or may not have relevance to the form of their shape. Names like Apple, Pear, and Pot describe outer shape resemblance to those objects, but there is nothing that resembles a Prince. …A few decades ago the selection of shapes was much smaller than today and most of those shapes were produced in all countries in essentially similar forms. They became the ‘Classic’ or ‘Standard’ shapes. They are still produced, but enormous competition among pipe manufacturers forced a continuous search for new shapes. The easiest way for a manufacturer to develop a new shape was to make small, insignificant changes on classic shapes, compatible with his machinery (Pimo’s Guide to Pipe-Crafting at Home, 1976).

“In all, some 1600 different pipe styles come out of Saint-Claude...” (John A. Linkletter, “The Art of Making Briar Pipes,” Popular Mechanics, February 1977). “Pipe designs that have become classics over the years combine smoking comfort with a pleasing shape and balance” (Garth Graves, “Carve your own dream pipe,” Popular Mechanics, May 1977). “A number of other names given have meanings which can be guessed at, and a few names, such as a ‘Dublin,’ refer to bowl shapes which still exist in today’s brier pipe industry” (Iain C. Walker, Clay Tobacco Pipes, 1977). The Encyclopedia of Collectibles (Volume 12, 1978): “…each standardized [briar pipe] shape has its own name, in many cases purely fanciful.”

“Pipe shape names seem to differ by manufacturer. …You will see many more exciting shapes in the world of pipes, hand-made by individual craftsmen, while some will be stock shapes in use by specific companies. Each company has unique names given to their sleight [sic] variations on shape. …The calabash can be almost any shape, receiving it’s [sic] name for the combination of gourd and meerschaum rather than the actual shape” (Royce Davis, The Gentleman’s Guide to Pipe Smoking, 2013). And this, “Commercially designed tobacco pipes take refined shapes with curved contours, while those hewn by artisans often employ eccentric form” (Celia Rabinovitch, Duchamp’s Pipe, 2020).

Did any of these quotations resonate with you? Would you agree that not much in the way of specifying who, how, when, or where all the shape names we are familiar with were generated? Whether consciously or unconsciously, ads used words such as finish, size, and price, with an absence of words such as pipe shape and pipe-shape names. But I realize that in the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms.

Mission Unaccomplished

Jacques P. Cole, the son of J. W. Cole (The GBD St. Claude Story), a founding member of the International Academy of the Pipe, was steeped in the pipe trade. After WWII, he joined his father at GBD in Saint-Claude, then to Comoy as a factory manager, then to Charatan, and back to Comoy as a sales manager. Jacques was a prolific writer. As a member of the International Academy of the Pipe, he authored two articles in its annual publication, The Pipe Year Book: "Briar pipe shapes, 1939 to 1996” (1997), and "What’s in a name? A look at pipe brands" (1998). His four-page pamphlet, Briar Pipe Shapes & Styles. Pipe Line Guide No. 1 (1985/1990) shed some light on this topic. He also wrote a brief article, “Guide to Pipe Shapes & Styles” (PipeSmoke, Fall, 1998) that can be read in full at pipesmagazine.com. A detailed explanation of the origin of pipe shape names or nomenclature might have become public knowledge if his manuscript, A World of Pipes. A History and Study of Briar Pipemaking, had been published. In 1985, he had sent me a copy of the draft for review, so I am very familiar with its contents. He was invested in tracing the origin, cataloging, and classifying some of the standard pipe shapes … serious research into a little-understood facet of tobacco-pipe terminology that did not see printer’s ink. After he passed away in 2014, his personal papers were donated to the National Pipe Archive (NPA). In October 2023, when I asked David Higgins, an NPA co-founder, if those papers were now accessible, he replied: “It is one of several large ‘to do’ jobs on our pending list.” When available, Cole’s research will, no doubt, be a valuable resource for the study of the briar pipe industry in Great Britain and France. (The NPA holdings—although its major research focus is clay pipes—include records and trade catalogues from briar-pipe manufacturers and retailers, such as BBB, Charatan, Civic, Comoy, GBD, Lecroix, Oppenheimer, Orlik, Peterson, and Tranter.)

Where else might one look for information? There are a few YouTube videos, e.g., “Tobacconist Field Guide: Pipe Shapes,” “Pipe Shapes & Tobacco Types,” and “Different Types of Tobacco Pipes.” But don’t look to The Tobacconist Handbook. An Essential Guide to Cigars & Pipes for information about pipe shapes. As one reviewer noted: “I recommend this for cigar enthusiasts but pipe lovers should look elsewhere.”

