Ye Olde Tobacco Box, Jar and Tin. Bygone Pipe Smoker's Accouterments

Exclusive to pipedia.org

You are about to enter the time machine of tobacco history. I haven’t addressed this topic since “Four Hundred Year Transition: From Tobacco Box and Jar to a Pocket Roll Pouch” was published in The Antique Trader Weekly in 1977. After 50 years, it’s time to revisit this subject with a fresh eye and new information. This tutorial is for the pipe-smoking and -collecting community of pipedia that may not be wholly familiar with their history.

Tobacco boxes, jars, and tins are the most diverse, wide-ranging category of tobacciana. They are smoker’s accessories that pretty much have lost their utility today. They’re impractical for many reasons, the most obvious of which is their material, weight, bulk, and inability to keep tobacco fresh. Years ago, the tobacco box and jar were as ubiquitous as the ashtray. It’s unlikely that either will see a revival; I don’t think that anyone is going to miss them.

As you read, consider that the recent concept of cellaring tobacco—no one had thought of it then—was an impossibility, given the types of containers that were available to the smoker; tobacco storage at home was not in a carefully engineered and consistent environment. Not many pipe smokers used Mason jars (also called canning jars and Ball jars), for example, to store their tobacco optimally, even though those jars, with a screw-cap, were in circulation as early as 1858. There are tobacco containers in this narrative that were called humidors—defined as airtight containers—but they were in name only, because they were not enclosures that were vacuum-sealed to keep the contents fresh, moist, or properly humidified. Understanding their history, two things are patently clear today: then, they were an unsuitable storage apparatus, and now they are popular collectibles.

I quote the opinion of four respected authors:

The English tobacco-boxes of the last century present but little variety of form. They were mostly circular or oval, nearly flat at top and bottom, and made of horn, papier-mâché, or japanned iron—the latter frequently having on the lid the simple device of a couple of pipes, in saltire, or, in a field sable. A few of the more wealthy class of smokers, such as elder brethren of the Trinity House, aldermen, country squires, and beneficed clergymen, sometimes indulged in the luxury of a silver tobacco-box (Joseph Fume [pseud.], A Paper:—Of Tobacco, 1839).

Tobacco when carried about the person for use, if not placed in a metal box, is held in a pouch or bag; both being generally formed of leather. German ladies think it no unfit employ to devote much time and attention in embroidering tobacco-bags for favored swains. …Gentlemen hang the tobacco-bag on the arm, as ladies used the reticule some time ago. The pouch is for the pocket, and is made of soft leather, frequently with the hair outside; a favourite substance for this purpose is moleskin, the thick soft down making it a mere pad in the pocket (F. W. Fairholt, Tobacco. Its History and Associations, 1859).

There is also a simple and ingenious tobacco-box used frequently in ale-houses, ‘which keeps its own account,’ with each smoker and acts also as a money box. It is kept on parlor tables for the use of all comers; but none can obtain a pipe-full, till the money is deposited through a hole in the lid. A penny dropped in, causes a bolt to unfasten, and allow smoker to help himself from a drawer full of tobacco. His honor is trusted so far as not to take more than his pipe-full, and he is reminded of it by a verse engraved on the lid:—‘The custom is, before you fill, ‘To put a penny in the till’ (E. R. Billings, Tobacco: Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture and Commerce… (1875). It was known as an honour box.

Indispensable to the pipe was the tobacco-box, now completely displaced by the rubber pouch. The boxes were made of metal, silver, iron, copper, brass and tin, and of ivory, mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, bone and wood, curiously and artistically carved (W. A. Penn, The Soverane Herbe. A History of Tobacco (1901).

According to Matthew Hilton (“Smoking and Sociability,” Smoke. A Global History of Smoking): Sherlock Holmes “…kept his tobacco in the toe-end of a Persian slipper…”

What did all those first- and second-generation tobacco boxes and jars look like? I’ll answer it this way. Borrowing from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem: “How do I love list thee? Let me count catalog the ways.”

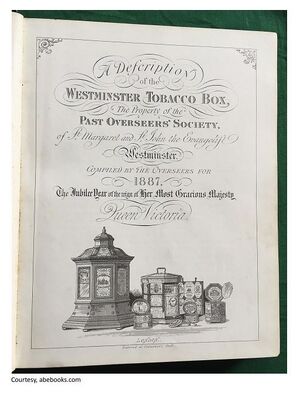

To begin, the Westminster tobacco box is the rarest and most ornate tobacco box ever produced. This image is from the frontispiece of A Description of the Westminster Tobacco Box, The Property of Past Overseers' Society, of St. Margaret and St. John the Evangelist Westminster. Complied by the Overseers for 1887, The Jubilee Year of the reign of her most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria (1887).

