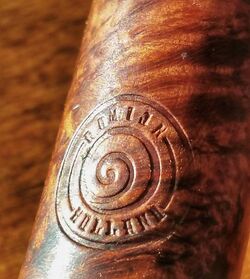

Martin Romijn

Martin Romijn (b. 1969; pronounced “Romine”) is a Dutch artisan based in the city of Leerdam, in the Utrecht province of the Netherlands.

Biography

Romijn took up pipe smoking around the age of 20, but it would be many more years before he made pipes of his own. Instead, like the German artisan Frank Axmacher, he spent the bulk of adult life with a working in a different medium: stone. Romijn had joined the Dutch Marine Corps after leaving school and, upon returning to dry land, found that he wanted a job doing something with his hands. This led to him training as a stonemason and stonecutter, which served as his primary vocation for the next 30 years. Romijn’s services in this vein would be enlisted for a variety of needs, from tombstones to high-end interior stoneware (Levine, 2019).

As the years went by Romijn developed a degenerative condition affecting his legs, meaning that his mobility, along with his ability to meet the significant physical demands of his job, was drastically diminished. But by this point, Romijn had found that many of the skills he'd developed over the course of his career could be redirected towards another practical pursuit in the production of tobacco pipes. Such a move is far from unprecedented in artisan pipe making, whose history is replete with former carpenters, sculptors, and even painters; neither is such a move being encouraged, in part, by grievous misfortune, as in the case of Manfred Hortig, or even Bo Nordh.

Before turning to Romijn’s pipes, it should be noted that these were not the first “pipe products” that he had made. A frequent visitor to early online pipe forums, such as alt.smokers.pipes, Romijn had been hooked not only by the various artisan-made pipes shared and sold by other users, but also by the accessories made by a growing number of talented individuals (Van Goor, 2013). These included the popular Ming Kahuna tampers handcrafted by Art Ruppelt, of which Romijn was a great admirer. Inspired by Ruppelt and others, Romijn started making his own accessories in the early 2000s. Though he was still a full-time stoneworker at this point, Romijn discovered a considerable audience for the accessories that he had created in that same medium. Not only did these accessories provide Romijn with a supplementary income, but also with something he could trade for tobacco blends not available in the Netherlands, such as his beloved Embarcadero, manufactured by America's Cornell & Diehl.

By the time his health issues began to affect his job, Romijn had already been selling his handcrafted pipe accessories on the side for nearly a decade. These included tampers, ashtrays, and magnetic and floating pipe stands, carved from materials such as marble, granite, and sedimentary rocks containing fossilised marine life. A reduction in his day-to-day working hours meant he had more time to experiment in his home workshop. One thing led to another, and Romijn was soon exploring forms of freehand briar carving, with a view to making tobacco pipes.

Romijn’s pipe-making career properly began in 2016 and, aside from occasional guidance from his good friend and travelling companion, Dirk Heinemann, Romijn can be described as self-taught. On the other hand, Romijn can also be described as someone with a more formal training, if we count his stoneworking education. This notion is not unreasonable, and not only because of their common, subtractive, element. While there is a long history within briar cutting and pipe-making of “reading the grain” as a heuristic for optimal selection and shaping, similar ideas have existed within stone sculpture for far longer. Romijn does indeed “read” the grain as he makes a pipe, as he explains in a 2019 interview:

“Every block has its own story. How does the grain go, what can you expect when you cut it in a certain angle etc. It can be that I have had the briar piece in my hands dozens of times before I know which pipe it hides. And even then, sometimes the wood has its own plan. When I come across a sandpit or another irregularity I have to adjust my plan to fit the briar. In such a case I always say that the briar speaks to me and that I should listen. This way you often get the most surprising and beautiful results.” (Van Goor, 2019)

Yet, as one finds in a much earlier interview with Romijn on the topic of his accessories, conducted years before he had considered making pipes, much the same ethos is already at work:

I select pieces of stone based on their structure. Pieces with a special pattern or present fossils I lay aside. When I look at certain stones I already see a shape or I get an idea. But most of the times the piece develops from out of the stone [it]self when I am working on it. I let the stone inspire me, in fact I “unwrap” the piece I am working on. It is already hidden in the stone.” (Van Goor, 2013)

It should come as no surprise that Romijn is a great admirer of the Danish masters. Nor should it that he holds former Preben Holm protégé Poul Winsløw in the highest regard. Yet Romijn’s ethos—consonant as it is with that of the Danish “fancy” movement—nevertheless originated as a transposition of experiences beyond Danish pipes and beyond briar in general.