I turn to the decentralized Web as the second source for information, knowing that not all Web sites are created equal, that they differ in quality, purpose, and bias, and that anyone can post anything. (I am not a loyal friend of the Web!) I hoped that, by interrogating the Internet, I might find the Holy Grail, or the Delphic Oracle, or the Wise Man of pipe terminology or, maybe, a Darwin’s On the Origin of the [Pipe Shape] Species. For the last 40 years, it has facilitated the greatest expansion in information access in human history, the spread of knowledge, and a tool for education, but it is often a less-than-reliable source. On it are many glossaries for the pipe smoker to enrich his knowledge:

- A Complete Guide to Tobacco Pipe Shapes (tobaccopipes.com)

- A Guide to Different Pipe Shapes and Materials (cigarsltd.co.uk)

- A Guide to System Shapes, 1896–2019: Part 1 (The 300 Shape Group) (petersonpipenotes.org)

- A Guide to Peterson System Shapes, 1896–2019: Part 2 (House Pipes, Straights & Peculiars)(petersonpipenotes.org).

- Briar Pipe Guide: Finishes, Mouthpieces and Tips for Use (paykocpipes.com)

- Different Tobacco Smoking Pipes: Shapes, Styles, Designs & Materials (bespokeunit.com)

- Glossary (smokingpipes.com)

- Glossary of Tobacco Pipe Terms (pipeclubofindia.com)

- Glossary (tobacconistuniversity.org)

- Glossary (pipedia.org)

- Glossary of Tobacco Terms (aointl.com)

- Guide to Tobacco Pipe Shapes (thepipeboutique.com)

- Pipe Glossary (pipearchive.co.uk)

- Pipe Shapes (pipeshop-saintclaude.com)

- Pipe Shapes (gqtobaccos.com)

- Pipes and Shapes (pinterest.com)

- Pipe Shapes. A Look at Old and New (glpease.com)

- Pipe Shapes & Various Tobaccos (badgerandblade.com)

- PipeSMOKE’s Guide to Pipe Shapes and Styles (pipesmagazine.com)

- Pipe Smokers Glossary (thepipeshop.co.uk)

- Pipe Smoking Terminology (the-tobacconist.co.uk)

- Pipe Tobacco—A Complete Guide (enjoydokha.com)

- Smoking Pipes Glossary (smokingpipes.eu)

- Smoking Pipe Shapes (fumerchic.com)

- Smoking Pipe Shapes Guide (thepipeguys.com)

- The Complete Guide to Tobacco Pipes (havanahouse.co.uk)

- The Many Shapes and Styles of Tobacco Pipes (smokingpipes.com)

- Tobacco Smoking Pipes (cigarcigarinfo.com)

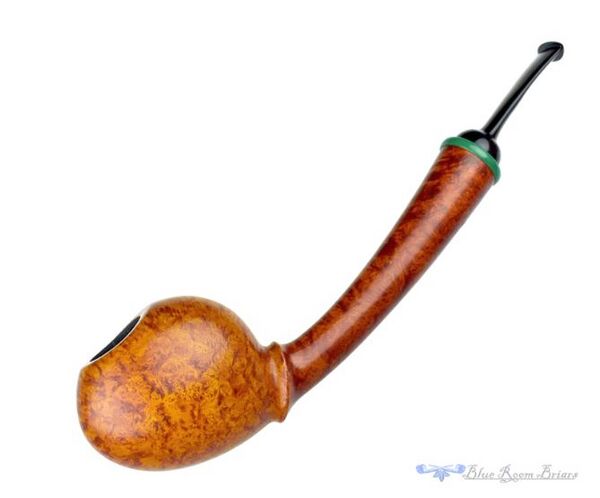

This table lists traditional pipe formats and a few new ones. As you might expect, there is some variance in the content and character of each glossary. I reviewed each to identify those pipe shapes and names that most should agree on. I have not included any variants, such as bent, half-bent, full-bent, paneled, and squat, or the many different mounts and mouthpieces.

| acorn/pear | cutty | opera/oval |

| apple | diplomat | panel |

| author | Dublin | pickaxe |

| ball | duke/don | poker/poser |

| ballerina | egg | pot |

| Belge/devil anse | elephant’s foot | prince |

| Billiard/néogène | Eskimo | Ramses |

| blowfish | fleur/flower | Rhodesian |

| bulldog/Haiti | hawkbill | sitter |

| bullmoose | horn/oliphant | skate/skater |

| brandy | Liverpool | snail |

| calabash | lovat | strawberry |

| Canadian | lumberman | tankard |

| cavalier | mushroom | tomato/ball |

| chimney | nautilus | ukulele |

| churchwarden | nose warmer | volcano |

| cobra | Oom Paul/Hungarian | Zulu/yachtsman/woodstock |

On pipedia’s Glossary page: “This Glossary needs to be updated as more terms and acronyms are added to our pipes and tobacco lexicon daily.” On tobaccopipes.com’s Glossary: “We consider this an almost complete guide because the shapes and forms of our favorite tobacco pipes are constantly evolving.” Both statements are accurate. There are also many pipe-shape charts on the Web, but there’s no consistency, uniformity, or agreement among all of them. Here’s what I scraped off the Web. Unlike the previous section, these quotations are not in any particular order of significance. You will read several attempts to explain how certain pipe shapes came into existence and how they got their names. I start with Web question 1: “Why are pipes different shapes?” The answer: “Wider chambers can allow for a bit more flavor, but they will tend to be marginally hotter. Narrow chambers may slightly reduce the taste, but will smoke a bit cooler.” Another online explanation to this question is “The shape will most likely impact how comfortable the pipe is while in your mouth.” Web question 2: “Why do pipes have round shapes?” The answer: “You have probably noticed that most fluids, especially liquids, are transported in circular pipes. This is because pipes with a circular cross section can withstand large pressure differences between the inside and the outside without undergoing significant distortion.” Not what a pipe smoker would expect as answers to these two questions. If your favorite pipe is a Diplomat, wouldn’t you desire to know its provenance, why it’s called a Diplomat? Surely, inquiring minds would want to know.