These two descriptions give you an idea of its components and what it looked like.

"The box itself and its surrounding cases have, however, been so loaded with engraved and pierced silver bands and plaques, many of considerable historic and artistic interest, that it is now probably the most valuable tobacco box in existence” (Charles R. Beard, “Base-metal Tobacco Jars in Mr. Reginald Myer’s Collection,” The Connoisseur, Vol. LXXVIII, May-August, 1927). "The original box, which is of horn, and which is said to have cost the donor fourpence, was left in 1713 by Mr. Henry Monck, to a kind of social club, consisting of persons who had either served as overseers of the above named parishes [Past Overseers’ Society of the united parishes of St. Margaret and St. John, Westminster] or who had paid the fine to be excused. In 1720 the society, out of respect to Mr. Monck, ornamented the lid with a silver rim; and in 1726 the box received a side-casing and bottom of silver. In 1740 the lid, within the rim, was further ornamented with an embossed border; subsequently the bottom was covered with an ‘ornamented emblem of charity’; and in 1746 a silver plate containing a portrait of the Duke of Cumberland, engraved by Hogarth, and an inscription, commemorative of the battle of Culloden, was placed on the inside of the lid. The last addition to the old box consists of a scroll on the outside of the lid, with the date 1765, enclosing a plate bearing the arms of the City of Westminster, and inscribed, ‘This Box to be delivered to every Sett of Overseers, on penalty of five guineas" (Joseph Fume [pseud.], A Paper:—Of Tobacco, 1839).

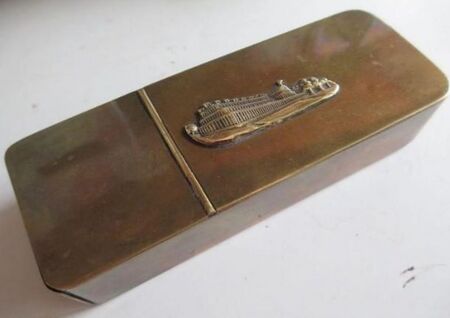

Here’s a tin-lined, brass tobacco box with three compartments, one for tobacco, one for matches and a striker, and one for a clay pipe. It was a souvenir made for the Great Exposition of 1851 in London.

An example of a late 17th-century Dutch tobacco box.

An engraved brass tobacco box from Germany from the same era.

Tobacco jars were designed to sit on a shelf, on a desk top, or in a cupboard. They included more decoration and a greater variety of shapes than the tobacco box. Early 17th-century examples were cylindrical, often with a domed lid and finial. Eighteenth-century tobacco jars were often in wood, especially lignum vitae, elegantly shaped, and frequently with a liner of pottery or tin. Many were shaped like apothecary jars.

A brief on tobacco jars from “Connoisseurship” (encyclopedia.com):

“Next came jars of faïence, that exquisite earthenware covered with a tin-enameled (stanniferous) glaze from French manufactories such as Mennecy and Sèvres. These were followed by, in approximate chronological order:

- various simple to highly decorative wood jars from Germany that were made in the early to mid-nineteenth century;

- molded figural jars in soft and hard paste from Bohemia made in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that depicted animals, children, and humans; and

- hollow cast bronze figural motifs produced, most probably, in France, and representing the last, the rarest, and the fewest produced in the past century.”

Many of the well-known ceramics factories made tobacco jars. They were a popular item for Royal Doulton, and Wedgwood made very attractive examples in black basalt and blue jasper.”

Essentially, jars could be plain, ornate, or figural. As an art form, size and weight were unimportant.

