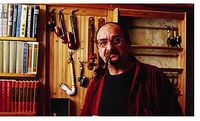

Vladimir Grechukhin

Introduction

Vladimir Grechukhin is one of the master pipe makers from Russia. Living and working in St. Petersburg, he first began working with, and studying under, Alexei Borisovitch Fyodorov when he was just eighteen-years-old in the 1970s. Fyodorov was considered by many to be the master pipe maker of Russia. Learning from the master came easily, as Grechukhin had been working with wood and other mediums since he was a child. He took well to understanding design and execution with briar and ebonite.

His pipes are excellently made out of briar and ebonite with the occasional accent of boxwood or black palm. Mainly chubby and compact in form (which we all love), these are beautiful pieces that are designed and made to be smoked. Grechukhin’s pipes feature hand turned vulcanite tenons, which is a testament to his craftsmanship. Each stem is carved from high-grade ebonite rod and the bits are equally comfortable and thin. Courtesy, Smokingpipes.com

Vladimir Grechukin, The New Clasics Master

Courtesy, Tobaccodays.com

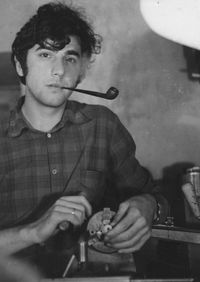

At 63 years of age, Vladimir Grechukin may in fact have the largest amount of design wisdom that I have ever encountered in any pipe-maker. This statement is not made simply due to the amount of years he has lived but definitely due to the experience he has been able to absorb throughout this time as you will soon read about. Grechukin has not only absorbed an immense amount of design wisdom, he now has so much of it, that he is in fact creating his own design philosophy. I was initially drawn to him because of a very particular, ground-breaking pipe design he created. Because he made this radical design, I naively saw him as a revolutionary, a separatist from the traditional shape pipe movement. After meeting him and getting to know him however, I was so pleasantly surprised to come away with a far different idea, that of a greater appreciation for the traditional approach to pipe making & those basic and most fundamental building blocks related to general pipe design principles. And it is upon these building blocks, which this pipe-maker constructs all of his work, much of it in fact creating a brand new interpretation of classical pipe-making.

Vladimir was raised in communist Russia. At the age of 12, the communist system decided that his life vocation would be in the arts. The communist system placed him on that path and until the age of 18, Vladimir studied art compulsively. In communist Russia, one in fact has little choice but to study compulsively however, the very rigid education system under which he received his design training was in fact cultivating within him the best building blocks that any designer could ask for, to properly approach their craft. He learned all facets of art. Including painting, sculpture, sketching and you name it. They taught it to him.

There was a specific method and approach to design for everything that Grechukin learned. Each art had it’s own system of rules on how to approach a specific artistic task. Grechukin learned every conceivable design methodology that was available to be learned and more importantly, he learned how an artist is supposed to approach and engage the design process properly. Although communism as we all know failed, the one thing it did very well was teach people, in whatever subject, extremely thoroughly and for that high-class design education, I as a pipe collector who enjoys looking at Grechukin’s work, am thoroughly grateful.

Almost immediately, Vladimir fell in love with pipes. Somehow, the entire idea of creating a functional instrument appealed to him. He felt a strong connection to the act of making a pipe, mainly because he says: “It is my work, it is my pipe, it is my hands that are making this item. This type of personal freedom and at the same time responsibility, was thrilling to me.”

His teacher, Alexei Fyodorov, is described by Grechukin as more of a pipe-making pioneer as opposed to a full-fledged pipe making master. “Fyodorov was not on the level of Sixten for example, not even close.” Grechukin tells me. “You can however make an analogy to Fyodorov and Sixten in the sense that they were both pioneers.” Grechukin continued: “Fyodorov made all sorts of pipe shapes before, during and after the war. Whatever the world of pipes was at that time, Fyodorov definitely had full mastery of all of it’s aspects. He was an exceptional teacher and he allowed me to realize what briar’s potential was.”