What follows is an assortment of quotations ranging from the confident and the tentative, to the indecisive and the skeptical, which is understandable, considering that this topic is essentially uncharted. And being unchartered, you can’t fact-check what you will read, but everyone seems to agree on the essentials.

Pipes come in vast array of shapes and sizes. From Classic English Shapes, to the more Free Formed Danish Shapes. It can be a minefield when starting out, so many shape names, which are often subjective and often cause augments [sic] with makers and smokers alike. …Many pipe makers and smokers disagree on the names of some pipes, these usually involve the Bulldog & Rhodesian shapes. For the purpose of this article i [sic] will use the same names that Dunhill and many UK makers use. …This is not a complete list, over 100 shapes and styles are produced world wide. Each country has its own styles and shapes. Many factories release limited edition pipe [sic], often in unique and unusual shape [sic] (gqtobaccos.com).

With the mention of Danish freehand briar shapes, I suggest that you read a full account by Jakob Groth, “Pipe History,” scandpipes.com.

Rick Hacker: “Just as cigar shapes have names, such as Churchill, Panetela and Lonsdale, so, too, do pipe shapes have nomenclatures to help in their identification. Billiard, Canadian, Apple, and Bulldog are just a few. The list is so extensive that it would take the rest of this magazine just to list and depict every shape” (“For Pipe Lovers,” cigaraficionado.com, Autumn, 1993). “Briar pipes are available in a wide variety of standard shapes, well over a hundred in fact” (tinderboxinternational.com).

There were 69 Kaywoodie shapes including their variants in 1947. “Kaywoodie pipes were available in 18 different finishes with about twelve different shapes per finish” (greywoodie.com). The company promoted its own shapes using modifying adjectives: the Ninety-Fiver Apple, Connoisseur Bulldog, Carburetor Apple, Centennial Pot, and Silhouette Billiard, but I could not differentiate their versions from others that produced Bulldog, Apple, Pot, and Billiard pipes. “A [GBD] shape chart of 1886 shows a basic 125 shapes (the actual total was 1600 which included 12 Billiards, 36 Bents and 46 Dublins/Belges) many with heels” (“Finding Out Who Created GBD—Story of a Pipe Brand—Jacques Cole,” rebornpipes.com).

Often, Wally Frank ads in magazines would read: “FREE. Big, colorful 52 page illustrated Pipe Catalog for lovers of fine pipes. Every known pipe shape in briar, meerschaum and calabash.” Early on, Charatan kept things simple: no shape names … just straight grain, special, and relief grain. So did Butz-Choquin and Barling in several of its retail catalogs. “Also, at some stage before 1968, shape names were replaced by shape numbers, apparently all incorporating three digits and beginning with a 9. For example, a 910 was a billiard” (Loèwe & Co., pipedia.org).

“When briar was first used in pipemaking, the shapes and models hardly differed from those made from other materials. But by the time the briar pipe industry was fully established in 1855–1860, pipe makers had realized the flexibility of the material, and briar pipes began to acquire their own characteristics. As a result, the demand for briar pipes grew very quickly and a basic range of popular shapes and models was developed. These shapes still form the foundation for current models on the market” (pipesmagazine.com).

“Tobacco pipes come in countless shapes and sizes, which can be simply overwhelming if you’re looking to buy one. Furthermore, they can also be made from a variety of material, each with their [sic] own aesthetics and characteristics. …There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of different pipe shapes and designs. Broken down into nine families” (bespokeunit.com). “More shapes and variations exist than can possibly be listed but there are some common, classic designs to be on the look for when check out pipe shapes. Two broad categories include straight and curved pipes with variations within these two categories. …Tobacco pipes come in a wide array of shapes, each with its own history, aesthetic appeal, and influence on the smoking experience” (thepipeboutique.com). “There is a large range of pipe shapes available on the market worldwide, and there can sometimes be a little discrepancy between pipe makers and smokers as to the shape names” (cigarsltd.co.uk).

“There are more shapes and variations on shapes that one could possibly list and talented artisans create more every day. …Over the centuries many styles of pipe shape have appeared and faded. In today’s pipe world they are generally thought of in terms of classic English shapes and Danish, or sometimes freehand shapes. …Generally, pipes fall into two broad categories that are defined by the course of the smoke channel. These are simply straight and curved. From there, one can jump off into an ever expanding realm of marvelous and creative shapes” (Steve Morrisette, “Guide to Tobacco Pipes & Pipe Smoking,” gentlemansgazette.com).