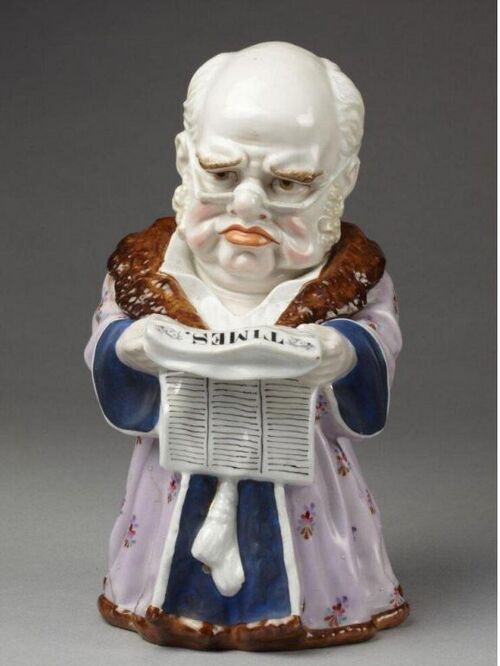

The most colorful, whimsical, and amusing tobacco jars were the figurals from several small factories in Bohemia, that westernmost region of what is now called the Czech Republic. Most were produced around the turn of the 20th century. Animals, human heads, historic figures and barrels were popular. The better ones had a recess in the cover that contained what was called a humidifier that, once soaked with water, released the optimal level of humidity for several days. Cookie jars assumed similar shapes in the time period; the clue is to look under the lid. By the 1930s, most potteries were making more formal and less colorful jars. The tobacco jars of the 1950s and 1960s were less ornate than earlier versions.

Here’s a figural tobacco jar from the Martin Brothers Pottery, London, a company that manufactured bird sculptures and bowls, vessels decorated with sea creatures, and tiles. The four brothers maintained the studio from 1873 to 1914. The Pottery manufactured a series of Wally Bird tobacco jars that do not represent an actual species—stylistically, they were considered grotesque owls or birds—that have a large, rather fierce-looking beak, massive feet and talons, and a quizzical look in their large eyes. Their heads lift off to reveal a cavity intended to store pipe tobacco.

The Robert A. Ellison Jr. collection of 140 works of art was a record-breaking auction for Rago Arts, Lambertsville, New Jersey, in February 2023. In it were many Martin Brothers works including this salt-glazed stoneware and ebonized wood Wally Bird tobacco jar dated to 1895. The estimate was $45,000–$60,000. The final bid was an insanely-astounding $100,800! In 2015, Phillips, New York, had sold a Martin bird tobacco jar modeled in the guise of Benjamin Disraeli for $190,000. That might have made sense considering who Disraeli was. But from what I know about tobacco jars, the Ellison bird will undoubtedly hold the record for many years as the priciest pipe-smoker’s accessory of all time!

These Delft tobacco jars were typically displayed in tobacco shops in the Netherlands two centuries ago.

Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795) was an English potter who founded his own company in 1759, and was known internationally for his earthenware and for his most important innovation, the colored, unglazed jasper that he produced in two-color ornamental wares, such as this tobacco jar.

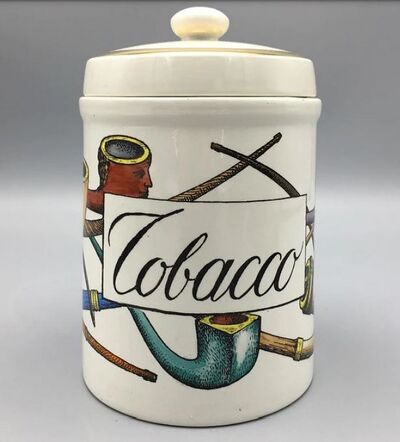

Piero Fornasetti (1913-1988) was an Italian multifaceted artist and designer who founded his company in Milan. It continues to produce porcelain and handmade decorative objects for the home that combine classical and surrealistic elements. This tobacco jar exhibits his modernist expression of tobacco pipes, circa 1950s.

Today, MacBaren, Savinelli, Dunhill and others offer their version of ceramic tobacco jars.

