Creating Pipes From Morta

Finding and Harvesting Morta

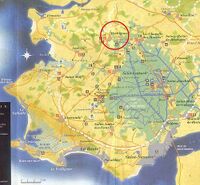

The process of obtaining morta is one of the biggest differences between the creation of a morta pipe and the creation of a briar pipe. Briar is an active industry emplying legions of workers and large mills for the most efficient harvesting and cutting of the wood, and a pipemaker can simply order pre-cut briar blocks by the bag at highly competitive prices. Some pipemakers, myself included, pay additional costs for purchasing handpicked blocks or traveling to the mills to choose their own, but this is still a relatively simple affair by comparison to the procurement of usable morta. In the map below, the large green area represents the Briere parkland:

The Briere

This area is roughly 16 miles across, and it is a trackless wasteland of marshes, fens, and open moors dotted with ancient standing stones. It is a vast area to search, and for most of the year it is inaccessible because the water levels in the crisscrossing aquaducts rise high enough that the open areas cannot be walked for morta. During the Fall, however, the water levels fall and during a narrow window from September to November one can (with wading boots) traverse through the moors. The morta lies under the moist surface packed in peat and mineral-rich clay, and can be 4' deep or more. It is found in the form of huge logs in the process of petrification due to the lack of oxygen required for the wood to rot, which it normally would have done long ago.

The morta is found by walking the soft earth and "poling" - driving a long iron spike into the peat in prospector-fashion, to see if it strikes the hard log of a tree. Once a tree has been located and identified by repeated spiking to confirm that it really is a tree and not a random rock, the area is marked and the search continues. Once several trees have been located, the digging begins and it is a hard and laborous process. The earth must be dug out to reveal the black logs and make it possible to remove them, and they must either be sawn into movable pieces or lifted out with a portable crane and chains. This requires the rental of a truck for transporting the large and heavy sections of wood, plus a lot of hours of labor carrying the stuff across the marshes.

Drying and Cutting

Once the morta has been unearthed and transported back here, it must be dried. This process is also rife with challenges, as morta dries faster than briar and if left exposed it will lose moisture too quickly and crack badly. The wood is kept covered in dark sheds for at least 2 years, and I will also be adding some end grain sealant and frequent re-moisturizing to this process in an attempt to control the splitting of the inflexible material. The logs are cut into radial sections and eventually moved into the workshop. A currently dry and usable log is visible in the picture below in the lower right shelf - each round section is ready to be cut into blocks, which will be further dried before use.

The large sections of morta are cut into small blocks on the bandsaw, where it is possible to inspect them closely and work around the splits that have appeared. Below you can see a few large chunks of morta ready to become usable blocks:

The cutting of the blocks will determine the layout of the radial grain, and blocks can also be cut specifically to allow for different tightness of rings. As with briar, each ring signifies a year's growth of the tree and tighter, more densely packed rings indicate wood that is the oldest within the tree. Below is a picture of a cut morta block with the sides sanded smooth in order to view the grain and plan the pipe design. Also visible is a small flaw. Morta is not prone to pits as briar, but does have its own share of defects including tiny splits and damaged areas.

Design Work

Design work for morta pipes is really little different from briar design, except that often the blocks are so much smaller that the range of available shapes is very limited. One unique challenge of morta is the length of the blocks - often they are quite short and square rather than longer than they are wide, as with briar blocks. This can produce a very "shankless" look if one isn't careful, and can also put the tenon tip too near to the tobacco chamber without very precise drilling and fitting.

I expect to produce a large number of morta pipes with bamboo shanks or other types of shank extension for the higher grades, to help overcome this visual stylistic limitation. Below I am holding various stem styles to the block to help visualize the look of the finished pipe, and thereby finding a shape that I think will look good and smoke well.

Finally I have a simple design that I think will look graceful, and I mark the drilling lines on the block and return to the bandsaw to make some pre-drilling cuts.

Sawing

I try to do a little more sawing of the block before the drilling begins, since it may reveal hidden flaws in the wood and it's better to see them now so that the block can be discarded than waste the time of drilling only to have to throw the pipe out later.

Once the block has been cut closer to shape, I inspect it again with a magnifying lens to see if there are any flaws visible, especially any splits which might run deeper into the wood and make the pipe unsmokable.

Drilling

The example below will show the lathe used for drilling, but we actually have several different drilling methods that we can use depending on the requirements of a specific design. In this example, the stummel is chucked into the lathe using a heavy-duty two-jawed self-centering chuck designed for pipemaking, and a forstner bit is mounted in the tailstock to flatten the end of the shank off. We can turn the shank or the bowl round if we want to, or leave this shaping to be done by hand later. Morta is much more difficult to turn smoothly than briar is, and it wants to chip quite badly. Thus far I have found it easier to simply do the bowl shaping later by hand, using sanding discs, though that method also has some unusual challenges with morta.