Then came the 90’s. The berlin wall fell, communism was beginning to crumble and new ideas began flowing into the country. It was at this time that Vladimir took a break from pipes and focused his attention on something new, the graphic arts. In Vladimir’s own words: “We had absolutely no internet and very few computers at that time, however I kind of pushed myself into these new areas mainly because we now had the freedom to make our own decisions and my curiosity wanted to learn more about graphic art design.”

Vladimir grabs me by the shoulder and asks me to listen attentively, telling me: “You have to remember David, during the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s I had absolutely no competitors. There was nobody else making ‘creative’ pipes. We were all following a system of making pre-determined shapes. It was all the same. Without competitors, I was obviously not able to grow at all. Yes, I was getting many compliments all the time but this was life under communism. The compliments did not feel real to me. And so, when communism collapsed and we had the sudden flow of new information into our country, I immediately got curious about the graphic arts and seized upon the option to learn new design information. It was part rebellion, part something new for me to do. I jumped on the idea to enter an area where other people were working hard and making new creations.”

Vladimir’s comment above cannot be understated by any amount. Those readers here who have lived in freedom for their entire lives, know not what it means to be told how to think and told what to do, day in and day out for your entire waking life. And as the collective pipe-world stares in awe at some of the amazing pipe art coming out of Russia these days, you must always acknowledge the idea and imagine the emotion that come with having one’s chains taken off. I can only imagine it as a massive explosion of sudden freedom. Both something new and curious and previously unknown. For some Russian pipe-makers, it is as if they want to leap off the Grand Canyon with their new found freedom. For a pipe-maker like Grechukin however, he took a more conservative path, which in my mind, highlights his professionalism to the craft. But the fact remains, Russians were chained for most of their lives and the new found freedom they have recently received is still being processed inside them each and every day.

Vladimir truly enjoyed his time in graphic arts. It opened his eyes & mind to new ideas, both from within himself and that of other people. As more and more information began to freely flow in the Russian country, Vladimir was slowly exposed to the greater depth of creativity that existed beyond Russia’s previously closed borders. After soaking up as much of the graphic arts world as possible, a decade later, Vladimir returned to pipes. This time around however, with all the new freedom he now had at his disposal, he was determined to start from zero again. He tells me: “I had hoped to start with a fresher, less restrictive perspective, yet still find a way to remain true to the design methodology that I learned in my past. There is nothing I value more than the design methodology my teachers taught me”

When Vladimir discusses this ‘design methodology’, he is describing the process he learned as both a young art student and as a pipe apprentice under Fyodorov. That is the proper application of a set or system of methods and rules, which regulate the discipline of making pipes or any given artistic endeavor for that matter. Vladimir follows these design rules religiously in all of his work and it is these rules which give him his pipe-making foundation. It is from this methodology that all of Vladimir’s work begins and ends.

Vladimir discusses the methodology as if it was written in stone. He says: “You have to make the lines look refined. You must have clear and distinct proportions through out the entire pipe. It is an absolute must to follow all of the basic design rules because anything else is just fantasy.”

Vladimir says: “I learned how to design within a methodology and because of this I approach pipe-making in a professional way. A professional pipe-maker will not say that he was lucky to create some shape. If you know a system and you know how to properly approach a task, you simply know it and all you can do is build upon what you know. Finding new things, looking for places to break the rules, experimenting and searching in that manner, this is not really a part of my methodology.

Grechukin: “Doing something new for the sake of doing something new, usually ends up at a dead end. A lot of monsters get born by approaching design this way. Most especially in art.”

Grechukin's Goals When Working

Grechukin describes his style as pipe realism. He treats the forms, space and color in his pipes in a manner that emphasizes and corresponds to actuality as much as possible. He wants his pipes to connect to what it is our eyes see, through our ordinary and basic visual experience. This is the complete opposite from abstract or speculative design. Vladimir wants to represent things as they really are or better said, as he perceives reality is dictating, they should look like.