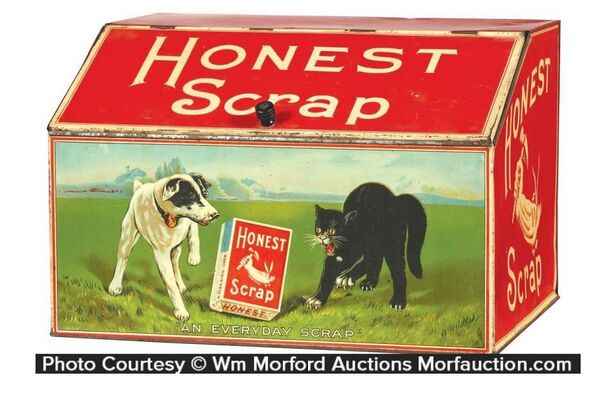

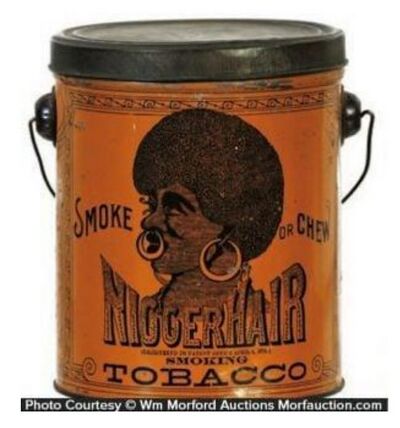

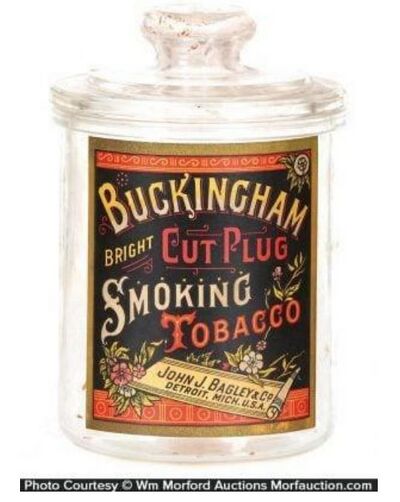

Starting in the late 1800s came bins designed for tobacco store display and bulk sales. So many brands, so many shapes, so many sizes!

From the bin to the lunch box.

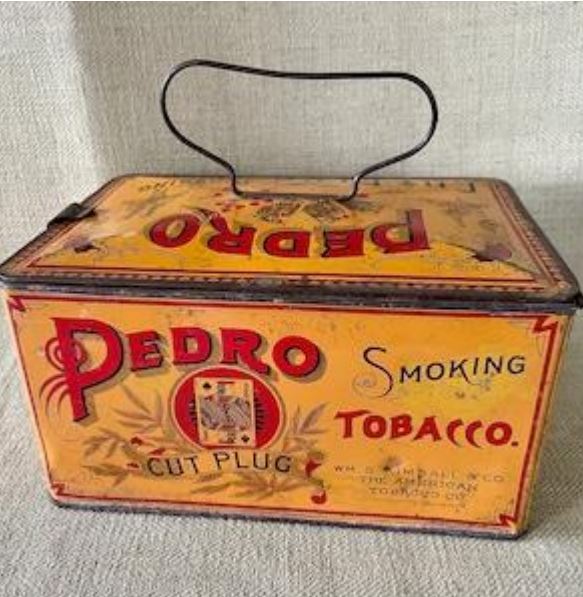

And from the lunch box to the tobacco pail.

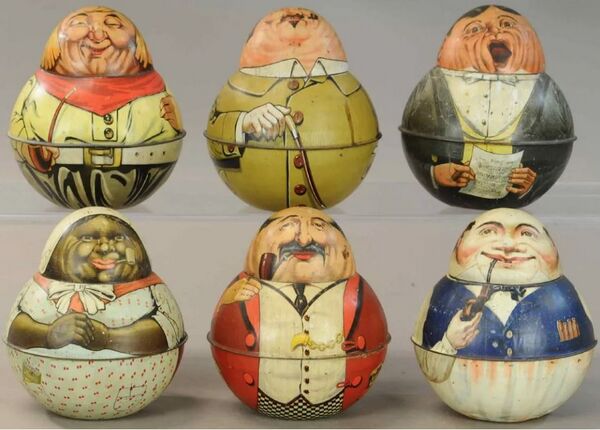

I had previously noted that the Westminster tobacco box was the most valuable of any that had been produced in the 1800s. This image illustrates what I believe to be the most famous, the most colorful, and the most sought-after tobacco tins, the Mayo Cut Plug Roly Poly figurals, manufactured in 1912, and issued by the American Tobacco Company. A name was assigned to each tin: Top row, left to right: Dutchman, Inspector from Scotland Yard, and Singing Waiter. Bottom row, left to right: Mammy, Satisfied Customer, and Storekeeper.

