The Pipe Club. A History and Then Some

Exclusive to pipedia.org

Before I proceed, let me be clear about the pipe club in this essay. It is not about the Pipe Club at Aston University in Great Britain that encourages entrepreneurial spirit and offers activities to individuals interested in starting a business in a variety of different sectors. It’s not about Pipe Club—No. 1 through No. 5 tobacco blends from Kohlhase, Kopp & Co. It’s not about the Tahoe Pipe Club, because its sole focus is educating the public about water-quality issues in the Lake Tahoe area. It’s not about the club that promotes and teaches uilleann pipes, the Irish version of bagpipes. It’s not about this pipe club: “Before 1876 all attempts to prevent it [intercommunication] had been virtually abandoned, and the political prisoners had formed what they called ‘Water-closet Clubs’ or ‘Pipe Clubs,’ for social intercourse and mutual improvement. Each club consisted of ten or twelve members, and had its own name and rules” (“Russian State Prisoners. ‘Pipe Clubs of Political Prisoners,’” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, November 1887 to April 1888). And it’s certainly not about this pipe club: Macrotyphula fistulopsa (Typhulaceae), a fairly common, widespread fungus.

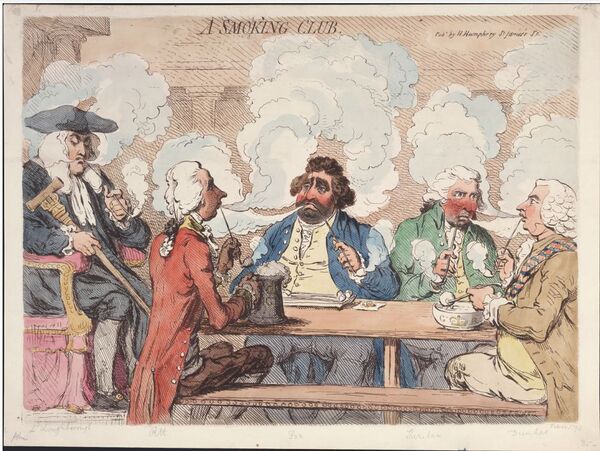

This narrative is about that place where men (and women) get together to enjoy the pleasures of pipes and tobacco. The pipe club has been a transformative phenomenon in pipe-smoking circles. It is not a recent event, as some newcomers to pipe-smoking might believe. Its appearance was in the 20th century, and its genesis is the smoking-room—the French called it le fumoir—in 18th-century England. Smoking-clubs had the same purpose as pipe clubs today: pipes, tobacco, camaraderie and conversation.

Why this topic? I’ve been writing about pipes and tobacco for more than 50 years, and my creative engine, along with the rest of me, is slowing grinding to a halt. I have not smoked a pipe for a number of years, and I miss that small pleasure. In these same 50 years, I never joined a pipe club, although I’ve had opportunities to do so. I am well aware of their burgeoning popularity throughout the country and overseas. I have written about one club, the Seattle Pipe Club (Pipes & Tobaccos, Spring, 2009). I now write about its origin some 400 years earlier when it was known as a smoking-club and to make some observations about today’s pipe clubs.

I’ve made every effort to present historical facts and events in chronological order and, in places, I ignored the chronology to include many colorful comments, salty snippets, and tawdry tidbits that shed light on these bygone smoking-clubs, because they were the topic du jour for at least a half-century. These are presented in the order of their publication date, although they may refer to an earlier time.

To begin, the upper classes of 18th-century England indulged themselves heartily in tobacco, reveling in the thick, luscious clouds of smoke. A country gentleman might join a private club that had a smoking-room. The gentleman’s club was the locus, par excellence, for manly conversation and relaxation, aided by the consumption of a good glass of beer or punch and a fine, long, slow-burning pipeful of tobacco. During Queen Anne’s reign (1702–1714), the According to Margaret Bertha Synge, A short history of social life in England (2020), The Twopenny Club had some strict rules: “Every member shall fill his pipe out of his own box. If any member swears or curses, his neighbour may give him a kick upon the shins. If any member tell stories in the Club that are not true, he shall forfeit for every third Lie one Half-Penny.”

In 1826, “Leigh Hunt [English critic, essayist, and poet] described with nostalgia the clouds of smoke that surrounded the community of pipe smokers in the early coffee houses. Yet Hunt associated pipes with drunkards, whilst cigars were the ‘mildest as well as the most fashionable form of tobacco-taking.’ For Hunt, cigar smoking was a private habit associated with the drawing-room. Otherwise, more genteel smokers gathered in male ‘smoking clubs’ or had to restrict their smoking to the alehouse. By 1800 it was noted with surprise how early eighteenth-century coffee houses had allowed smoking to be ‘permitted in the publick room’” (William Tullett, Smell in Eighteenth-Century England. A Social Sense, 2019).

The object of clubs is often asserted to be, the promotion of trade, human conversation, and the communication of curious and scientific matter; but, according to an old writer, he gives this opinion, that ‘most considerate men who have ever been engaged in such sort of compotations, have found, by experience, that the general end thereof is a promiscuous encouragement of vice, faction, and folly. …There have been clubs so designated is most certain; but the practice of smoking is too universal to misapply the term when speaking of clubs in general (Tavern Anecdotes, and Reminiscences of the Origin of Signs, Clubs, Coffee-Houses, Streets, City Companies, Wards, &c., 1825).

The Reverend George Crabbe penned a lengthy poem, “Clubs and Social Meetings” in 1845. I quote one segment:

A Club there is of Smokers—Dare you come

To that close crowded, hot, narcotic room?

When midnight past, the very candles seem

Dying for air, and give a ghastly gleam;

When curling fumes in lazy wreaths arise,

When the long tale, renew’d when they last met,

Is spliced anew, and is unfinish’d yet;

When but a few are left the house to tire,

And they half sleeping by the sleepy fire;

Ev’n the poor ventilating Vane that flew

Of late, so fast, is now grown drowsy too.

O think, of that den of abomination, which, I am told, has been established in some clubs, called the Smoking Room,—think of the debauchees who congregate there, the quantities of reeking whiskey-punch or more dangerous sherry-cobbler which they consume; —think of them coming home at cock-crow and letting themselves into the quiet house with the Chubb key… (“The Snobs of England,” Punch, or The London Charivari, Volume The Twelfth, January to June 1847).

And then you have the advantage of hearing such delightful and instructive conversation in a Club smoking-room, between the hours of 12 and 3! Men who frequent that place at that hour are commonly men of studious habits and philosophical and reflective minds, to those opinion it is pleasant and profitable to listen. They are full, of anecdotes, which are always moral and well-chosen; their talk is never free, or on light subjects. I have one or two old smoking-room pillars in my eye now, who would be perfect models for any young gentleman entering life, and to whom a father could not be better that intrust [sic]the education of his son. …But as for a Club smoking-room after midnight, I vow again that you are better out of it: that you will waste your money and your precious hours and health there; and you may frequent this Polyanthus room for a year, and not carry away from the place one single idea or story that can do you the least good in life. …Will you like to have that gentleman [Mr. Tippleton] for a friend? He has elected himself our smoking-room king at the Polyanthus, and midnight monarch (“Mr. Brown’s Letters to A Young Man About Town,” Punch, or The London Charivari, Vol. Sixteenth, 1849).

