Thunér Pipes

Ronny Thunér - Pipemaker by Jan Andersson

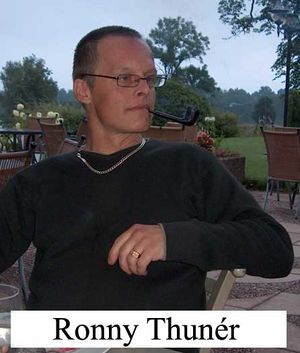

Ronny Thunér is youngest among the Swedish pipemakers and started making pipes in the beginning of 2005. He early proved to be very talented, and he has got a lot of help to learn the job properly from some of the very best pipemakers such as Bengt Carlson, Love Geiger, Martin Vollmer, Anders Nilsson, Tom Eltang and Soren Refbjerg.

In the following open-hearted story, Ronny tells us about his entire life, which has not been easy, and how he became a pipemaker. It is a strong story, so please read it carefully.

An Odyssey by Ronny Thunér

THE PIPE DREAM THAT ENDED A NIGHTMARE

Sometimes in Sweden’s long summer evenings, I lay aside the tools of my trade and gaze over the placid lake and the trees beyond. I listen to a rhapsody of silence. Then, slowly, I light my pipe.

And as the crisp air becomes scented with the smoke of rich tobacco from far away lands unknown to me, I smile quiet thanks to whatever mischievous gods or faeries of the waters and the forests also thought to hide nuggets of briar in parched earth and to disguise a majestic plant as drab weed.

The magical marriage between root and leaf, I muse, must surely have been made in some Valhalla.

You see, it saved my life.

This is no romantic overstatement, but explaining its literal truth does not make for a pretty story. And it’s more painful to tell than it is to hear.

It would be cute and easy to say that my life started when I broke my battered but beloved old pipe and, whilst seeking to replace it, I accidentally stumbled into my craft. To an extent, that’s true, and I’ll tell the tale later. But the whole truth must begin with a tear-away child who grew to become an outcast, living – always one step ahead of the law – in a murky underworld of drugs, fear and unspeakable violence.

The boy was born in 1968, and almost from the day he took his first steps, his parents and all those around him believed he must have been the spawn of some devil. The boy was Ronny Thunér, me, and with those first steps, I was already on the path to prison and psychiatric wards.

I have snapshot recollections of early childhood; my father shooting his air gun in the cellar, the horrendous car crash that took away his mind when I was just four years old and left him a remote and helpless cripple. One day, after seventeen years in an institution for the severely handicapped, he remembered my name.

Full and lucid memories go back to when I was a tiny thug of just six, standing at the side of the road, waving to motorists as they drove by. Those who didn’t wave back had a brick thrown through their windshield just before I spun on my heel and ran for cover. Even had I realized I could have killed those innocent folk, I’m not sure I would have cared.

Another childhood game for me was poking fun at the security guards in the local mall with their London Bobby-style pointed helmets. The stones I threw with all my might to dislodge that funny headgear didn’t always find their mark. There were injuries. So what?

In desperation, my mother confined me to the house under lock and key. She was a prisoner there herself; nobody would volunteer to look after a vicious child like me, not even for a few minutes. She couldn’t risk taking me to the shops or to visit friends or relatives. I was beyond control. Over the years, the poor woman was always teetering on the brink of full mental collapse. And she did suffer major nervous breakdowns because of her wayward son.

That’s when I learned to escape. I’d overcome whatever crude security measures she’d put in place to confine me and break out into a world where I could invade building sites and start up the motors of machines and cranes. I’d somehow manhandle the wheels of massive bulldozers and cause untold damage. I was never caught by anyone other than my mother, but local builders soon learned the need for security patrols.

I became the well-known local terror. I’d ride my bike around rooftops and dangle from seventh-floor guttering for fun. I had no friends because everyone else was totally crazy. Of course, the truth is that I was crazy and I had no friends because other kids and their parents were terrified of me. I hardly ever slept. I was just too full of wild curiosity and destructive energy. The general feeling was that I was simply rotten to the core. A hopeless case. Anyone who spared me a thought beyond this knew there was something very, very wrong in my head. But what?