“Briar pipes are available in a wide variety of standard shapes, well over a hundred in fact” (tinderboxinternational.com). “Pipe smoking used to be an occasional part of life back in the days. Though recently, the youth have also adapted pipe smoking, which brought about the invention of many different shapes of pipes” (allin1smokeshop.com). “There is a wide variety of different shapes of pipes on the market around the world, and there may sometimes be some disagreement amongst the builders and smokers about naming a particular shape” (“What is The Best Pipe Shape For Smoking,” medium.com). “There are sixteen models and ten finishes in the Brebbia line. …There are 106 different shapes in the line” (monjureinternational.com). This is very carefully construed and guarded comment: “Pipe making is not an exact science. It is an art, and art produces only variations on a type” (cupojoes.com).

“Of course naming a pipe shape is as old as pipes and pipe-makers. In the early days of briar pipe-making companies commonly had different names for the same shape, but over time one name usually took the ascendancy and a shape settled down to just one name—Dublin, bulldog, and Rhodesian come to mind. Or in some cases, the pipe is known by two names—the Oom Paul (or Hungarian) and the Zulu (often called a yachtsman by the Great Generation)” (petersonpipenotes.org).

“Somehow, quite early in the history of briar pipes, the shape name came to be associated with the town bearing its name. It doesn’t really matter, I [Mark Irwin] suppose, whether it was a name used in an early pipe catalog or a name like the ‘dutch’ billiard coined by servicemen (petersonpipenotes.wordpress.com). “Even more recent artisan shapes, once they become common enough, generate a common name—blowfish, volcano, acorn and fig, to name a few” (“44. The Peterson ‘Bent Dutch’ Shape Name,” petersonpipenotes.org). And fearsclave (pipesmagazine.com) agrees: “And some shapes are recent enough that we know their origins.”

This is from tobaccopipes.com. “Why Create this Guide? We are sure that many of you are wondering why in the world we decided to create this resource. The reason is simple: this is a field of pipe knowledge that is muddy and extremely full of varying opinions. If you go to two different local tobacconists and ask each to define a pipe shape, i.e., a Blowfish, you are likely to receive two different definitions of what constitutes the shape. The same is likely to happen online, you may find two completely different descriptions as to what a Blowfish pipe is. … You have most likely noticed a plethora of pipe shapes, styles, materials, and finishes by now. We understand how it may be a bit overwhelming.”

“Somehow, quite early in the history of briar pipes, the shape name came to be associated with the town bearing its name. It doesn’t really matter I suppose whether it was a name used in an early pipe catalog or a name like the ‘dutch’ billiard coined by servicemen returning from the Boer Wars. But if any pipe maker might be said to have proprietary rights to the shape, I’d say it would have to be an Irish one, wouldn’t you?” (“172. A Catalog of Peterson’s Dublin Shapes, 1896–2020,” petersonpipenotes.org). “The majority of pipes today are based on half a dozen basic shapes. These shapes can incorporate straight or bent styles and can be squished, stretched, or manipulated to create new or different shapes” (davidus.com).

“Names like Apple or Brandy seem obvious from their shape, and we all know the origin of the shape name ‘Bing Crosby,’ but then there’s Dublin, Zulu, Billiard, Bulldog, Author, and others...and Poker…that are not so obvious. …Recently I showed a poker to a friend. The first thing he did was grasp it in his fist with the stem pointing away from him. He began making jabbing motions with it, saying he understood how it came to be called a ‘poker.’ That may be, but then there’s the game of poker, the poker fireplace tool, Poker is a surname of English origin, and there’s probably a place-name Poker somewhere as well. It got me wondering about other standard shape names” (brothersofbriar.com). A few days ago, I started wondering about the history of the present-day array of pipe shapes. There seems to be some literature our there; clays, for example have been the subject of a lot of archaeological study. And some shapes are recent enough that we know their origins. Princes and Oom Pauls are the classic example of these, although I have to wonder whether the Oom Paul had been around longer, and just got nicknamed after Paul Kruger. But the thing is, somewhere between the briar’s arrival on the scene and the plethora of shape [sic] we have today, a whole bunch of shapes were developed, and it’d be really neat to know, say, when the Bulldog first appeared (and whether it or the Rhodesian came first). It’d also be kinda neat to know what was trendy when; what all the swellest young Victorians were smoking in 1859, that sort of thing. I’ve been Googling away at this, but either my Google Fu is weak, or this sort of information seems to have been lost in the mists of time. Which strikes me as too bad. (fearsclave, “History of Pipe Shapes?”, pipesmagazine.com).