This is an observable Parliamentary maxim—when a Government is safe, the smoking-room fills; when a Budget has only to be puffed, its details are gone into over a cigar. The influence of the House of Commons’ smoking-room upon British history, has never been sufficiently recognised, and must be discussed some day (Edward Michael Whitty, The Derbyites and the Coalition. Parliamentary Sketches, 1854).

Thanks, however, to the changes time has wrought, moderation is now invariable amongst gentleman and they now take but a brief interval for tobacco, talk and coffee in the smoking or billiards room before they rejoin the ladies (Mrs. Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s Book of Household Management, 1861).

Nothing can be more singular to an English eye than one of those smoking companies; and never did we see a more curious one than here [Worms, Germany]. At the long table sat two rows of men, many of a remarkably heavy, shaggy, uncouth appearance, with rough heads of hair, and coarse pent-houses of bristly moustaches to their mouths. Each was armed with a long pipe, many of them so long that their heads reached down under the table. Along the stood small square decanters of wine, each holding about a choppin, or pint, and glasses with spills in them. Most solemn and heavy were the visages facing each other, yet loud was the clamour of voices, and stupendous the volumes of smoke (William Howitt, A Country Book, 1863).

The earliest description of a smoking-room is from the Victorian novelist Marie Louise de la Ramée (pen name Ouida) who idealized it in fiction: “…that chamber of liberty, that sanctuary of the persecuted, that temple of refuge, thrice blessed in all its forms throughout the land, that consecrated Mecca of every true believer in the divinity of the meerschaum, and the paradise of the narghille,—the smoking-room” (Under Two Flags. A Story of The Household and The Desert, 1867).

At any rate every one had left the drawing-room; one by one, smokers of every variety and every colour of smoking-jacket and of dressing-gown, had dropped into the before-mentioned sanctuary of tobacco, where, under sporting pictures and one or two foxes’ brushes, and shut off from the rest of the house by double baize doors, we formed a party of about half a dozen, round the cheerful fire which the chilly days of early October rendered quite acceptable. After all the members of the social community were supplied with cigars and large glasses, which contained various compounds of effervescing waters, and had settled into their chairs, we chatted… (Anon., An Arm-Chair in The Smoking-Room: Or Fiction, Anecdote, Humour, and Fancy for Dreamy Half-hours With Notes On Cigars, Meerschaums, and Smoking, From Various Pens, 1870).

Nor should we omit to make mention of the fact that a man who relishes his after-dinner cigar or pipe will find no more comfortable smoking-room in which to indulge his fancy than that of this excellent old hostelry [The Tavistock in London], whose history goes back as far as the first decade of the century. …Bed-rooms four and five storeys up, spacious drawing-rooms, where everyone speaks to his neighbour in a whisper, coffee-rooms with stout Corinthian pillars, smoking-rooms as empty and as dreary as the waiting-rooms of a railway terminus— these are the leading characteristics of some of the modern London hotels, and truth to say, they do not betoken comfort (Charles Eyre Pascoe, London of To-Day, 1885).

By the way, the pictures by Stanfield and Roberts were the means of the smoking-room being established at the club [The Garrick Club], when it was first founded in King Street, in 1830. For a long time smoking was not permitted in the house. Members who wanted a cigar either had to go into the street or wander in a strip of garden behind the house. Then they smoked in a shed in the corner of the garden, which was subsequently converted into a species of smoking-room (“London Notes,” The Book Buyer, May 1886).

When I visit them in the old Inn they take a poor revenge by blowing rings of smoke almost in my face. Once I was a member of a club for smokers, where we practised blowing rings. The most successful got a box of cigars as a prize at the end of the year. Those were the days (James M. Barrie, My Lady Nicotine, 1890).

Many of the smoking-rooms in the old hotels remind one of a bad specimen of a railway station ‘general waiting room,’ but those belonging to the newer undertakings are furnished on more comfortable lines, while the drawing rooms leave nothing to be desired” (“Inns and Inn Signs,” Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, March 1894).

When the Psi Upsilon Club moved into a new house recently it was found that a ‘pipe room’ had been set aside for members who wanted to burn their tobacco in that way. Heretofore pipe smoking had been against the house rules of this club. There are other clubs in New York that have pipe rooms, and they are popular. American men were conspicuous in England some years ago because they smoked nothing but cigars. Within the past few years, however, the pipe has been growing in favor, and there are many men in New York to-day who smoke a pipe, not because they enjoy it, but because they think it is good form. A globe-trotting Englishman was put up at a New York club less than ten years ago, and he availed himself of the privileges in a way that made English guests unpopular in this club for several years. His pipe was his most objectionable belonging, and he smoked it all over the club, to the great annoyance of some of the older members. On complaint, a house committeeman called the attention of the visitor to a rule forbidding pipe smoking in the club. The Englishman remarked that this was an amazing country, and was surprised to find that a man could not enjoy the same privileges in his club that he was entitled to in his home. But the pipe has smoked its way into many New York clubs since then, and the objections of its opponents have been overcome by the establishment of pipe rooms (The Shield. A Magazine Published Quarterly in The Interests of Theta Delta Chi, Vol. XI, No. 1, 1895).

After books, perhaps the most distinctive feature of the club [the Bodleian, Oxford, England] is our collection of pipes. In a large rack in the smoking-room—really a superfluity, since smoking is permitted all over the house—is as complete an assortment of pipes as perhaps exists in the civilized world. Indeed, it is an unwritten rule of the club that no one is eligible for membership who cannot produce a new variety of pipe, which is filed with his application for membership, and, if he passes, deposited with the club collection, he, however, retaining the title in himself. Once a year, upon the anniversary of the death of Sir Walter Raleigh who, it will be remembered, first introduced tobacco into England, the full membership of the club, as a rule, turns out. A large supply of the very best smoking mixture is laid in. At nine o’clock sharp each member takes his pipe from the rack, fills it with tobacco, and then the whole club, with the president at the head, all smoking furiously, march in solemn procession from room to room, upstairs and downstairs, making the tour of the clubhouse and returning to the smoking-room (Charles W. Chesnutt, “Baxter’s Procrustes,” Atlantic Monthly, Vol. XCIII, 1904).

I found an additional sentence from “Baxter’s Procrustes” in another book. It follows the last sentence ending in “…the smoking-room.”

The president then delivers an address, and each member is called to say something, either by way of a quotation or an original sentiment, in praise of the virtues of nicotine. The ceremony—facetiously known as ‘hitting the pipe’—being thus concluded, the membership pipes are carefully cleaned out and replaced in the club racks” (Abraham Chapman [ed.], Black Voices. An Anthology of African-American Literature, 2001).