You see, I was a lifelong sufferer of severe Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – ADHD – a clinical illness generally unknown when I was in my formative years in the ’70s. It would be decades before doctors discovered that I was the victim of a dark neurological condition.

Over recent years, it’s become clear that ADHD in its many forms and degrees of severity is one of the more common psychiatric illnesses. In extreme cases like mine, it manifests itself in wildly anti-social behavior, violence, a death wish. It produces junkies and killers. And modern professionals are on the alert for it. Psychiatrists and psychologists now realize that I was suffering from a world-class, but treatable, version of the disorder. Back then, I was simply labeled evil.

So things didn’t end with childhood naughtiness out of control. Not by a long chalk. I went from bad to worse.

I turned the classroom into a daily hell for teachers and other children. I had a good brain and pulled high grades, but I was disruptive and inattentive and what I was learning was actually learned outside school, the result of my own burning curiosity. So the teachers and I pretty well gave up on each other in seventh grade when I discovered drugs.

Yes, I was just twelve years old when I found I could score amphetamines easily from small-time local peddlers who preyed on the schoolyard. For the first time, I saw the world from a different perspective. The pills brought me to a calm and focused state and this strengthened my warped belief that I was the only sane person in a world of mental defectives.

I started to take refuge in nature and would run off into the wild countryside like a demented hermit. I felt bound to the woods and the lakes and found more predictability and friendship in birds and animals than I ever could in my fellow humans. In the wilderness, I was secure. Secure, but withdrawing ever further from society.

The grip of drugs became tighter until I couldn’t struggle free, even had it crossed my mind to try. It would be another twenty-three years before my condition was diagnosed, I went into treatment … and that broken pipe triggered my recovery and opened the door to a fresh and constructive life. Those years were miserable and squalid. I lived in a world of desperate addicts and dealers, who carried knives, pistols and shotguns as casually as if they were fashion accessories. Often, I’d stare down the barrel of a gun myself. I didn’t care. I was going to die anyway. I’d meet violence with violence and explode. I’d bite and claw and blood would flow. I’ve got scars all over my body from knifings, most of my bones have been broken in fights at one time or another.

No hospitals for a junky. I’d treat myself with whatever I could lay hands on; carpet tape or even superglue to close open wounds, bits of wire and scrap wood to splint a broken arm.

I was bloodthirsty and manic. Even in a world where insanity was the order of the day and sickening violence and murder were regular and unremarkable events, I was feared. I became an outcast of outcasts. It seemed the police were forever on my tail. I’d hide and dodge to escape them. I saw them as the enemy … which is, I believe, how they saw me. Three times, I was caught and slammed behind bars for crimes tied up with the violence and drug culture of the world I haunted like an angry ghost.

Police, judges, social workers and other knights of society knew something was not right, but they stopped short of trying to discover exactly what. And every time I was released from prisons, suffering more and more from my secret illness, I would scurry home to the shadowy backstreets to score drugs.

Inevitably, after my third jail term, the hunt for me was soon on again. I tried to make myself invisible and lurked in hidden corners. But I was caught … thankfully.

I was sent to a penitentiary where I slept four hours a week and burned up energy in the gym eight hours a day. Guards and nurses could clearly see there was something desperately wrong. A psychologist was called in. He took me out of the penitentiary to a clinic for three days of tests and evaluation.

At last, my ADHD was diagnosed.

I was over thirty years of age.

The condition had been well researched by then and it was possible for doctors to gauge the severity of my case. On a scale of 1-55, I topped 50. I had lived all my life suffering from an acute and treatable sickness … and nobody had known it.

My psychologist recommended immediate treatment with a type of medication called centralstimula. But the authorities were reluctant to give such a powerful drug to someone with my history of abuse. So when I was released, I was still receiving no treatment. I fought to stay clean of drugs, craving help and feeling like sonar without a converter. I was being strangled by the tangle of bureaucratic red tape delaying my admission to a clinic for the medicine I so desperately needed. After four months, I broke down and slipped back into illegal drugs.

This time my personal Dark Age would last three years. I became wilder than ever. I was as cold as ice. I had absolutely no remorse or feelings for anyone who happened to cross my path.

