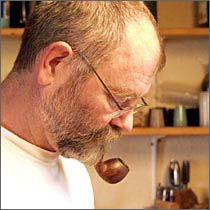

Ivarsson, Lars

We are very saddened to learn that Lars died after a long battle with cancer on February 11th, 2018. The following tribute is courtesy of Smokingpipes.com

Passing of a Giant February 12, 2018 by Sykes Wilford

A dozen years ago, late summer in 2006, I visited Lars Ivarsson for the first time. We'd met and spoken on a few occasions, but that day we spent hours together, in his workshop, over a fantastic lunch that he and his wife Annette cooked, just talking quietly, smoking our pipes as we looked out from his garden over the fjord that made his home one of the most beautiful places on earth. He spoke at length, but mostly about travel, economics, politics and other topics unrelated to pipes and pipemaking. But his pipes spoke for him.

I was nervous. So terribly nervous. I was young, in my mid-twenties. And Lars, in his sixties and at the apex of his career, was the most influential living pipemaker, a daunting figure in the craft and the hobby. More than that, Lars carried himself with gravitas. Not that he did not take joy in his work, his family, his life, but he took his work — and his other endeavors — seriously: it manifested in his perfectionism, his vision for not just what was, but what could be. Before that day, I respected Lars as a pipemaker. That day, he earned my respect as a man and a human being.

A genius as a pipemaker, he was learned and talented in a variety of fields, erudite in at least four languages, and passable in a couple of others. He was clever and self-assured, with much to prove to himself and little to prove to others. He rarely spoke of other pipemakers, except to tell the occasional story of Sixten's workshop in the 1960s and 1970s. And, of course, to express the tremendous pride he felt for his daughter Nanna and her pipemaking.

Lars passed away yesterday, February 11th, 2018, following a prolonged battle with cancer. He was 73 years old. To earn pocket money, he began working in his father's workshop at age eight, with no realization that those early days of sweeping floors and odd jobs would launch a career spanning more than six decades and carve indelible chapters into the foundation and history of pipemaking.

Lars' importance to pipemaking cannot be overstated. If his father Sixten invented the idea and methods of the modern artisan pipe, Lars refined the techniques and methods and pushed the aesthetic in a bold new direction. The current generation of pipemakers, those in their thirties and forties, lean heavily on his shaping lexicon. Consciously or not, they use processes and methods that he invented or refined. Sometimes this influence is obvious: The teardrop shaped shank, for example, has become a common theme in artisan pipes in the past decade. Sometimes, it's subtle: Tiny but essential stylistic elements, from the curvature of the shank to the rounding of the rim, are dependent on Lars' ideas. His quest for perfection was manifest in his continuous refinement of details — ideals that continue to affect pipemaking worldwide, and will undoubtedly continue to do so for generations not yet born.

Lars completed a degree in business from Copenhagen University in 1969, but his career was pipemaking. And his great love was pipe design and shapes. Lars once told me that he made shapes iteratively, chasing a concept, inching closer to that ideal over time, but that if he ever achieved it, he'd not be able to make that shape again. Acutely aware of the irony, Lars was certain that perfection would render a shape done for him. Perfection, having been reached, precluded further work toward that ideal. He never, in his mind at least, achieved that perfection. There was always scope for slight improvement, even after sixty-plus years of honing his craft, even having made some of the most perfect pipes the world had seen.

Lars Ivarsson is survived by his wife, Annette, as well as his daughters, Nanna and Camilla, four grandchildren, and by a body of work and an inventiveness that will continue influencing the world of pipes for as long as tobacco is smoked in briar.

This is an excerpt from Chapter 7 of the book, In Search of Pipe Dreams. Copyright 2003 by Rick Newcombe. All rights are reserved by the author. (Edited for content)

Ivarsson pipes were available in the United States in the 1960s and 70s through Iwan Ries and Co. in Chicago. Once or twice each year Stan Levy, the store's owner, visited Sixten and Lars Ivarsson in Copenhagen and bought a handful of pipes that he sold in America.

I met the 90-year-old Stan at the Chicago Pipe Club show last spring, and I asked him why his store no longer sold Ivarsson pipes. He said the Japanese started offering even higher prices and he just couldn't compete.