[W]hen Thackeray wrote the story [Fitz-Boodle] smoking had not become the general habit it is to-day. No gentleman in those days was seen smoking even a ‘weed’ in the streets. Cigarettes were practically unheard of in England, and outside one’s private smoking-room pipes were tabooed. Men in Society slunk into their smoking-rooms, or, when there was no smoking-room, into the kitchen or servants’ hall, after the domestics had retired. A smoking-jacket was worn in place of their ordinary evening coat, and their well-oiled massive head of hair was protected by a gorgeously decorated smoking-cap (William Makepeace Thackeray, The Fitz-Boodle Papers and Other Sketches, 1911).

By the way, velvet was the ideal material for the smoking-cap, also called a smoking-hat or lounging cap, because the velvet absorbed the smoke and did not contaminate clothes. (Read “Smoking-Cap: In Colors,” Peterson’s Magazine, 1867.) For the gentleman-smoker, there was also the smoking-suit.

Nearly every man who goes out much has his smoking suit, and some worn by heavy swells are very elaborate and costly. I have heard of one that cost its owner the modest sum of £40. The code of the smoking suit was, according to this story, quite severely enforced by one’s peers. One suspects that the tale originated with the makers of such garments (San Francisco Argonaut, undated).

Mrs Daffodil’s Aide-memoire: Smoking suits, jackets, and caps were designed to keep the smell of tobacco, said to be offensive, particularly to the ladies, off the gentleman’s person. No doubt there were some households where smoking was forbidden and visiting smokers had to lie on their backs and smoke up the chimney, but it is also a fact that many ladies also enjoyed cigarettes in the privacy of their own boudoirs (Birmingham [West Midlands England] Daily Post, October 25, 1889).

After admitting the absolute necessity of allowing the members to smoke somewhere in the club, she continues: ‘To forbid smoking, therefore, is to exclude the men; to banish them to a separate smoking-room is to confirm and strengthen a bad habit, but allow them to smoke in a club-room, where they are amused and occupied, and the pipe will go out, which often leads to the discarding of it altogether’ (B. T. Hall, Our Fifty Years: The Story of the Working Men’s Club And Institute Union, 1912).

In the afternoon the gallant might attend what Dekker calls a ‘Tobacco-ordinary,’ by which may possibly have been meant a smoking-club, or more probably, the gathering after dinner at one of the many ordinaries in the neighborhood of St. Paul’s Cathedral of ‘tobacconists,’ as smokers were called, might have gathered “…to discuss the merits of their respective pipes and of the various kinds of tobacco—‘whether your Cane or your Pudding be sweetest.’ …These country smoking-rooms were known as stone-parlours, the floor being flagged for safety’s sake; and the ‘stone-parlour’ in many a squire’s house was the scene of much conviviality, including, no doubt, abundant smoking. …I [Lord Macaulay] have left Sir Francis Burdett on his legs,’ he wrote, ‘and repaired to the smoking-room; a large, wainscoted, uncarpeted place, with tables covered in green baize and writing materials. On a full night it is generally thronged towards twelve o’clock with smokers.’ …The late King Edward, at that time Prince of Wales, is said to have sympathized strongly with the defeated minority at White’s [a fashionable club], and to have interested himself in the foundation of the Marlborough; where, ‘for the first time in the history of West End Clubland, smoking, except in the dining-room, was everywhere allowed.’ By ‘smoking’ is no doubt here meant everything but pipes, which were not considered gentlemanly even at the Garrick Club at the beginning of the present century. Apart from social environment, there is a certain affinity between pipes and clothes. It is considered ‘bad form’ for a man in a frock-coat and silk hat to be seen smoking a pipe in the streets (George L. Apperson, The Social History of Smoking, 1914).

Joy reigneth in the hearts of many of the members due to the new rule accepted by the Board of Governors permitting pipe smoking in the Club. Just as the time-honored and historic art of pipe-inhaling seemed to die a dismal death along comes the proclamation of the Governors which is acting as an elixir of life. Pipes that for years have been accumulating dust and dirt in old garrots may now be seen daily in the lobby with slightly renovated appearance. Old curious, formerly used as momentos [sic] of the past, are now in actual service and may be seen dangling nonchalantly from the parted lips of distinguished N.Y.A.C. men. It should not be construed that pipe smoking had been abandoned completely during the preceding ‘dark ages.’ …It is now expected that the usual line of ‘pipe dreams’ will start at once (“Prepare the Way for Pipe Dreams,” The Winged Foot, January 1918).

In clubs, as in private houses, smoking required special permission, and a smoking-room was a place specially furnished with a minimum of textile hangings, and not unlikely to be supplied with the disgusting objects known as spittoons, and euphemistically designated cuspidors by retail tradesmen and American citizens (The Savile Club, 1868 to 1923, 1923).

At a few clubs there are still some curious and rather unmeaning restrictions. A particularly absurd rule that maintains its ground here and there, is that which forbids smoking in the library of the club. What more appropriate place could there be for the thoughtful consumption of tobacco than among the books? But after due allowance has been made for a few minor restrictions of this kind, the fact remains that smoking has triumphed socially all along the line of Clubland. We have travelled far from the days when a committee man could declare that ‘No Gentleman smoked,’ to the time when, for example, the large smoking-room at Brooks’s is one of the finest rooms in one of the most famous and exclusive clubs (Wilfred Partington, Smoke Rings and Roundelays, 1924).

George I, of England, built a fine smoking-room in his palace in Hanover, and he had similar smoking rooms made in his British palaces. The dour Carlyle, describing one of George’s English smoking rooms, said: ‘A smoking room, with wooden furniture, was set apart in each of his majesty’s royal palaces. They were for evening service, and were called Tabagees. Looking into one in the evening, we might see a high room, contented saturnine figures, a dozen or so of them, sitting around a large, long table, furnished for the occasion, long Dutch pipes in the mouth of each man, supplies of tobacco close to hand, a small pan of burning peat to keep the smoke wreathing. The smokers were in various moods—jolly, contemplative, discursive, and demonstrative. …The king, seated with his select number of friends, smoked his Dutch clay, and reaped his greatest of pleasures from the tobacco and pleasantries of his companions’” (Dr. Arthur Selwyn-Brown, “Pipe Smoking by Men Famous in Song and Story of Everyday World,” Tobacco, August 18, 1927).

In Western Europe the rituals of smoking, as in the smokers’ clubs in London and Berlin, were tied more closely to the socialization of individual smokers. Some of these clubs, such as those at the Berlin court…were quite elaborate affairs. … Most, however, were middle-class affairs. These clubs served coffee or chocolate, the two drinks of pleasure in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While the tamping, scraping, lighting and re-lighting of tobacco pipes did constitute a ritual, it was the context—the club with its conversation, libraries and meals—that provided greater rituals. (“Introduction,” Sander L. Gilman and Zhou Xun [eds.], A Global History of Smoking, 2004).

For the leisured bourgeois gentleman, however, the most glorified place of smoking companionship was the gentleman’s club. The club was mythologized as an idealized smoking utopia of rest, meditation, loungeful conversation and, most of all, sheer dedicated concentration on the joys of one’s cigar. Men came here to be solely in the presence of other men and their pipes or cigars (Matthew Hilton, “Smoking and Sociability” in Sander L. Gilman and Zhou Xun [eds.], A Global History of Smoking, 2004).