And Mso489 offered his views:

The pot is probably named after the standard cooking pot with a cylindrical shape. The brandy is clearly named after the shape of glass used to drink brandy which is tapered at the top to capture the fumes and enhance the sipping experience. The pot is probably named after the standard cooking pot with a cylindrical shape. The egg and acorn are shaped like those objects. The Dublin probably honors where these pipes were first made and/or were widely popular. The yacht/zulu ... I’d like to know ... maybe denotes the dashing shape, but like the author shape is probably a bit of good marketing. The bulldog? The diplomat? It seems creative carving always superseded discussion and recording of the invention of shapes. Ideas were passed along quickly in a see-do culture, with no one keeping journals or diaries of the process. How did the author shape edge into the diplomat, or vice versa, or the bulldog into the Rhodesian. Or the Calabash into the Dublin, and so on, and on. From the 19th Century (1800’s) on, pipe manufacture was highly competitive, so workshops were secretive about changes and innovation, and the visual appearance of pipes was one of the major ways to gain a competitive edge. Somewhere maybe there are diaries of one or two pipe carvers who also verbalized the experience and history of this, but little seems to have surfaced, as near as I can tell. Maybe a craftsmens’ [sic] ethic disdained and mistrusted talk and writing (“How Did Pipe Shapes Get Their Names,” pipesmagazine.org).

As to the aforementioned Rhodesian, here’s another explanation: “The Rhodesian shape, originating from England in the mid-20th century, showcases a distinct bowl shape with flattened sides and a rounded top. It draws its name from the diamond mines in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) that were prominent during that time” (thepipeboutique.com). This stretches the bounds of credibility.

Bill Burney has a good sensing about the mystery surrounding the billiard:

Some years back, I decided to do some research into the names of different pipe shapes, just to get a better understanding. This eventually led to my doing the ASP Pipe Shapes Chart. I don’t consider myself an authority on the subject, but I have studied a bit. For the new ASP website, I thought I might discuss some of the shapes in more detail. Arbitrarily, I decided to start with my favorite shape—the Billiard. …So, where did the name ‘Billiard’ come from? I haven’t been able to find a definitive answer. The best explanation I have heard so far was that at the time the shape was named, the game was very popular, so whoever came up with the name for the pipe shape named it after the popular game of the day. Maybe. Good thing the popular game wasn’t craps (“The Billiard,” pipedia.org).

This is yet another opinion about the billiard. “…basically the French “billard”/“billart” means a bent stick or piece of wood, or a cudgel-shaped piece of wood. In other words, if billiard (the pipe) is French in origin, it’s probably based on the shape of the basic briar pipe—i.e., straight, but with a shorter piece sticking out (i.e., the bowl)” (pitchfork, pipesmagazine.com). In French, a bent stick is un bâton plié, a piece of wood is un morceau de bois, and a cudgel is une trique. I have no rejoinder!

This is a detailed explanation of the Churchwarden:

[T]here are three main theories, given here in reverse order of likelihood: the first, that smoking was permitted almost everywhere, including churches, in those dear lost days, and the long length and design of the pipe allowed it to rest on the pews; the second, that certain individuals, erroneously called churchwardens and trusted with guarding England’s churches in the 1800s, very much enjoyed their pipes and fancied the popular style, and the third, that real churchwardens (who by every official definition were not guards but honorary officers of local parishes or district churches entrusted with administrative and other minor duties) became known for their love of the pipe later named for them (rebornpipes.com).

Simong (pipesmagazine.com) added: “Churchwarden—the pipes were that length so they could stand by a window, with their bowls outside so as not to molest the congregation with their smoke.”

In my judgment, the most relevant contribution is from Chuck Stanion (smokingpipes.com): “The Many Shapes and Styles of Tobacco Pipes.” I quote portions:

You may have noticed that pipes appear in a large number of different shapes. One might even say that the number is infinite, especially when accounting for variations. Most traditional shapes, for example, can be straight or bent, with varying proportions, different stem configurations, different capacities, different balance, rounded or flat rims, varying curvature of bowl, length of stem—there’s no end to the differences possible with pipes. For those who have no interest, they probably all appear the same. We tend to remember things emblematically, so those who are apathetic regarding pipes probably register any they see as ‘a pipe’ with whatever low-resolution image their particular brain uses to bookmark such concepts, just as some people might not see a difference in fishing poles, pens, or golf clubs. But those of us interested in pipes pay more attention to them and recognize the differences.

With so many shapes, we need the vocabulary of names to distinguish between them, and we have a large vocabulary for that purpose—some might say an overabundance. But it’s helpful to know the differences, especially in the families of shapes that are most attractive to us personally.

It might be said that all shapes start with the Billiard and divert from there. The Billiard is the archetypal shape and the most traditional. From the Billiard spring other related shapes: the Lovat, Lumberman, Dublin, Brandy, Apple, Liverpool, Canadian, Chimney, Panel (aka Foursquare), and Pot, for example, and other variations extending from the original. Even Freehands might be said to be Billiards with complex carving instead of simple, rounded bowls… The names given to the various shapes are often pretty simple: Apples, for example, look like apples, Brandys look like brandy snifters, Horns look like horns. That makes them easier to remember, but it isn’t a perfect system. Liverpools don’t look like Liverpool or any other city, but many shapes are named more eponymously.