Despite their similarities, stone and wood are still very different materials and mediums. Therefore, as with any budding pipe-maker, Romijn had to become accustomed to working with briar root on its own terms. Some of his first forays in this regard were, depending on who one asks, acts of minor sacrifice and/or well-intentioned sacrilege. Using some of his personal pipes as test subjects, including an old Vauen, Romijn set about re-working the finished stummels to see what else might be “wrapped” inside. Pleased with the results, Romijn set about acquiring briar blocks so that he could create something that was truly his own, with the first few being generously donated by Belgian artisan Nick Ramaekers (Massis Pipes). Despite a few rough starts, through online resources and sheer perseverance, Romijn arrived at a point where he could make a pipe from scratch. Furthermore, he was soon able to make a pipe that other smokers wanted to buy. His first customers were his friends; the next were users of the Anglophone, Dutch, and Belgian pipe forums that Romijn frequented. Romijn’s pipes would later be picked up by Amsterdam’s oldest tobacconist, P.G.C Hajenius.

As the common refrain goes, Romijn’s techniques and style have come a long way since the early years of his pipe-making career, but the tools he employs have remained largely unchanged. In his workshop one finds a fairly typical array of equipment used in artisan crafts, including a band saw, a belt sander, a buffing wheel, and various hand tools. Less typical is Romijn’s preference for his wood lathe over a metal lathe. Whether one or the other is “better” for making pipes, along with the advantages each offers, is the subject of a recurring debate within the artisan pipe-making community, though metal lathes are the more popular choice. With that said, one finds many ardent defenders of the wood lathe in the contemporary high-grades scene. For Romijn, what defines the wood lathe relative to the alternative is the sheer amount of freedom it allows him during bowl turning, a perspective shared by fellow proponents. On the other hand, there is also a sentimental aspect to Romijn's lathe, being as it was a gift and a gesture of encouragement from his parents at the very beginnings of his pipe-making enterprise. As such, it has remained central to his craft ever since.

As for style, Romijn describes his work as geared towards more “organic” shapes. He believes such shapes allow one to faithfully represent the unique patterning of each briar block, while also creating something that will feel comfortable in the smoker’s hand. Strawberries, eggs, apples, and acorns abound in Romijn’s portfolio, alongside broad-bowled Dublins and brandies of the Scandinavian ilk.

From an outside perspective, Romijn’s designs could be described as “bowl forward.” Not in the sense that they are canted (though they often are) and not in the sense that their shanks and stems are neglected. Instead, and not unlike the pipes of, for example Roman “Doc” Kovalev or Piero Vitale, Romijn combines a naturalistic approach to shaping with a playful subversion of the unwritten rules pipe making as regards proportion. As such, Romijn's bowls embody a distinct fullness in relation to the rest of the pipe, conferring a sense of gravity and momentum to the overall design.

Today, Romijn’s career as a stoneworker is at its end, with his career as a pipe-maker taking up the bulk of his time and energy. Nonetheless, something of Romijn the stoneworker persists in the habits and the mentality of Romijn the pipe-maker:

“I quite often jokingly tell people who ask me about how I decide what pipe to make; the pipe is already inside the piece of briar, I only have to reveal it by taking away everything that doesn't look like a pipe!” (Personal correspondence, 2024)

Gallery

Contact Information

Website: http://www.romijnpipes.nl/ Email: mart.romijn@gmail.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/romijntampers

References

- Levine, B. (2019, October 28). Martin Romijn Interview. Pipes Magazine Radio Show (No. 372) [Audio podcast] https://pipesmagazine.com/blog/radio-talk-show/pipes-magazine-radio-show-episode-372/

- Van Goor, A. (2013). Stonecutter’s story. Dutch Pipe Smoker, October 28 [Blog]. https://dutchpipesmoker.com/2013/10/28/stonecutters-story/

- Van Goor, A. (2019). The briar listener: Romijn Pipes. Dutch Pipe Smoker, July 9 [Blog]. https://dutchpipesmoker.com/2019/07/09/the-briar-listener-romijn-pipes

- Personal Correspondence, 2024. Here Romijn alludes to a quote attributed to Michelangelo, which goes, “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.”