The word was out that the police were looking for an excuse to remove me from the civilized world – to put me behind bars for the rest of my days. Who could blame them? I had become an unholy menace.

Meanwhile, my intake had reached lethal proportions. The police would take random urine samples on the street, and they found I was popping enough amphetamine to kill anyone else. But a side effect of my ADHD was that my ever-hyperactive body would burn them up. I survived - just.

Then came the day when the level of drugs in my bloodstream was so high, it literally went off the scale of their measuring instruments. They marched me to a doctor who was, coincidentally, associated with my original psychologist – the man who first diagnosed my condition – and he reaffirmed that I was suffering from a severe form of ADHD and needed help.

He went out to bat for me. He pestered and argued until one treatment centre grudgingly agreed to take me in and administer the medicine they’d all been so reluctant to prescribe to a hardened junky. I spent two years there. And that’s where I turned the corner with judicial use of medicine, unbounded care … and that broken pipe I told you about at the start of this long story.

For many years, I’d been a pipe-smoker and had one battered old briar that had been my only friend during my time on the run. One day, the stem broke. I forced the plastic casing from a cheap ballpoint pen into the shank by way of repair. It didn’t work.

Contrary to foreign fanciful thinking, pipe-smoking isn’t big in Sweden. All I could lay hands on to replace my poor pipe was a tacky basket case that had been gathering dust in a local tobacconist’s shop. It was truly disgusting.

I was allowed limited access to the internet at the treatment centre, so I surfed the web and bought two cheap and simple hobby kits to try my hand at making my own pipe. The experiment was a disaster. Huge flaws appeared in the briar and reached all the way through the tobacco chamber. Neither pipe could be smoked.

But my disappointment was tempered by a strange and unfamiliar enthusiasm that had taken hold of me. I know now that’s when the briar bug bit. The start of my recovery. The start of my passion to create. The start of my new life.

I wrote to the Pipe Club of Sweden, who immediately responded kindly and with encouragement, giving me the names of reputable briar suppliers. They also suggested contact with other Swedish pipe-makers and put me in touch with giants like the world-renowned Tom Eltang and Soren Refbjerg, who’s been a master carver for four decades.

The generosity and help showered on me by the greatest professionals fuelled my new dream of becoming a pipe-maker in my own right. Before long, valuable information and advice was pouring in from experts all over the world, and I got to work with what crude tools I could scrape up.

With a few rough examples clutched in my hand, I approached the principal of an adult education centre to ask how I might study and train to gain the rare Swedish Diploma in pipe making. He was intrigued and decided to do all he could to help.

Soon, the wonderful Bengt Carlson saw my early work. He was impressed and offered himself as my personal teacher, artistic evaluator – mentor. My treatment centre directors agreed to sponsor the work and provide the basic machinery and raw materials I would need in my development. The deal was that I would pay them back over a period of time from income I dared dream would come from the sale of my work.

Within months, I was visiting study and practical workshops in Denmark and southern Sweden where experienced carvers would report back to Bengt. My rapid progress surprised even me. I seemed to have been born with a gift and I blossomed with the unstinting help and encouragement of those I considered heroes.

The world took on a new shape - and it was the shape of a uniquely carved bowl with a perfectly matched and elegant stem. I would wander into the country with my girlfriend, Davina, and spend hours, quietly staring at a tree or a rock or a stream or a bird. Designs, straight from the nature around me, would fill my mind. Sometimes, I couldn’t wait to get back to my workshop and would take a whittling knife and, there and then, carve out rough bowls in a piece of wood I’d picked up at the side of the trail.

With every thin shaving, another flake of my old and terrible life was being shed to reveal a little work of art.

It wasn’t long before I was invited to a special meeting of the Pipe Club of Sweden to exhibit. It’s an experience I’ll never forget. Some of the best pipe-makers in the world were there. There were no secrets; techniques for pipe-making and heart-wrung innovations in carving and engineering were shared as freely as handshakes among brothers.

I was just an apprentice. You can imagine my excitement when the masters of the craft were so impressed by my work that they arranged to hold a week-long workshop where they could each tutor me in their individual skills.