For example, a club rule may stipulate that we cannot bring ladies into the smoking room. If one quits the club, one can bring ladies into rooms where people are smoking. Therefore the rule is said to be hypothetical only, and thereby escapable. But is it really escapable? One still cannot bring ladies into the smoking room of the club even if one quits, so the rule is inescapable for all that. When an ex-member brings a lady into a room where people smoke, he is not violating the club rule so long as the smoking room into which he has brought the lady does not belong to the club. He could have done that even while still a member of the club. So his doing that cannot count as an instance where he has escaped the Draconian clutches of the club rules (Malcom Murray, The Moral Wager. Evolution and Contract, 2007).

It seems to me farcical, for instance, that in this twentieth century of ours, a rule made fifty years ago to the effect that ‘pipes shall not be smoked in this club,’ should still be enforced. Plenty of the younger members of the clubs where this rule obtains have endeavoured to rebel, but in vain. The Committee have solemnly pointed out to such free-thinking and independent spirits that their fathers and grandfathers did without pipes, they ought to be able to do without pipes too–in the club. Oh yes, they were at liberty, if they liked, to smoke cigarettes at five a penny all over the house, but never tobacco in a pipe, even if they paid half-a-crown an ounce for it (William Le Queux, The Mysterious Three, 2019).

All over Europe, and especially in England, the bourgeoisie adore regulating somebody or something, and the tendency remains long after members of this class have entered what are known as fashionable circles, and managed to obtain a hold upon the committees of exclusive clubs. In such a position, not a few of them have added largely to the number of rules, some of which in certain clubs are multiplied to the point of absolute absurdity. Occasionally, edicts of this kind possess a certain uncommon humour, as is well exemplified in a by-law, still amongst the rules of a certain club, which sets forth that ‘Members smoking pipes may not sit or stand in the windows.’ …In rooms, however, in which pipe-smoking is allowed, it is certainly not within the powers of a committee to define exactly where members shall station themselves whilst ‘blowing their cloud’ (Ralph Nevill, London Clubs. Their History & Treasures, 2021).

There were also pipe clubs in name only that had a dubious objective. “Frederic Raingold, junior, was in the hands of his friends at the Clay Pipe Club. This is an incubating establishment on Fifth Avenue, entirely supported by private contribution. Its object is to hatch and force that wondrous genus of brute creation, quite common to large cities, marked ‘clubman’ for identification if lost, strayed, mis-laid, or stolen” (The Illustrated American, Vol. XIII, No. 151, January 7, 1893). “The Clay-Pipe Club has developed into a Society for discussing social questions from as educational a standpoint as possible. The Society has been fortunate in obtaining good openers, who have generally managed to greatly interest and instruct their hearers” (Oxford House in Bethnal Green, 1894). “The Mansion House Council can develop a clay-pipe club, to settle, amid the fumes of tobacco, the deepest problems which beset the social reformer” (John M. Knapp [ed.], The Universities and The Social Problem, 1895).

“After dinner It was Prince Albert who conferred respectability on smoking by installing a smoking room at Osborne [Osborne House, a former royal residence, where a smoking room was built] on the Isle of Wight, to which the men could retreat after dinner” (Susan Storrier, Scottish Life and Society. Scotland’s Domestic Life, 2000). “After dinner, if you’re male, you will go with the other gentlemen to the smoking room, while if you’re female, you’ll accompany the ladies to the drawing room for coffee and conversation” (Michelle Higgs, Visitor’s Guide to Victorian England, 2014).

From these many passages it should be evident that the activity in the pipe-smoking rooms of the West was not much different from what took place in the opium dens of the East in the same century. And before I forget, the smoking rooms on many ocean liners of the period were lush affairs that had different amenities for different classes of passengers to assure segregation and privacy.

“It [Ye Olde Tavern, 161 Duane Street, New York] is a ‘hole in the wall’ built in revolutionary days, and has been used as an eating-house time without end. It has heavy oaken rafters which one can almost touch with his hand, hung with all sorts of mementos, and the walls are covered with old prints and pipe racks. The racks are filled with long-stemmed clay pipes, each bearing the name of the owner, so that the regular habitues always have their same smoke.” (The Sigma Chi Quarterly. A Journal of College and Fraternity Life and Literature, Volume XXVI, 1906–1907).

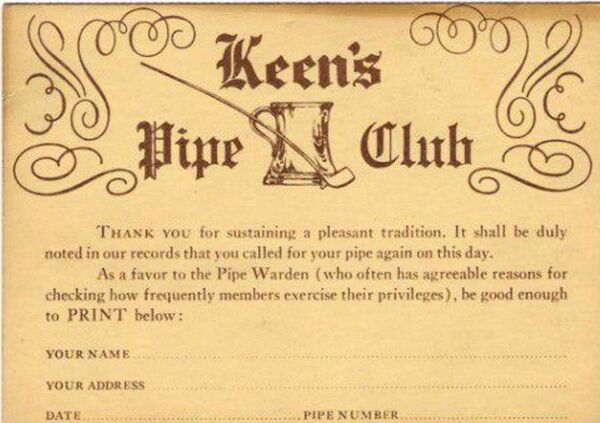

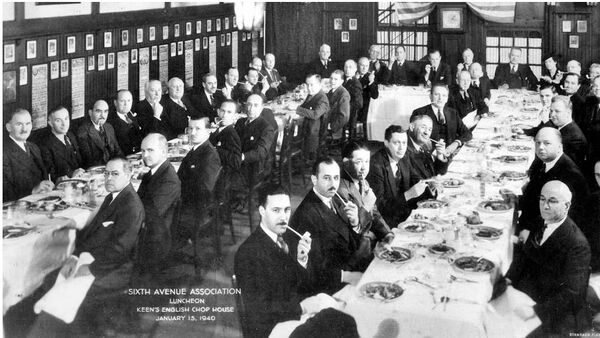

The most famous American public pipe club with a lengthy history is Keens in New York City. Before Keens was a restaurant, it was the Lambs Club—also written as Lamb’s Club—a famous theatre and literary group founded in London. Established in 1874, The Lambs Club was America’s first professional theatrical club for Broadway and film actors and actresses; its manager was Albert Keen. There are many comments as to how and when it began.

The Lambs Club became Keens when, in 1885, Albert Keen opened Keen’s English Chop House—now known as Keens Steakhouse—as a gentlemen’s smoking club that also served food. It’s the second-oldest steakhouse in the city. (The oldest is the Old Homestead Steakhouse that opened in the Meatpacking District in 1868.) Keens pipe club was established in the early 1900s with a display that may have replicated the concept of Ye Olde Tavern on Duane Street; some say that Keen adopted the idea from England. (There was a tradition in 17th-century England of travelers keeping their clay pipe at their favorite inn. Consider that one could not walk and, simultaneously, hold a churchwarden in his mouth; it was a pipe for sedentary contemplation.)