From this definition, Vladimir takes it a step further and demands, as he says it: “That the pipe smoker and the pipe itself, dance together in harmony. There has to be a connection to the person, the face and obviously the mouth, which will hold the pipe. This harmony between the pipe and the person must exist because we are automatically creating a relationship between these two objects, each time a pipe is lit up. I cannot fantasize about the connection between pipe and man. We all already have a frame of reference that already exists, the human face. This is the frame that I work within and in my opinion, when you work within this scope, it is much harder to achieve the goal of a perfect pipe, when compared to those pipe-makers that are full of fantasy.”

Fantasy VS Realism

While it may sound like Grechukin is a closed-minded artisan, this is far from the truth. I asked him how he explains art in pipes and I describe to him my personal desire to see a balance between old traditional ideas and new ones, delicately coming together in harmony to create something new and interesting to look at and not looking like the “monsters” he describes above. He tells me: “Between classic and freehand shapes, between what we understand & what we don’t understand, there is no concrete line breaking the two and separating them. Things that people know and are comfortable with and understand, they do not actually conflict with new ideas or new designs. The idea of conflict itself is a manufactured idea, an absolutely stupid human thought and it is fully manufactured. We have to acknowledge that what people today call ‘Classic Shapes’, were once considered Experimental.”

Grechukin continued: “At the turn of the century when we received the bulk of what we call traditional shapes today, all of them were thought to be odd back then. Same thing with Denmark and Sixten. It’s all a repetition, the same thing happening time and again but people unfortunately fail to realize this.”

Grechukin goes on: “The world changes and change is normal. I change, times change and I start to like different things. All of us experience this process, it is very normal. Now with fantasy in pipes, one has to ask themselves, at what point can one fantasize with a pipe and still call it a pipe? A pipe is used as a smoking instrument, is it not? And if your not placing that item in the first place during your creative process and rather in the second place, everything becomes much more difficult. And then, if you place such a pipe to your face, well, the only thing happening is a masquerade.”

It is difficult to argue with that type of logic. Vladmir Grechukin clearly has placed pipe-making for himself within a certain type of pre-defined box, with clear constraints and rules guiding the rough placement of that box’s borders. This pre-defined rough box that he works within however, is filled with so much design wisdom, that each time he pushes the box out a little further, he does so without interrupting our sensibilities in a negative way. Somehow the box remains whole. The box continues to look square, rather than some abstract geometric shape. Grechukin has mastered the art of planting new pipe design ideas in a gentle and very refined manner. Something that in my opinion, only a true master can do.

I have no choice but to ask him about some of the ‘crazier’ pipe-makers that are out there and inevitably our conversation comes to that of my friend Misha Revyagin. Grechukin discusses him by saying: “I love seeing art that comes from the person and their soul. Whether I personally like his work or not, absolutely does not matter on that level. I actually don’t even have the right to comment negatively about anyone’s work, most especially if that work is coming from such a special & different place. Honestly David, at the end of the day, Wow!, the amount of respect I have for Revyagin, a pipe-maker who takes such big leaps is immense. The fact that he lives his life like this and expresses himself like this, this is the most important element for me. This is what is important.”

I prod Grechukin further and ask him to discuss some of the ‘monsters’, (as he calls them) that the pipe-world produces. He tells me: “Some paths that some pipe-makers take can be a little naïve. There are some pipes that people shouldn’t smoke because they lack functionality or it is missing some aesthetic. Also what I don’t get is, at what point, can a pipe leave it’s basic realm of understanding?” Grechukin directly asks me: “Isn’t this a tough question? How far can we actually take the design and still call it a pipe?”

It is here that I describe to Grechukin that this very question is a part of my personal search as a pipe collector. I tell him about my constant desire to find just the right balance between old, traditional and known design ideas and having them merge together, in perfect harmony, with some new idea. With the end result not looking like a monster but rather like the right & proper new step in pipe evolution. I then remind Grechukin, that this is exactly why I came to him in the first place.