After a lifetime of being an outcast, I had been accepted into a brotherhood of sensitive, true artists. By the end of the week, they counted me as one of their own. I felt something I’d never felt before; trust in others and the love of a family. I had friends and I had a future.

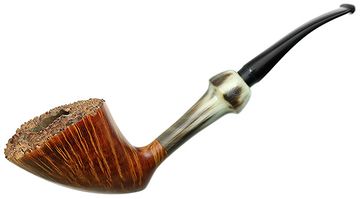

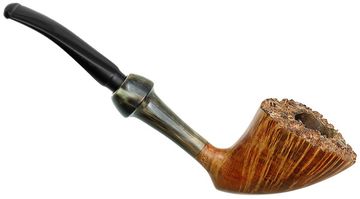

- Ronny Thunér with Horn Shank, Courtesy Dennis Dreyer Collection

The doctors had warned me that medication was only part of the cure for ADHD. The other part, I would have to find for myself. And I had. Drugs and degradation, solitude and violence became a fading nightmare as I threw myself with all the energy I once squandered on destruction into my new life as a junior member of this tightly-knit fraternity of artisans.

Soon, word was getting round that I was someone to watch. My work was being shown all over the world. The internet was a massive shop window. I could hardly believe it when I sold my first pipe - then another - then another. Letters and emails of praise started to dribble and then to pour in. Of course, I had to master practical skills for producing classic shapes, but the proportions of bowl and stem seemed to come naturally. I learned how to perfect lines and flow and to produce a finish that would stand up to the scrutiny of even the most powerful magnifying glass.

Most of all, I learned something I’d never known before – patience; the art of reflection, of total absorption in and focus on a task.

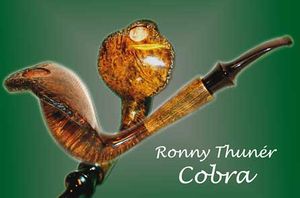

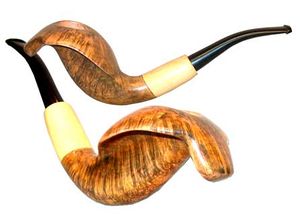

Before long, I was also working on unique freehands that were inspired by what I’d seen on my country rambles and in my mind’s eye. I invented The Cobra – usually a long-stemmed, wild snake of a pipe that looks set to strike. Perhaps it’s a form of recognition of my past – the settling of an old score with my violent and unpredictable self. Then I came up with the idea of the rusticated stem that can give the pipe a look that suggests it might have grown from the very earth.

I started to painstakingly select ancient plateau briar from the arid Mediterranean hills where it develops best, and to allow the intricate grains to shape my ideas. Now, I can take a hunk of root and actually see, concealed within it, like a bird in an egg, the very pipe that’s singing to be freed. I don’t work on a piece of wood; the truth is the complete opposite.

By the time I had my official pipe-makers’ diploma (passing with the highest grade possible), I was already making something of a mark. I’d built up a small cult following in various international pipe-smoking circles and a respected retailer in the USA actually opened a special store to showcase my work. My pipes are now being smoked in distant places I once barely knew existed.

Every cent goes back into briar and equipment and to repay the loans that got me started. I’m a pipe-maker now, but I have a long way to go - perhaps just a mile or two beyond as far as I can see.

I’m out of the treatment centre in Dagoholm – the place where, as recently as July 2004, I trashed the first floor in a frenzy of ADHD, but where I’m now considered the model of proof that there is a cure.

I live and work in a simple little rented house in the middle of a forest. And as I look out onto that placid lake with my pipe in hand and Davina at my side, I don’t fuss over what might have been had my illness been diagnosed earlier. I contemplate the future and the society of man – and the place I am determined to earn as part of it.

Would that those thousands of other troubled souls out there, whose pain has not yet been recognized by doctors, could have my good fortune.

Lady Luck has smiled on me. Perhaps she smokes a pipe.

Contact Information:

Email: mailto:simplunique@yahoo.se The Pipe Tart is a dealer for Ronny's pipes: http://www.thepipetart.com/thuner/Ronny_Thuner_pipes.htm