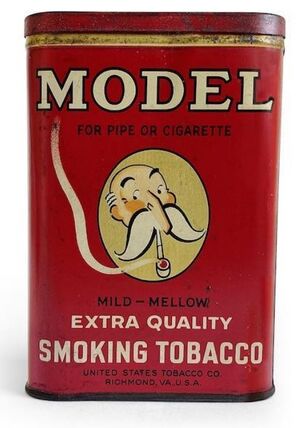

Upright pocket tobacco tins were designed to fit in the pocket of a suit-jacket, some of which were kidney-shaped. The ubiquitous pocket tobacco tin is the only metal container with a degree of standard styles and shapes. Would it surprise you to know that as early as the 1930s, Edgeworth ads read like this: “Smokers who are not acquainted with Edgeworth will find it in the famous blue tin at any tobacco shop anywhere. All sizes from the 15¢ pocket tin to the pound humidor package. Some sizes come in vacuum sealed (my emphasis) tins.” I’ve not been able to find a precise or an approximate date when production of this portable container ceased to be the standard, but I would estimate that it was probably in the late 1940s–early 1950s when they were replaced by cardboard and paper packages.

Want to see an assortment of pocket tins? Go to Gerardo’s Tobacciana Main Page (mygeradinc.com). In passing, some of these old tobacco tins have been repurposed by artist and filmmaker Lee C. Wallick. Read “The Artist Creating Miniature Worlds in Tobacco Tins” (anothermag.com).

Some tobacco companies also produced glass jars to promote their brands. Here is one example, and you can see an example of a glass cigar jar, “Classic and Clear: Glass Jars” at cigarjournal.com.

This glass tobacco jar is an example of what a pipe smoker might have had at home. It had a tight seal and served its purpose. This one has an attractive art-nouveau silver lid. This type could have also been used to store cigars.

Like most everything nowadays, the market is full of reproductions of tobacco boxes and jars, but that may only frustrate the serious collector of the genuine object.

Now what is familiar to every pipe smoker is the leather, canvas, and cloth roll-up or pipe roll, the tobacco pouch, and the more recent travel pipe bag that has an internal compartment for tobacco; each serves today’s pipe smoker adequately well. They are flexible, lightweight, and portable. They’re here to stay until something better comes along!

Three questions come to mind. Are these boxes, jars and tins expensive? The answer is intentionally somewhat vague: it depends on what you choose to collect. Are they easy to find? The Web is replete with sellers. Are they a worthy collectible? The Society of Tobacco Jar Collectors (tobaccojarsociety.com), founded in 1992 by Joe Horowitz, that has a global membership, believes so, considering the number of box and jar collectors around the world, I’d say “yes.” I’ll leave you with this thought: choosing a favorite tobacciana collectible may be the most challenging aspect of collecting anything related to smoking appurtenances and accouterments of the past. From the art to the accessories, selecting which items to collect is a difficult decision.

I close with additional information for the curious-minded. If your interest is piqued to see more boxes and jars, here are some places to look: 1stdibs.com; pipemuseum.nl; metmuseum.org; collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk; “Tobacco Jars” (ramshornstudio,com); “Vintage tobacco jars” (carters.com.au); “Antique Tobacco Jars” (sellingantiques.co.uk); “Antique Tobacco Boxes” (antiques-atlas.com); “Antique tobacco tins are smoking-hot collectibles” (liveautioneers.com); “Tobacco Tins & Jars” (pinterest.com); and “Tobacco Tins,” (antiqueadvertising.com). A group of “18th century Dutch tobacco boxes” is at the Rundale Palace Museum in Latvia (rundale.net). Thumb through William Bragge, Bibliotheca Nicotiana (1880) online and you’ll find descriptions of about 50 tobacco boxes, 30 tobacco jars, and 70 tobacco pouches. You can also watch a six-minute video of Dennis Rogers’ cigar and tobacco jar collection on YouTube.

And a few articles to read online: “The Dutch tobacco box” (pipemuseum.nl); “Antique Tobacco Jars” (collectorsweekly.com); “French Tobacco Jars” (crownandcolony.com); “Tobacco Jar” (kovels.com); “The Dutch Raid For Overseas Exotic Treasures, Such As Tobacco” (aronson.com); “Terra cotta jars in 1800s and 1900s held loose pipe tobacco” (heraldnet.com); “Tobacco Jars” (torquaypottery.info); Madeline Siefke Estill, “Colonial New England Silver Snuff, Tobacco, and Patch Boxes,” (colonialsociety.org); Charles R. Beard, “Tobacco Jars. Base-metal Tobacco Jars in Mr. Reginald Myer’s Collection” (The Connoisseur, 1927); Angela McShane, “The New World of Tobacco” (History Today, Vol. 67, Issue 4, April 2017); “Tobacciana Collectibles” (antiqueadvertisingexpert.com; “Tobacco & Smoking—Tobacco Boxes.” 18th Century Material Culture. Tobacco Boxes” (scribd.com); and Kim Wesseler (Johnson), “Do You Have Prince Albert in a Can?: A Chronology of Pocket Tobacco Tins (Dating Guide)” (academia.edu).