Grechukin responds to me by saying: “Yes, you can make the pipe a little longer here and a little shorter there. Overall, with small changes, the pipe can still function organically well with the person. But there are some pipes, where that organic connection to the person is missing. Whether I like it or not, is not important. My words cannot be part of that process. Because I myself know that I don’t know everything and if I say I do, I am automatically limiting myself from looking at new ideas. I can tell you though, that when you look at a pipe, as it sits in the mouth and you look at it in a mirror. You start to see the organic elements I am talking about. The connection between the pipe and the human is an important element to me.”

Grechukin extends the idea and says: “Right now the tendency in pipes is to not focus on small nuances. Small, gentle and slight deviations (from regular pipe design) are no longer being taken. Today, the fad is to take a big jump and a big leap and the small nuance is no longer. It is now an immense nuance.”

Grechukin concludes the discussion with Revyagin by saying: ” I am happy that he is expressing his soul. I am happy that he can see his ‘hidden stuff in the closets’ talking out loud.” It is clear that Grechukin respects those types of artists to no end and he loves looking at their work & acknowledges it’s contribution to the community. For himself however, it is not a path that he wishes to partake in.

The Grech aka The Chopper

And now we get to the main reason for my attraction to Vladimir Grechukin. Grechukin created a shape that distinctly alters the way we imagine the basic design of the pipe. It was a rather simple yet stunning modification that he made. Most revolutionary innovations are in fact simple and minor adjustments. Grechukin simply placed the bowl of the pipe further back towards the shank. The bowl no longer sits in the center of the bowl massing. This allows the tobacco chamber to lean back which automatically creates an immense feeling of forward momentum on the front part of the bowl. The front of the bowl is automatically elongated, leaning & stretching back to reach the drawn back tobacco chamber. The pipe is both leaning back and lunging forward at the same time. The best analogy I could find is to that of a chopper. The custom built motorcycles that mimic this idea.

The Grech mimics the design of the famous American Chopper Motorcycle. Both leaning back, yet thrusting forward at the same time. The results are in my eyes, absolutely astounding. While at first glance it may appear misaligned, upon closer inspection, you see that it is in fact, perfectly balanced. This is where the ‘Master’ portion of his work comes in. Making something different look absolutely normal & proper.

I ask him to tell me the incredible story of how he came upon this shape but to no avail. There is no ‘magical process’ for him to describe to me with this pipe. He tells me gently, as if he is preparing me for heartbreak due to the lack of excitement surrounding the facts: “David, you as an interviewer and art lover, must already know this. Any project, any design, any artistic work, it is always bigger in the eyes of the audience, not the artist. Other people always want to see ‘more’ in the art than what the artist see’s. I just saw the shape in the briar one day and I did it. It happened intuitively, there is nothing more to say.”

He told me that he found some pieces of briar where the grain seemed to be off a little and he decided to follow those particular lines that day. As he proceeded to let the briar guide his hand he noticed that the center was off. The center was heading the ‘other way’. He followed the grain, made the design and found that it worked from an engineering perspective. At the same time, he found it to be very nice ‘aesthetically speaking’ and off it went from there. He played with it for some time before finding the right balance to the shape. He reminds me that: “If you don’t balance out the design, it will be un-harmonious. Whatever you experiment with, conceptual or not, the basic design rules must still apply!”

And there you have it. Grechukin created a new silhouette for a pipe. A new shape. The kind of silhouette that in my opinion should now sit on the shape chart. Similar to the placement of the reverse calabash silhouette, which very recently made it’s way to new pipe shape charts coming out of Europe. Do more shape charts need updating?