“Keens soon became the lively and accepted rendezvous of the famous. Actors in full stage make-up hurried through the rear door to ‘fortify’ themselves between acts at the neighboring Garrick Theatre. By the time Keens celebrated its 20th anniversary, you could glance into the Pipe Room and see the jovial congregations of producers, playwrights, publishers and newspaper men who frequented Keens” (keens.com). “Its low ceiling is lined with tens of thousands of clay churchwarden pipes, each numbered and carefully catalogued by a pipe warden so pipe boys would be sure to deliver the right smoking device to each one of the 90,000 members of the Pipe Club, a group that originated at Keens in the early 1900s” (Judy Gelman and Peter Zheutlin, The Unofficial Mad Men Cookbook, 2011). “Early in the early 20th century, the owners of what was then the Lambs Club restaurant/tavern began collecting long, thin-stemmed clay Colonial ‘churchwarden’ pipes. Tradition dictated that after you smoked your pipe in the tavern you gave it to a ‘warden’ to store for you, as they were so fragile they broke easily when transported. When you returned to the tavern, you asked for your pipe and the warden retrieved it” (Rick Browne, A Century of Restaurants, 2013). “The clay churchwarden pipes were brought from the Netherlands and as many as 50,000 were ordered every three years. A pipe warden registered and stored the pipes, while pipe boys returned the pipes from storage to the patrons” (1000thingsnyc.com). According to Esquire magazine (Vol. 11, 1939): “Also the pipe club members receive a plum pudding at Christmas…” James Conley, Keen’s service director and house historian, declared that the pipe club was active until 1978.

Read Bill Schultz, “A Pipe Dream Comes to Life” (The New York Times, March 2, 2012). Access keens.com to see the pipes of some of its illustrious members; theirs are kept in display cases up front, and those of the less famous are now attached to the ceiling; it’s probably the largest assemblage of churchwardens in the world; and patrons paid $5.00 each year to store their pipes. When a member of the club died, someone at Keens would break his or her pipe so that it would never be used again. (See the Conclave of Richmond Pipe Smokers later in this article for an explanation of this ritual.)

This might have been the only American department store with a pipe club. In 1939, “A new pipe club was set up in the Esquire Room restaurant, with pipes, tobacco, and a dark oak pipe rack all supplied free of charge by Gable’s [a department store in Altoona, Pennsylvania]. Members had 131 pipes and high grade tobacco like Prince Albert and Sir Walter Raleigh at their disposal, for use in the Esquire Room. The only requirement was that the members be regular patrons of the Esquire Room restaurant” (Robert Jeschonek, The Glory of Gable’s, 2019).

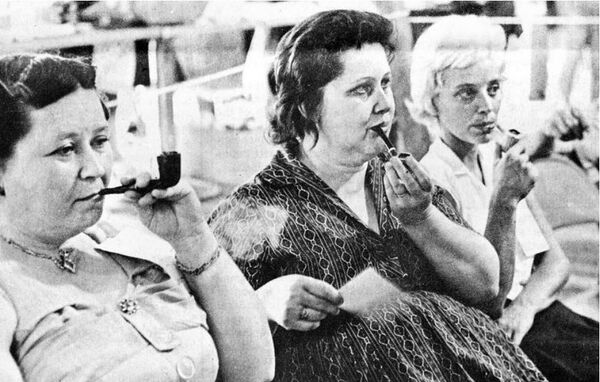

The earliest female club, the “Women’s Pipe Smokers Club,” was founded in 1926. The photo depicts its founders.

(The Merrilee Jones “Lady Pipe Smoker Club” is on Pinterest, and there’s a short black and white video clip, “Pipe Smoking Lady,” at British Pathé.)

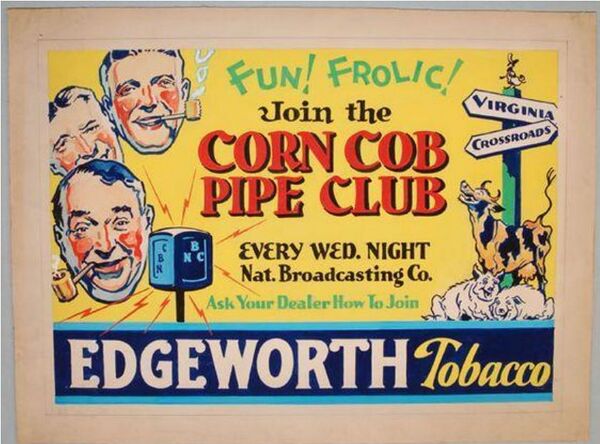

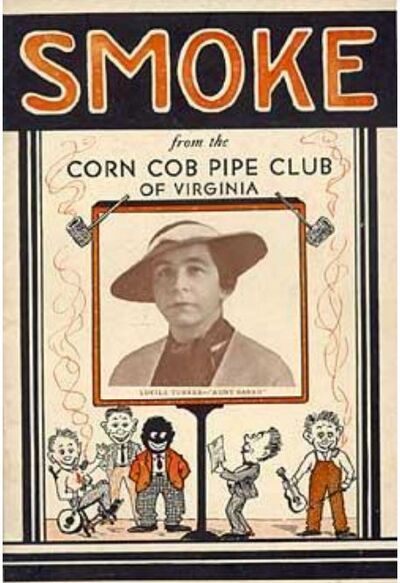

The Corn Cob Club of Richmond, Virginia, was probably the first of its kind. It published a slim monthly pamphlet, Smoke. The magazine claimed that there were 681 clubs in 37 states, the District of Columbia, and 73 affiliate clubs in several foreign countries. The first mention of the club appeared in “A Novel Method of Catching Sea Fowl” (The Railway Conductor, January 1908), but more often and much later in tobacco trade journals. The November 17, 1927 edition of Tobacco. A Weekly Trade Review, announced the broadcast of WRVA, owned and operated by Larus & Bro. Company: “10 p.m.—Corn Cob Pipe Club Dutch Gap Center.” The Club was on the air every Wednesday night at ten o’clock. In 1934, the station was New York’s NBC-WEAF. In that same year, the Club boasted more than 272,000 members nationwide with chapters in all 48 states. (A popular minstrel show sponsored by the Corn Cob Club with whites portraying the black characters, Watermelon and Cantaloupe, was broadcast on WEAF.) Unfortunately, the audit trail of this club seems to have ended sometime in 1935. I salute Pipe Smokers Den member MLC whose research effort, “Edgeworth’s Corn Cob Pipe Club,” is at pipesmokersdens.com.

On May 20, 1941, members of the Young Women’s Republican Club of Milford, Connecticut, got together to partake in the pleasure of pipe-smoking to demonstrate that smoking was not just an exclusive, collegial activity for men.

“In December 1942, Edwin La Fumee, Secretary of the Friends’ Pipe Club asked [Herbert] Hoover to send a used pipe for the club to display. First I must comment that La Fumee is the perfect name for a pipe advocate. Hoover graciously sent a ‘lightly used’ pipe to the club. Adding his stem to the ranks of pipes donated by such luminaries as: Jackie Cooper, Bing Crosby and Ronald Reagan [the actor, not yet a politician]” (Matthew Schaefer, “I Might as well Finish my Smoke…” hoover.blogs.archgives.gov). Unfortunately, I came up empty searching the Web for this club. George Yale, a tobacconist in New York City often advertised in Popular Mechanics in the early 1940s: “Free to all pipe smokers! A year’s subscription to our illustrated catalogs read by over 90,000 enthusiastic smokers. Collectors, connoisseurs, and pipe club members (my italics) will enjoy fascinating facts about briar, meerschaum, corncob, clay, odd pipes, tobaccos, blending, smokers’ accessories, etc. Send for your free copy today.”