This rather substantial bibliography indicates that much has been published about all sorts of boxes, jars, and tins. As well, books on antique and contemporary advertising memorabilia usually contain one or more chapters on tobacco tins.

Anon. The Westminster Tobacco Box. A Description of the Westminster Tobacco Box, the Property of the Past Overseers' Society of St. Margaret and St. John the Evangelist, Westminster, Volumes 1-2 (1877) Batson, Steve. Country Store Counter Jars and Tins (1997) Bergevin, Al. Tobacco Tins and Their Prices (1986) ______. Drugstore Tins and Their Prices (1990) Carlson, Norman. Tobacco Containers from Canada, United States and the World (2002) Clark, Hyla M. The Tin Can Book. The Can as Collectible Art, Advertising Art & High Art (1977) Clemens, Kaye. Tobacco and Food Tins. A Price Guide (1973) Cole, Brian. Boxes. Collecting for Tomorrow (1976) Congdon-Martin. Tobacco Tins. A Collector’s Guide (1997) Crone, Ernst. Pieter Holm and His Tobacco Box (1953) Culme, John. British Silver Boxes, 1640–1840 (2015) Davis, Marvin & Helen. Collector’s Price Guide to Bottles, Tobacco Tins and Relics (1974) dePlas, Solange. Tabatières. Collection l’Amateur d’Art (1970) Dodge, Fred. Antique Tins. Identification & Values (1994) ______. Antique Tins. Identification & Values. Book II (1998) ______. Antique Tins. Identification & Values. Book III (1999) Dossmann, Ernst. Iserlohner Tabakdosen Erzählen (1981) Gage, Deborah and Madeleine Marsh, Tobacco Containers & Accessories. Their Place in Eighteenth Century European Social History (1988) Grandjean, Serge. Les Tabatières du Musée du Louvre (1981) Gregg, Thomas Tylston. Catalogue of a Collection of Brass Tobacco Boxes, 1760-1780, and Other Trophies Made to Celebrate the Battles in the Silesian and Seven Years’ War (1923) Griffith, David. Decorative Printed Tins. The Golden Age of Printed Tin Packaging (1979) Horowitz, Joseph. Figural Tobacco Jars. An Introduction and Illustrated Guide to Values (1994) ______. Figural Humidors. Mostly Victorian (1998) How, Harry. The Biggest Tobacco Box in the World (1894) Kirchner, Franklyn. Tobacco Pocket Tin Guide (1984) Könenkamp, Wolf-Dieter. Iserlohner Tabakdosen. Bilder einer Kriegszeit (1982) Layburn, John. Tobacco Tins and Other Things (1996) LeCorbeiller, Clare. Alte Tabakdosen Aus Europa Und Amerika (1966) Lewis, John Penny. A Mysterious Dutch Tobacco Box. Dutch Tobacco Boxes in Ceylon (1916) McPherson, Linda. Modern Collectible Tins (1997) Museum of Tobacco Art and History. Figural Tobacco Jars. Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Pottery and Porcelain Figurals (Sep 1992-Jan 1993) Myer, Reginald. Chats on Old English Tobacco Jars (1930) Nocq, Henry. Tabatières. Boîtes et Étuis. Orfèvreries de Paris XVIIIe et début du XIXe des Collections du Musée du Louvre (1930) Opie, Robert. Miller’s Advertising Tins. A Collector’s Guide (1999) Pettit, Ernest L. The Book of Collectible Tin Containers With Price Guide (1968) Snowman, Abraham Kenneth. Eighteen Century Gold Boxes of Europe (1990) Swedberg, Robert W. and Harriett. Tins ‘n’ Bins (1985) Winckworth, Peter. The Westminster Tobacco Box (1966) Zech, Heike. Gold Boxes. Masterpieces from †he Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection (2015) Zimmerman, David. The Encyclopedia of Advertising Tins. Smalls & Samples (1994) ______. Encyclopedia of Advertising Tins. Smalls & Samples, Vol. 2 (1999)