From Gabriel Bass, “In Praise of Traditional Pipe Shapes” (smokingpipes.com): “After determining what makes a Liverpool different from a Lovat (hint: it’s the stem), it becomes possible to read shape charts like style guides for the different marques, each with its own flavor and variations on the same handful of basic forms. …Looking at the history of pipe design, one can see the predecessors to many common shapes in pipes that pre-date the widespread adoption of standardized shape charts. The Cutty and Belge, for example, are directly borrowed from designs popular when clay and meerschaum were the most common materials for pipes. One can see how the now ubiquitous Billiard shape evolved from the clay pipes of yore as the shape was tweaked and perfected to perform best in briar form.” As well, Truett Smith, another smokingpipes.com contributor, wrote a series of articles on the history of pipe design in Denmark, England, France, and Italy. His mission was “…to map and untangle that metaphorical web of pipe design.”

All these observations add to our knowledge and understanding, but none have tackled the difficult topic: how was this name assigned to this shape? Lots of folks have a general idea or an opinion about the origin of some traditional pipe-shape names, but no one seems to have a complete understanding of them all. This is not a criticism. It’s an observation.

More Questions Than Answers

Did you ever wonder why a particular name was chosen to describe a pipe, to personify its shape with an alluring nom de plume? I find that some names are imprecise, some don’t make sense, some defy explanation, and others are superfluous. Many are flights of fancy, spur-of-the-moment, capricious … an unusual assignment of labels or designations to particular pipe shapes. Are you able to conceptualize or envision a certain pipe image by its assigned shape name? Admittedly, a few, such as apple and brandy, seem obvious—a few are hybrids—but the others? I am not a member of The Words Matter Movement, but words do matter, even for the humble pipe. Dunhill’s Duke or Don shape looks like a setter or a tankard, and is often confused with the Friendly, the Poker, and the Cherrywood. Its Collector pipe looks very much like an apple. I’m not a Dunhill expert, but the company is now rather careful in its promotion. On its website: “Pipes types include Root, Bruyere, Rubybark, Cumberland, Shell Briar among others.” And its system of describing pipes is by shape, finish, group, and stock number, e.g., “Dunhill Chestnut Prince, Group 3 Pipe, #101-6688,” which leaves little doubt as what this pipe is.

I don’t mean to denigrate Denmark’s Erik Nørding’s “freehand-wave” series, but I do take umbrage with his “Hunting 2011 The Brown Bear Rustic Fishtail pipe” and his “Hunting 2014 Crocodile pipe”; neither shape evokes a beast, but I am probably too literal. His latest, “The Compass,” is a cylindrical briar bowl with an aluminum stem, but I don’t expect it to indicate True North if I light it up. Of course, he can name his pipes anything he desires. Several makers in Europe craft fleur (flower) pipes, but none exhibit petals. I don’t know what is gained by the mystique of recent monikers. Maybe the first maker of a new-style briar pipe shape knighted it with an unusual or ambiguous name and everyone thereafter followed suit: craft a new, atypical pipe shape, author an appropriate name for it. Oops …author is a pipe shape.

“Ramses, Pickaxe, and Devil Anse—oh my. Some tobacco pipes simply defy easy description. Smoking pipe carvers create amazing shapes that never appeared in a catalogue” (thebriary.com). I’ll add a few more, such as flying saucer, Normandy, ocean, princeaple, prow, corn row, sandwich, sea shell, sportsman, tulip, and Vesuvius. Does the ukulele look like that musical instrument? Does the mushroom look like an edible fungus? Does the strawberry look like it belongs to the genus Fragaria? Isn’t the bull moose briar another name for the bent Rhodesian? Tom Eltang’s snail looks far different from Bill Walther’s snail and the one from Master Alexa. Why name a briar shape after the Eskimos? The Ramses, named after the Egyptian Pharaoh? Bo Nordh’s Ballerina “…strikes a pose that is indeed reminiscent of classical dance” (smokingpipes.com). Does it? Once for sale on this site was this rarity: “Tom Eltang: Smooth Arne Jacobsen Lamp Pipe (Snail), resembling a deeply bent Churchwarden at the end of which lies a generously flared Dublin bowl, …’Snail’ grade and even rarer ‘M’ designation.” What? Rattray’s “Beltanes Fire Grey half-bent Rhodesian/Bull Moose”? Of course, Nørding, Eltang, and Nordh have lots of company. Rovera’s Armony, Lirica, Melody, and Ritmica series; Ascorti’s Sabbia series; Big Ben’s Shepherds; and too many others to list here, but you understand what I am striving to convey.

Three examples, chosen at random, should suffice to illustrate the issue. Todd Johnson is a very talented artisan pipe maker, but the names he gives to his pipes befuddles me. His “Phalanx Circumcized [sic], Long-Shank With Jadeite [shank ring]” is one example. In ancient times, a phalanx was a body of armed infantry, and everyone knows what circumcised means.

Other Johnson pipes are named STOA Phalanx and Hoplite. Stoa is a classical portico or a roofed colonnade, and Hoplite was a heavily-armed infantry soldier of ancient Greece. The descriptors, I feel, do not conjure up visions of these pipes.