Online searches yield the occasional mention of mid-20th century pipe clubs. Butler University, Indianapolis, welcomed a pipe club. In 1948, the university had an on-campus pipe club whose “purpose was to stimulate interest and appreciation toward pipe smoking and the collecting of pipes. Its members were selected from men who were known to be true pipe and tobacco connoisseurs. Activities included ‘smokers’ and outings such as a trek through a factory that specialized in custom built pipes. Various blends of tobacco were also displayed in Jordan Hall along with an exhibit of rare clay pipes” (Roger Boop, Fulfilling the Charter. The Story of the College Education at Butler University and More, 2008).

Search the Web and there is the occasional mention of a pipe club in the Press. In 1950, Lockheed Aircraft Corporation had a pipe club whose members got together to carve a briar pipe to send to General MacArthur, personalizing it with his initials and the five-star insignia. The Saturday Evening Post, Vol. 232, Issues 1-4 (1959) mentioned the Twynne Bryars Pipe Club of Manchester, England, and the Israel Pipe Club of the Central Police Station in Ramle, Israel.

If you want to read about all the pipe clubs that were popping up everywhere in the United States in the mid-20th century, you don’t have to look too far to know about their rapid spread. You need only thumb through all 52 issues of Pipe Lovers; just about every issue contained an article about the establishment of a new club and its planned activities. Here’s one example. In the January 1950 issue was this announcement: “Nation-wide club of lady pipe smokers announces five chapters from coast to coast. The Toby Pipe Smoking Club now has five chapters, with new ones being added daily; chapters include Toledo, Ohio, Beverly Hills, Miami, Florida, New York, Washington, D.C.” Vintage black and white photos of the Chicago Women’s Pipe Smoking Club in 1954 are online.

In the February 1947 issue of Pipe Lovers, it was suggested that a National Association of Pipe Clubs be established. In the August 1947 issue, it was proposed that this club be named the National Order of Pipe Smokers. In the March 1948 issue, The National Order was reorganized. Sometime between that month and July 1949, it became The International Association of Pipe Smoker Clubs and incorporated in Schenectady, New York. It is now under the auspices of the Arrowhead Pipe Club in Flint, Michigan.

This photo illustrates the participants at the first convention of the National Association of Pipe Smokers Clubs.

I may be the only critic, but the word “International” is a trifle hyperbolic. There are about a dozen member clubs and they’re all in the United States. Since 1949, it has hosted an annual World Pipe Smoking Contest and posted the World Pipe Smoking Champions on its website, but these winners are from these clubs. None have competed in the International Pipe Smoking Championship hosted by the Comité International des Pipe Clubs (CIPC) in which members of every pipe club affiliated with it, including members of those clubs belonging to the United Pipe Clubs of America (UPCA) can compete. More about the CIPC and UPCA follows.

This next pipe club was reported in the Montreal Gazette on April 13, 2019. “History Through Our Eyes: April 13, 1954, a pipe-smoking club.” The lead sentence was “Pipe-smoking as a club activity seems to have disappeared from the social landscape, but that was not the case in the 1950s.” Talk about sharing a puff, this is a 1954 photograph of members of the Maple Leaf Smoking Club partaking of the world’s “only known electric pipe.” (Pipe-smoking clubs may have disappeared in Canada, but they were popular elsewhere and for quite some time.)

If you want to know all there is to know about pipe clubs in the United States in the mid-20th century, there’s only one place to find it: Pipe Lovers magazine. Just about every one of its 52 issues contained an announcement about the establishment of local and state-level pipe clubs. For example, in the January 1950 issue: “Pipe Clubs: New Nation-Wide Club of Lady Pipe Smokers Announces Five Chapters from Coast to Coast. Well men, the women are forging ahead. They’re really doing something about starting pipe clubs—of women—exclusively! The Toby Pipe Club Smoking Club which was first announced in the October [1949 issue] now has five chapters, with new ones being added daily.”

Ethan Colbert wrote this for The Missourian, January 22, 2023: “The Photos Tell The Story: A look back to when pipe smoking enthusiasts descended on Washington” when the International Association of Pipe Smokers’ Clubs participated in its 17th annual convention and contest at the Washington Town & Country Fair in 1965. It was hosted by the Corn Cob Club of Washington, Missouri.

The oldest European collective is the CIPC, headquartered in Saint-Claude, France—the same city that hosts the Confrérie des Maîtres-Pipiers—that brings together pipe clubs from around the world for a slow-smoking competition. It was founded in 1973, when there were very few pipe clubs in Europe. Its mission: “We foster links across the globe in honor of friendship and to celebrate the fraternity of pipe-smokers across all borders.” There are now 30 national member clubs across America, Africa, Asia, Australia and Europe. As many as 400 or more participants, representing their national pipe clubs, attend the annual event.

UPCA was established in 2002 as a federation of U.S. pipe clubs, and is a member organization of the CIPC. Its current membership is 21 active clubs and 10 expired clubs; expired may mean that the club may no longer be affiliated with UPCA, but may still be an active club. And, like the CIPC, it sponsors both national and regional pipe-smoking contests in accordance with CIPC “Regulations for International Pipe Smoking Championships.” It oversees the annual National Pipe Smoking Contest at the Chicagoland Pipe and Tobacciana show and designates three awardees: national champion, international champion, and women’s champion.

Following the formation of the Pipe Club of Great Britain (founded in 1969, shuttered in 1978), The Pipe Club of London was established in the following year, 1970. Today, it boasts more than 400 members in “26 countries and visitors to this website from 145 nations around the world.” The UK Federation of Pipe Clubs coordinates all activity for these pipe clubs, as does UPCA for its member clubs. In 1997, Frederick Prevenslik authored a 32-page book titled The Cutty Pipe Club, which must have been about a British club, but I was unable to find it in WorldCat. In 2016, John Walker, a member of the Norfolk Pipe Club, published Pipe Club of Norfolk. The First 40 Years, 1973–2013.

This unsourced statement on the Web may be accurate and might explain the surge in pipe clubs across the United States. “The first sign of any organized group of pipe smokers came about in the early 1970’s when some of the pipe smokers would meet occasionally with their friendly pipe shop managers at various smokers’ homes. In 1977, Diana Silvius, owner of The Up-Down Tobacco Shop [Chicago], started a pipe smokers club for her customers.” This get-together could have been the incubator for many store-sponsored clubs that followed.