Next you see the pipe ready for the drilling of the tobacco chamber. I always drill the airhole first and drill down to it with the chamber bit in order to get it perfectly level with the bowl bottom - I've never been satisfied with the inaccuracy of "aiming" to try and get the airhole bit to hit the bottom properly. In the picture below, the bowl and shank have been turned on the lathe and tweaked with files, to no great result as the surface is too chipped to use without serious sanding by hand on the wheel.

Now, the chamber has now been drilled and checked for a good relationship with the airhole, and the pipe is ready for its detail shaping. The interior of the chamber is inspected with a magnifying lens once again to ensure that there are no hidden flaws which might compromise the durability of the material during smoking.

Detail Shaping

Detail shaping for morta is done much like it is with briar, though there are some differences. The big one is that metal cutting bits work much better with morta, and small reamers of various shapes are the primary tools I use with the rotary carver. Below is a picture of our detailing station where we keep all our hand files, rotary tools, and sanding wheels:

The pipe goes from the lathe back to the bandsaw where the corners are cut off and the shape is further roughed out to produce something like the picture below:

From here, the stummel is shaped almost entirely by hand and eye using the sanding wheels, drums, files, and the rotary carvers. One interesting point about morta is that it must be sanded with care, as it heats up strikingly (and painfully) with friction on a sanding disc. Anyone accustomed to the sudden burn from working a piece of metal held in the fingers will know what I speak of - the sanding goes normally when suddenly your fingers are on fire! The morta will become extremely hot but cool back down quickly, so the process of sanding and shaping requires more care in avoiding too much sustained pressure against the wheel. Morta is also much harder on sanding wheels and discs than briar is, and it will very quickly turn a new disc into a piece of smooth fabric.

Stem Work

Stem work was one of my big debates at the beginning of the morta project, because it was obvious that if I made all the morta pipes with handcut stems the combined labor would make even the tiniest ones cost $300. Since no one wants to pay $350 for a thimble with a handcut stem, I chose to compromise and split the stem work according to the sizes/grades of the pipes themselves, thus keeping the smaller pieces relatively affordable while providing higher-end collectors with the quality of materials and workmanship that they expect. Classic-grade pipes use very good quality pre-shaped stems, while Signature-grade pipes use handcut stems. Even in the case of the molded stems, however, there is a good bit of stem work to do. The bits are filed thinner for comfort, and the airholes are carefully opened to match the size of the shank airhole in order to maintain the proper flow of smoke without inducing condensation problems. All bits, whether molded or handcut, are also sculpted at the buttons to open the interior and allow easier pipecleaner insertion. Here I am doing just that, using a jeweler's bit that performs this task well.

Finishing

The single advantage that morta pipes have over briar in terms of ease-of-creation is in finishing - the coloring is all in the wood and the pipes cannot be stained. The black (or brown, or greenish-black) is the natural color of the material. Also, morta is open-grained, meaning that the rings are actually open to the air, resembling a series of small dots on the surface rather than coloring in the wood. This can cause hassles in buffing because the open rings want to pack with buffing compound and the surface must be carefully polished with a fine bristle wheel to remove any embedded gunk. The first step is still sanding, however, and the pipe is normally sanded to 600 grit on the surface. I use higher grits on the higher grade mortas, but it's not entirely needed as the surface does not take a high gloss like briar and going into the extreme levels of sandpaper grit is more wasted effort than actual results. Here I am doing the basic sanding on one of the first grade 3's.

The next step is buffing - first with brown compound which helps to reveal any remaining surface scratches and then with white compound to achieve a good gloss. Morta wants to maintain a satin finish - I have waxed and polished pieces to an extreme level but they quickly dull back down to a low sheen in use, and I've concluded that the material is simply so open that a briar-like finish isn't possible.

The final stage in making a morta pipe is to stamp it. I still stamp by hand without using jigs or braces, which is why my logos are often somewhat skewed (much like my mind) - it's the authentic Talbert touch that proves the pipe isn't a forgery :) Morta is a little easier to stamp than briar because the surface doesn't scratch as easily from fiddling the stamp around. There is one big problem with morta stamping however, and that is legibility - the open graining of the wood makes it sometimes challenging to clearly read the small stamping. It is likely that sometime in the future I will have a new set of stamps made specially for the morta pipes which will have larger and heavier lettering for better results.

Once the stamping is done, the pipe receives a final wax and polish and a new morta pipe is ready for smoking!

References

- ↑ http://talbertpipes.com/mortacreation.shtml, courtesy Trever Talbert and used by permission.