Constantinos Zissis describes his “Bewitched Crane” as follows: “To me, this tobacco pipe has also been a kind of exercise in geometry and balance, as—despite its asymmetrical shape and very narrow ‘bas’—it manages to stand, reminiscent of the crane standing on one foot.”

The Yeti: Smooth Eskimo (374).

According to the description, the Eskimo is another name for the Ukulele, but I think that a more appropriate shape name would be optimized aerodynamic, but that’s a bit awkward, right? Then there’s the Eskimo egg whose shape looks nothing like an Eskimo. Is an Eskimo egg different from a standard egg? I’m confused.

On cigarforums.net, tonkingulf asked: “I would think that there are more than one or two companies making skaters but cannot find any. Does it have another name?” “Any of the weird ‘artistic’ shapes, such as the Blowfish and the Volcanoes mentioned above. While any number of non-smokers might appreciate the appearance of a well-made classically-shaped pipe, only pipe smokers seem to like the oddball artisan funny shapes” (lawdawg, pipesmagazine.com). Belgian pipe maker Nick Ramaekers (trade name Massis) created the “1902 Alaskan Banker,” a blend of the large, flat surfaces of an Eskimo, the shank of a banker, and the shank facets of a bulldog.

Were many of these pipe names chosen at random, on purpose, do they have a sub-rosa meaning? It’s probably unintended, but it can confound and confuse a pipe smoker. It’s unlikely that any contemporary pipe-maker got his inspiration to name a pipe shape from this stoned community’s suggestion: “If you are stuck for ideas or are just too damn stoned to think straight, this bong name generator will give you a huge range of different bong names that you can use for your beloved bong” (nerdburlars.net). “Whether a regional term, a name from a tradition, or a personal term for your favorite device, bong names are a reflection of those who name them and use them” (hemper.co). Our community is bong-less.

Why do pipes need names anyway? Numbers could as easily serve the pipe maker’s purpose. Sam’s #456 should be as acceptable as Sam’s snail. Random’s Pipes, Wilmington, Delaware, were numbered, e.g., Random #14 and Random #37. (See “Random’s Stylized Bulldog,” glpease.com). For the U.S. market, German pipe maker Roland Kirsch keeps it simple: he numbers his pipes, i.e., “Roland Kirsch Pipe #8” (pipeshoppe.com). Letters of the alphabet would do just as well, I would think.

How do other industries name a product? Usually, it’s a series of steps that begins with describing what the name should represent, making a list, generating possible names, checking their background, and presenting the best-suited one, a name that will resonate with buyers. I don’t believe that anyone has bothered to follow this method in assigning names to pipes. To be clear, I do not know if these pipe names are copyrighted, but if they are, then I am just p_____g in the wind.

Summary, Conclusions, and…

I certainly don’t expect that anything will change, but highlighting all this should at least bring attention to the issue. It’s a free-will environment where a pipe maker can make whatever pipe shape he pleases and name it whatever he pleases. There are no rules to abide by. It’s an anything-goes, an age of call-it-what-you-will. In the absence of evidence, as you’ve read, some have ventured a guess, posited a theory, attempted an explanation. Here’s what Mark Twain said: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—‘tis the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.”

No one has a complete picture of the names assigned to briar pipes, no one knows the entire story. An exacting typology or classification system for today’s briars does not exist. There’s no industry pipe-shape-name playbook, nothing in print that approaches a comprehensive study. There is no U.S. industry-wide organization that sets standards or oversees the briar pipe trade as, say, Britain's Worshipful Company of Tobacco Pipe Makers & Tobacco Blenders, established in 1619 as a trade association and originally “tasked with regulating the manufacture of clay tobacco pipes.” Today, it is involved with all aspects of the UK tobacco trade. We’ve taken these pipe-shape names at face value; the names are too ingrained. The standards will prevail unless and until someone demonstrates a need to change them. Kim Tingley’s essay in The New York Times “Everywhere. Forever” (August 20, 2023) is about the per- and polyfluoroaroalkyl (PFAS) chemicals that are found in just about everything, sneakers and sanitary pads, pizza boxes and paint, furniture and fast-food wrappers, vinyl flooring and flamingos, and in hundreds of other everyday products. The CDC report conclusion about individuals exposed to PFAS caught my eye: “…insufficient evidence exists at this time to support deviations from established standards of medical care.” I have to say that this is also true about pipe-shape names.

I did not find the Holy Grail, or the Delphic Oracle, or the Wise Man, or Darwin’s On the Origin of the [Pipe Name] Species. Just like the tragic history of the search for the Fountain of Youth, I suspected that I would be unsuccessful in my search for the fountain of tobacco pipe phraseology. But it certainly wasn’t a waste of my time to research. It was a novel idea seeking a plausible explanation. I enjoyed comparing what most pipe smokers, pipe makers, and pipe sellers know about these names, but I didn’t find what I was looking for: answers to those Rumsfeldian known unknowns. That doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. It means that I failed to find them. And if such a study exists, it might be found in the archives of the NPA or the Tobacco Merchants Association.