There are many Web lists of pipe clubs. To list all clubs in this article is futile—pipe clubs start and stop with relative frequency—and, by the time this article is online, the list would no longer be current. Furthermore, many tobacco shops have set aside a room for its patrons to gather from time-to-time for a smoke-a-thon, without necessarily calling it a pipe club, and there’s no way to know how many do this. Nonetheless, here’s a list of lists on the Web presented in no particular order. I’m not confident that I got ‘em all, but I don’t think that anyone has bothered to generate a list of all the active clubs around the globe. Come to think of it, why would anyone need or want such a list? (Online forums and newsgroups are mediums for pipe folks to be connected and communicate, but they are virtual, not in-person, gatherings, so they are not included in this list.)

- Synjeco.ch.

- Pipedia.org lists pipe forums, newsgroups, blogs, and pipe clubs.

- Smspipes.com.

- Pipesmagazine.com.

- Newyorkpipeclub.clubexpress.com.

- The Briar Patch directory of U.S., English and Canadian clubs (the briarpatchforum.com).

- Unitedpipeclubs.org.

- Cipc.pipeclubs.com lists national federations (countries) and clubs by geographic region: Africa, America, Asia, Australia and Europe.

- Pipemuseum.nl has a list of European pipe smoking clubs and guilds.

- George’s Pipe Smoking Pages (lepipe.it).

- Facebook: Pipe Smokers Club; The Europe Pipe Smokers Club; The International Pipe Club; Pipe Club Europe Pipa Market; Pipe Club; The Gentlemen’s Pipe Smoking Society; Pipe Smokers of America; Pipe Smoking; Pipe Smokers Club; The League Pipe Club; Corn Cob Pipe Club of America; YouTube Pipe Community; Briar Nation—Pipe & Cigar Club; Leaf Society; Pipe and Tobacco Society

- The Virtual Pipe Club is on YouTube.

- The International Peterson Pipe Club (petersonpipenotes.org.

- Instagram has a lot of member clubs.

If you click on “pipe club” at ebay.com, you know what you’ll find: pipes for sale. Etsy’s pipe club sells pipes.

A few clubs sponsor a publication for its members, and I want to acknowledge them. The Pipe Club of London began publishing a slick, biannual The Journal of the Pipe Club of London in 1993; it also has an online shop with lots of logo merchandise for sale to its members. The Pipe Club of Sweden’s full-color quarterly magazine, Rökringar (with an English summary), has been published since January 1992. The North American Society of Pipe Collectors, Columbus, Ohio, originally called the Ohio Pipe Collectors, has hosted a bimonthly publication since its founding in 1993. My pipe-oracle friend, Gene Umberger, informed me that the first publication was the Ohio Pipe Collectors Newsletter for two years, then as The Pipe Rack: The Ohio Pipe Collectors Newsletter for a few months in 1996, followed by The Pipe Collector since March 1997. The Sherlock Holmes Pipe Club has its Gazette. The Pipe Club of Lebanon, established in 2001, published its biannual Journal of the Pipe Club of Lebanon for just three years, 2006 through 2009.

The Christopher Morley Pipe Club in Philadelphia is named after the pipe-smoking American journalist, novelist, essayist and poet; he was a native son of the Keystone State. The Sherlock Holmes Pipe Club is in Boston. It might be a stretch, but there once was the Speckled Band of Boston, the oldest scion society of the Baker Street Irregulars that was founded in 1940, and The Adventure of the Speckled Band was one of Sherlock Holmes’s short stories. I’ve not contacted the Club, but it could it be the reason for its name. My personal favorite is the Conclave of Richmond Pipe Smokers, aka the C.O.R.P.S. (I know how it got its name, but I prefer that you ask Linwood Hines.) I single out this club because, on its website, there is a very poignant page devoted to its members who have passed away titled “Broken Pipes,” a term coined by the late Tom Dunn, who may have adopted it from the French, “casser sa pipe,” meaning to break his pipe or to die.

Now to comment about a few pipe clubs. This is the introduction to the Kearvaig Pipe Club of Scotland: “The Scottish bothy [a small hut or cottage], acting as a kind of de-facto last ‘speakeasy,’ offers one of the last, if not the last, public indoor spaces where pipe smoking is legal; if only because it would be impossible to police without a helicopter. …So, quite simply, the Kearvaig Pipe Club (KPC) was formed for chaps who like to smoke their pipes in bothies. …Since the inaugural meeting, KPC membership has gone from a handful of pipe-puffing oddballs and misfits to a bigger bunch of oddballs and misfits.” And that of the John Hollingsworth Pipe Club, Birmingham, England: “A group of like minded people with a love of pipes and pipe smoking, who like to meet and put the world to rights, sometimes over a nice bowl or two.” How about the exclusive and elite Lords and Commons Pipe and Cigar Smokers Club? The Sons of Two Sicilies Smoking Pipe Club is so named, because most of briar pipe artisans and craftsmen are situated in southern Italy and Sicily, the ancient Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Words matter…even for pipe-club names. A century ago, pipe-club names were transparent, uncomplicated, usually the place names, such as Long Island’s Bridgehampton and Sagaponack Smoking Club or the Jacksonville (Florida) Pipe Smokers Club. Today, they’re clever, cute, and sometimes hard to decipher. Ohio has some interesting ones. The Wharf is an online pipe club sponsored by the Wharf Tobacconist in Beavercreek, Ohio, that posts informative articles online, such as this, “The History of Pipes.” Over-the-Rhine is a Cincinnati pipe club that’s named after its location; Over-the-Rhine is the downtown area of Cincinnati. The Cow Town Pipe Club is in downtown Columbus, Ohio, named so because, at a time, Columbus was called a cow town. The Scoundrels Pipe & Cigar Club is in Bath, Ohio.

The Pig’s Eye Pipe Club Parley in Minneapolis must consist of members who may often express strong disagreement. The Southern Fried Pipe Club is in Nashville, a city known for its outstanding southern fried chicken. California’s Sacramento Pipe Collectors Assembly is abbreviated SPCA; hopefully, it doesn’t get mistaken for the other SPCA. The Furniture City Pipe Society in Grand Rapids, Michigan, is so named, because Grand Rapids is known as the furniture city. The Pocono Inter-mountain Pipe Enthusiasts (PIPE)—very clever!—is in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. How about the Aromatic Pharts Pipe Club of Charlotte, North Carolina? (I can smell the burley!) Are the members of the Heretics Pipe Club separatist smokers? Do the members of the Silent Smokers Pipe Society commit to a vow of silence? Christian Pipe Smokers? This one’s easy. The website explicitly states “This group is for folks who smoke TOBACCO pipes or cigars who are also Christians.” The Pipe and Beard Club? I wonder if you can you join if you’re clean-shaven? The Viking Pipe Club of Saint Louis? Perhaps it harkens back to the Viking Club founded by J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon in the 1920s. I am stymied by Pale Blue: The Collective Draw Pipe Club of Boise, Idaho, so I left a message asking for clarification; maybe I’ll get an answer. The Twins Pipe Club of Londonderry, New Hampshire, is affiliated with the Twins Smoke Shop & Lounge in that city. Why “Twins”? The owner has a twin brother! According to its online description, the Shelby County Hoarders of International Tobaccos of Birmingham, Alabama—abbreviated S.C.H.I.T.— “…is designed to be the drunken obnoxious uncle of the UPCA family. This is a pipe and tobacco club for people who don't like clubs. If you like to smoke pipes while making lewd and off color comments, welcome!” The Saints & Sinners Pipe Club of Calgary? Was the club’s name an original idea or was it inspired by the New Orleans restaurant by that name, or the pub in Ormond Beach, Florida or the one in Cincinnati, Ohio, or a line of or hair products, or the TV series that ran from the 2016 to 2022, or sinnersandsaintsdesserts.com, or from several books with that title? The online Smoker’s Club is not what you may think it is; it sells smoking tools, such as stash jars, grinders, rolling papers, apparel and accessories. The Danny Boy Pipe Club is an online pipe seller whose club you can join for $25 for one year.