The Grechukin 'Chopper' shape My personal admiration for this shape cannot be overstated. My personal search for just the right balance between something new and old has been found with this new silhouette. Grechukin applied the maximum amount of ‘rule-bending’, yet he still retained a strong connection to traditional values. This type of work, in my opinion, is the perfect example of the best type of ‘proper’ pipe evolution that we could ask for today. This shape is destined to be a ‘new classic’.

As is the usual with any strong design idea, it is absolutely not limited to any particular type of shape. The design concept can be applied to a whole assortment of existing pipe shapes. From Bulldogs, to Tomatoes to Dublin’s to Acorn’s. The idea has so much strength, it carries so much ‘design weight’, that it can travel with ease into numerous pipe shape applications. This design idea definitely passes the ‘wide range application test’ with very high marks. Pipe-makers the world over are already beginning to incorporate the design into their work and we will soon be seeing much more of it.

You Always Have To Experiment

On the discussion of experimentation, Grechukin describes his vision for growth and how to sustain that growth on a consistent basis. He tells me: “The mastery of something does not travel along a straight line. It does not follow some pre-existing path, most especially once you are considered to be a Master. It can be different for other pipe-makers but for me, in my view, it does not look like a rising line on a graph that reaches a point and you eventually stop at a plateau. For me it is all about that exact motion however it happens in steps. You get to a certain point, great. Now it’s time to do something different so you can get to that new point with a new idea.” I feel very close to Grechukin and the words he says. Not just in pipe-making but in life as well. The idea of constant growth is a great philosophy to follow. If you truly want to improve your craft, applying a certain formula, a set of design rules as Grechukin follows, your view will always improve the higher you go. The strong foundation is however an absolute requirement for such growth.

Grechukin completes the idea by telling me: “So what if some pipe-maker made some great and amazing new shape. Very good! They should enjoy it and play with it. They should stay on that particular plateau, explore it and so on. But once you have finished with that shape, then you keep going with another shape and do the same process over again. But now apply that same process with what you have learned and this now gives you a new perspective for each new step you climb. The higher you go, the greater your overall perspective becomes.”

As you review the catalogue of Grechukin’s work, it is impossible not to see this ‘constant growth’ that he speaks of. You can truly see the step by large step growth that his pipes are and have been taking. It is this distinct quality of Grechukin that allows him to look at something old and find an appropriate new way to approach and re-create it. Grechukin is definitely leading the way of defining the new classics of pipe shapes.

Working With Other Pipe-Makers

When he works with other world class pipe-makers, he tries to incorporate their perception within his. He tells me that this is the best way for two masters to work with each-other. He goes into detail telling me: “I try to merge our thoughts and understand them both. How they think and see is crucially important to me. And then, I do my best to interpret their understanding. When the audience looks at the joint work in the pipe, they should feel that two masters made this pipe. It should be a perfect overlap of two philosophies.”

This is another example of what is important to Grechukin. He operates at a higher standard, far above the “me, I, myself” point of view. He is operating under the general design aesthetic principles and doing his best to have this be his only guide. No matter which other pipe-maker he works with, from Former, to Tokutomi, to J. Alan to Eltang, he forces his hand to be guided by this design philosophy, seeing it as his duty and his responsibility. As you look at the work he does with other pipe-makers, once again, it is clear to see this philosophy in action.

Final Thoughts

Pipe shapes are in a constant state of evolution. My personal view is closely aligned with Grechukin’s, in that it is the small nuances which should be leading the charge when exploring new ideas. This is mainly because the pipe smoking public has a certain degree of difficulty in accepting drastic and dramatic change & I am myself such a person. If we can look ahead, 10 or even 20 years down the road and if we try to imagine where pipes will be and what type of shapes we will define as ‘classic’ in the future, I imagine that much of what we see in Grechukin’s work today, will be sitting among those definitions. Bravo Grechukin, you truly are the Master of the ‘New Classics’.

See also Grechukhin: Vladimir Grechukhin "The “Mind, Honour and Conscience” of Pipe Design in Russia" (article from Cigar Clan Magazine)