I may have just been tilting at a windmill; much ado about nothing; a fool’s errand; the futile pursuit of ground truth; making a mountain out of a molehill; a dissertation about distinctions without differences. Or maybe the lesson learned is to leave well enough alone; don’t rock the boat; and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it? Will someone else research this little-studied aspect of briar pipe nomenclature? It’s a question without a knowable answer. This is a better question: is it a worthwhile endeavor? As long as factories and independent artisans produce pipes that continue to exhibit subtle or radical variations, permutations, alterations, or modifications that transform the appearance or structure of classic, traditional, or modern briar pipes, it’s futile to create a database of all shapes and their one-offs. It would be even harder to maintain in this age of freehand and offbeat pipe formats. It’s evident that such a framework is not needed. But if asked whether there is a need for such, some might say: TMI; “It doesn’t matter“; I couldn’t give a damn,” “I could care less,” or “Who gives a s__t?” It’s not a doomsday issue for the Trade or for pipe smokers or pipe makers that requires redress. Personally, there could be one unintended consequence for old timer and newcomer alike: staying current with this unsystematic, haphazard pipe shape and pipe-shape name terminology—a polite word for jargon—that can feel like messing with your mind.

After scrolling through several online blogs, I can say that there is confusion as well as confidence in what some folks have posted about both pipe shapes and their names. Some ask, because they are inquisitive, curious students of the art form, because pipe-shape history is a fascinating topic. Sadly, in every pipe book that includes a discussion about the briar pipe that I have read, there’s no chapter (or verse), no “tell all” section, no writer discourse addresses this issue, and with good reason: it’s an uninvestigated topic, and no author wants to conjecture, presume, hypothesize, or hunch it, and I don’t blame them. I’m inclined to believe that there never was a system for naming pipe shapes as they were introduced into the marketplace, because no one saw a need for one then, and certainly no one sees a need for one now. The Industry has survived and thrived without one, although I’ll quote a Manhattan Briar Pipe Company ad: “For years the public has been shown the various tobaccos to buy, but has been left unadvised about the much more important matter of the pipes to smoke them in.”

Our community consists of many experienced experts and many more neophytes and learners who are trying hard to become as knowledgeable. Are there answers that no one knows the question to? (G_d, I hate to end a sentence with a preposition!) I don’t want to dramatize this topic, but if an explanation exists, if there are answers, finding them would be the Holy Grail of Briardom. Rick Newcombe wrote In Search of Pipe Dreams, but I doubt that anyone would undertake writing In Search of Pipe Names.

Maybe it’s as simple as this: “And in the latter part of the [20th] century, advances in manufacturing and technology allowed for the creation of new shapes and styles of briar pipes, catering to the diverse tastes of pipe smokers around the world” (theeveningpiper.com). Writes Misterlowercase (pipesmagazine.com): “A similar book [like History of the Calabash Pipe] on the evolution and origins of briar pipe shapes would be totally fascinating.” I agree, but if not fascinating, it would at least be revelatory.

What is evident is that some traditional shape-names and some of those assigned to contemporary artisan pipes have something in common: many do not evoke a vision … the word and picture do not agree. Many are simply misnomers. It’s certainly not an effort to misbrand or mislabel. It’s not akin to what’s been said about tobacco: “As the use of tobacco had increased, it had been adulterated in every possible shape” (William S. Walsh, A Handy Book of Curious Information, 1913).

Early on, we learned that language is the expression of thought by means of spoken or written words, and words were descriptive of the things they named. Imprecise language leads to ambiguity and poor communication. I know that, often, words can’t adequately describe a lot of things. Two centuries ago, C. F. Keary offered this explanation: “When we have written the words cat, man, lion, what have we done? We have brought the images of certain things into our minds, and that by a form presented to the eye; but is it the form of the object we immediately think of? No, it is the form of its name…” (The Dawn of History: An Introduction to Pre-Historic Study, 1878). In The Collected Works of C. J. Cala (2013), the author describes holistic reality, acknowledging something quite apropos of pipes: “But people say, ‘Even if we ignore the names, everything still has a separate shape, a separate look, etc.’”

Searching for a uniform agreement about the origin of certain briar-pipe shapes and their assigned names revealed a (Tobacco) Tower of Babel, the biblical narrative to explain why the world’s peoples spoke different languages. In Genesis, the Lord was to have said: “Now the whole world had one language and a common speech.” And then, “Come, let us go down and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.” This may be the best explanation of the inconsistencies and disparities that I found in my research into pipe shapes and their names. However, quoting Teddy Roosevelt: “Complaining about a problem without posing a solution is called whining.” Unfortunately, I have no solution.

My counsel? Heed the mantra of Brandeis University in Massachusetts: “Never take know for an answer.” And in a post about Bulldogs and Rhodesians, JRobert (pipesmokersdens.com) said it best: “There is a generally accepted convention, but no requirement that anyone follow the convention.” Amen!