Through time, authors of both non-fiction and fiction have used smoking room as a catchy title. There are many books in both categories, but only a few are relevant to this topic: Richard Doyle, The Smoking Room at The Club (1862); Cope’s Smoke Room Booklets, a series of 14 pamphlets from Cope’s Tobacco Plant, Liverpool, was published between 1889 and 1894, an assortment of literary works from various author that eulogized tobacco and smoking, but were not specifically focused on the smoking-room; Francis Aveling, The Philosophers of the Smoking Room: Conversation on Some Matters of Moment (1907); James Stanley Little, Stories for the Smoking Room. Humorous and Grotesque (1911); and C. E. Radclyffe, Round the Smoking Room Fire. A Collection of Sporting Adventures and Yarns (1933).

These online articles are relevant:

- “The Smoking Room. A Victorian space reimagined” (bowhillhouse.co.uk).

- “Smoking room” (en.wikipedia.org).

- Cynthia Roman, “Smoking Clubs in Graphic Satire and the Anglicizing of Tobacco in Eighteenth-Century Britain” (cambridge.org).

- “Casa Vicens Gaudi is continuing the restauration of its most iconic room: the smoking room” (casavincens.org).

- “The rise and fall of the smoking room, from essential feature to long-gone relic” (countrylife.co.uk).

- Tristan Bridges, “Smoking Rooms—Unintentionally Providing Space for Gender Inequality” (inequalitybyinteriordesign.wordpress.com).

- Jack Bettridge, “Smoking Rooms of the Gilded Age” (cigaraficionado.com).

- “A Pig, a Dog and an Urchin” by Hallywyl Museum (artsandculture.google.com)

See the collection of images from Wendy Sullivan, “British Smoking Room” at pinterest.com.

In 2016, Tobacco Business Magazine asked: “Should Your Store Host a Pipe Club?” “…because B&M shops often are exempt from indoor smoking bans, they become a natural place for a pipe club to meet.” Often, that place is called a smoking lounge. Some stores have already answered the call.

Thinking of starting a club? Guidance on how to organize and launch a local pipe club can be found at smokingpipes.com, unitedpipeclubs.org, and iapsc.net. There’s an exchange of comments about pipe-club leadership on pipesmagazine.com. Tom Wolfe of the Seattle Pipe Club had posted this warning on the UPCA website: “That old saw about success in the restaurant business has never rung more truly than with pipe clubs. Finding a good location for meetings is one of the hardest parts of making a club successful. Constantly changing where and when you will meet is going to hurt attendance and can be the downfall of many clubs.”

I want to mention pipe-smoking on campus. This is an illustration from Boston University’s 1943 Hub yearbook. The University’s Terriers are the school’s athletic teams. (see right)

There was very little in the Press about college students and pipes in the last half of the 20th century because anti-smoking, not pro-smoking, was the cause célèbre in newspaper editorials, but I found this article in the Sausalito News, August 22, 1962: “College Man Still Favors Pipe Smoking.” (The 1964 Surgeon General’s 1964 Report on Smoking and Health claimed that pipe smokers lived longer than other smokers) Then, on February 20, 2009, The Wall Street Journal posted Mary Pilon, “The Latest Thing They’re Smoking in Pipes on College Campuses: Tobacco.” According to no-smoke.org, most local and state smoke-free laws do not include college or university campuses. I’m not interested in statistics but, if you’re curious, you can read about the prevalence of tobacco use on campus at jamanetwork.com.

On June 19, 2014, Marcus Jones posted “Why Don’t People Smoke Pipes Any More,” stating that, after becoming involved with pipe smoking, some college students were saying, “Now, I am an intellectual college lad.” Well, that may have been the comment of a few effete campus nerds. Four years later, Alonzo Kittrels (“Back in the Day: Pipe smoking was social and intellectual,” The Philadelphia Tribune, May 19, 2018) had this to say: “While I have no image of any of my friends being in this type of setting, I do have an appropriate and relevant statement related to pipe smoking that comes from a piece I read some time ago which I have paraphrased as follows, ‘I smoke pipes because it makes me appear to look intelligent even if I cannot recall where I left my automobile keys.’”

The times they’ve been a-changin! Recently, a few schools of higher learning have adopted liberal policies. A cigar and pipe social club is one of the student activities and organizations at Milwaukee School of Engineering. Purdue has a pipe and cigar club. Wabash College has a cigar and pipe club. The Order of Collegiate Pipe Smokers is Central Michigan University’s pipe club. There’s a student pipe club at Wake Forest. Check out The Collegiate Cigar Community (columbia.edu).

Finally, don’t forget to read “College Class Pipes” (pipedia.org). It’s a great story by Brian Robertson about a college tradition of the past.

A few odds and ends to wrap up this story. In the first-class smoking-room on the Titanic, male passengers could congregate, socialize, discuss matters of business/politics, smoke, drink, and play games of chance, except on Sundays. Le Fumoir is a trendy (no-smoking) café, salon de thé, cocktail bar, and restaurant in Paris. The Smoking Room is a cigar and hookah bar in College Park, Maryland. The Smoking Room was a British TV sitcom in 2005-2006. James B. Twitchell (Lead Us Into Temptation. The Triumph of Materialism) dislikes malls and writes: “The Tinder Box is a giant humidor”; and “Abercrombie & Fitch is a men’s smoking club.” “Well, Baltimore used to have a pipe club, where the jobbers, as you gentlemen are sitting here, would meet once a week in the hotel at lunch and discuss prices of pipes, and what was being done with the pipe in the city.” This quotation was from a 1950 interview in The Study of Monopoly Power. Hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives … about the steel industry.

And I add this for giggles to close out this lengthy story. Did you know that the Federal Government had classified the smoking room? This is how it appears in capital letters in the Official Gazette of The United States Patent and Trademark Office, Vol. 1273, No. 1, August 5, 2003: “FUMARI. FOR GENERAL SNACK AND DESSERT BAR SERVICES; SMOKING LOUNGE SERVICES, NAMELY, PROVIDING A SMOKING ROOM FEATURING HOOKAHS, FLAVORED TOBACCO PRODUCTS, CIGARS, AND SMOKING RELATED PRODUCTS (U.S. CLS. 100 and 101). FIRST USE 12-13-1997. FUMARI is in Class 42—Scientific, Computer and Legal Services.

Like Bugs Bunny, “That’s all folks!”