Since then, Ivarsson pipes have simply not been available to American collectors. Of course, there is always the occasional Ivarsson pipe that might pop up at a pipe show or a garage sale, but finding them has been like looking for a needle in a haystack. Two American collectors have owned several dozen over the years: Rob Cooper, who lives in the Philadelphia area, and Ron Colter, who lives in the Washington, D.C. area. There may be others as well, but they are all the exception.

Ivarsson pipes have been largely unknown to American collectors. For example, there is hardly a mention of Ivarsson in Richard Carleton Hacker's otherwise excellent work, The Ultimate Pipe Book. There is not a single mention of Ivarsson in The Pipe Smokers Ephemeris: Book I, which covers the subject of pipes from the years 1964 - 79. Also -- neither book gives credit to Jess Chonowitsch, considered by Nikos Levin and many other collectors to be the greatest pipe maker in the world today.

But in Europe, the story is totally different. The Illustrated History of the Pipe, which was written by Alexis Liebaert and Alain Maya of France, gives the Ivarssons the credit they deserve. Sixten is called the greatest pipe maker of the 20th century. And as good as Sixten was, many collectors believe that the only pipe makers to equal or even surpass his skill are Jess Chonowitsch, Bo Nordh and Sixten's son, Lars. Other collectors believe the S. Bang pipes are the best in the world. My own opinion is that all four are fantastic, and calling one better than another is highly subjective.

Lars makes about 70 pipes per year, and he sells them for between $1,000 and $2,000 each -- some for a little less and a few for a lot more.

Lars is 51 (in 1996 - red.), and he started making pipes 40 years ago. As a child, he liked to hang around his father's workshop. "Once I turned 12, my allowance was cut off," he said. "I had to earn the money I got by helping with the pipes."

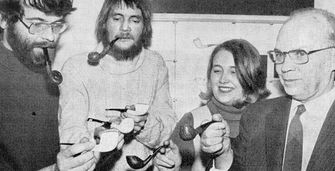

Lars remembers when Bo Nordh (now deceased - ed.), an engineering student from Sweden, first visited Sixten and Lars in Copenhagen to study their pipe making techniques. They are still good friends today. He also remembers when Jess Chonowitsch worked in the Ivarsson workshop. The pipes are stamped with a circle that reads, "An Ivarsson Product." Many also include the year and the number made that year. For instance, 24/1970 stands for the 24th pipe made in 1970. Lars' pipes have an "L" stamped on them, while Sixten's have a sunshine.

Lars said that besides Sixten, he and Jess were the only pipe makers allowed to make pipes that were stamped "An Ivarsson Product." He remembers being in his 20's when the three pipe makers -- Sixten, Lars and Jess -- would work all day making pipes at the workshop in downtown Copenhagen. They had a storefront window, and many of the locals would wave or stop by for a chat.

I first met Lars in Copenhagen in August 1995. He told me that he had never been to the United States, even though he had traveled all over the world many times. His English was easy to understand. "I had to learn English early in order to negotiate on behalf of my father," he said.

So I invited Lars to stay at my house in Los Angeles if he ever decided to visit America. You can imagine my excitement, then, 11 months later when I met Lars at L.A.'s airport. He had traveled nearly 24 hours and was eager for a pipe, but otherwise in good shape.

Lars, Dayton Matlock, editor and publisher of Pipes and Tobacco, and I visited Jim Benjamin in San Diego. Jim is an expert at restoring old pipes, and he thoroughly cleaned the inside of one of Lars' pipes.

When we were in Jim Benjamin's workshop I asked Lars if he would mind smoothing out the plateau top of a large free hand pipe that had been made by another pipe maker. It was amazing to watch him work, first with a sanding wheel and then with one of his handmade knives. Jim Benjamin said he'd be afraid to work with a knife. He was speaking for Dayton and me as well. But Lars took the knife to his beard, cupped his hand under his beard, and shaved off a handful of whiskers. "As long as the knife is sharp," he said, "there will be no problem."

I asked him about the age of briar, and Lars said there is a lot of misinformation on the subject. He said that most of the time he can tell the age of the briar by looking at a pipe. The range seems to be anywhere from five years to -- at the outside -- 50 years. He said the myth of hundred-year-old briar is just that -- a myth. He said that some of the wood he works with has been stored since the 1950s, but he said that's the exception. Most of the briarwood that he uses has been stored for between one and five years. As long as it is good briar, and thoroughly dry, it does not have to be so old to have good smoking qualities. In fact, Lars said, if the briarwood is too old it becomes difficult to work with.

"We also use the highest quality vulcanite, which we buy from Germany. All of our mouthpieces are hand-cut. As important as the materials are, however, the way the pipe is made is most important. A good pipe is 90 percent physics, 5 percent materials and 5 percent magic."

The "magic" that Lars referred to is a reflection of the pipe maker's passion, artistry and intuitive feel for how a particular pipe should be made. A great pipe is one that draws smoothly and stays lit easily and does not require a lot of tinkering, poking, tamping and relighting.

Lars offered insights into how briar colors after repeated smoking. I told him my favorite was briar that turned a dark reddish-brown over time. He said that wood only turns red because of an initial stain of red by the pipe maker. The wood itself darkens into brown or a grayish brown color, but if the pipe were given an early stain that included some red in it, the pipe will look plum-colored over time. Without that red stain, however, it won't.

He does all his own sandblasting at home in a furnace he bought just for that purpose.

Lars has always preferred to live and work in the country. In fact, he and his wife recently purchased a new home on the sea that is 100 kilometers from downtown Copenhagen. He says the house needs a lot of work, which he will do himself. He plans to set up his pipe making workshop adjacent to the house. "I'm just a country boy," he likes to say.

Back at my house I showed Lars and Jess several of the pipes in my collection that looked beautiful but did not smoke well. In each case, they examined the pipe in the same way that you might expect Sherlock Holmes to examine an important piece of evidence. First they turned it this way, then that way -- with the mouthpiece and then without the mouthpiece. They never hesitated to blow through the pipe to listen to how the air flow sounded. "We need to avoid having the mouthpiece sound like a clarinet," Lars said at one point. In each case, they showed me the flaw.

Nanna is Lars' youngest of two daughters and the one person he regards as his logical successor in the future. She is 22 and already an experienced pipe maker. Nanna was recently accepted at a design school that rejected 488 of the 500 students who applied. She will continue making pipes under her father's guidance while studying design. She told me that she wants to use her study of design to create new shapes for pipes.

It is remarkable how many designs are considered commonplace today but were revolutionary at the time that Sixten or Lars or Jess introduced them. For instance, I mentioned to Lars that the egg is one of my favorite shapes. I asked if the Ivarssons had anything to do with it. "Yes," he replied. "My father created it."

During the 40 years in which he has made pipes, Lars has stamped a fish on 35 of them, and Jess has stamped a bird on approximately the same number. The fish and the bird are reserved for those pipes that are absolutely perfect in every respect.

When we were at the outdoor banquet dinner of the West Coast Pipe and Cigar Expo, I was smoking a Sixten Ivarsson pipe made in 1970. Shortly before dinner was served, I put the pipe down on the table and excused myself. I walked 50 or so yards to get to the lobby, asked directions to the men's room, went to the bathroom and washed my hands, then found the telephones and made two quick phone calls. I walked the 50 yards back to the table and sat down at my place. I was gone at least five minutes and perhaps as many as 10. I picked up the Ivarsson pipe I had been smoking, put it in my mouth and puffed. Unbelievably, it was still lit! I showed this to Lars and Jess, and Lars made a joke that it was a good way to waste tobacco. In truth, hardly any tobacco had burned -- just enough to allow the pipe to smolder. I told him this was incredible. I had never seen anything like it. Still not wanting to take any credit, they both said the outdoor breeze contributed to the pipe staying lit. No doubt, I said, but not for five to 10 minutes. Determined, I asked once more, "How can you explain this?"

Lars looked serious at first and then smiled as he answered, "I guess it stayed lit because of that final 5 percent -- what Sixten calls magic. It's the magic of knowing how to make the perfect pipe."